One of the most-hyped features of Apple's new iPhone 6s is 3D Touch, which senses how hard you're pressing the touchscreen to perform different functions. It's a first for smartphones, but it's still just a hard, featureless surface, and makes typing and precise onscreen control just as tricky as ever.

But what if touchscreens could be malleable, alternating between both firmness and softness to help guide your fingers as effectively as actual physical buttons? That's the thinking behind GelTouch, a thin gel-based layer that can transition between soft and stiff to provide a range of different tactile feedback responses to the user.

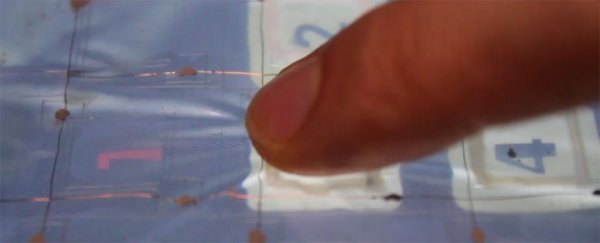

Developed by German researchers at the Technical University of Berlin, the system uses a 2-mm-thick layer of flexible and transparent 'smart gel' that's completely soft when inactive. Once the gel is activated by raising its temperature, it hardens into an opaque, plastic-looking substance that's 25 times stiffer than the unactivated gel.

The researchers say the temporarily activated areas can be morphed freely and continuously and are not constrained to fixed shapes on the screen. The idea is that you could enhance user control of touchscreens with panels augmented by the gel layer, as virtual elements like onscreen buttons, sliders, or other sorts of control mechanisms could actually have a tactile feel to them via the activated gel.

"You basically can have unlimited shapes or structures or whatever you want," Viktor Miruchna, lead author of the paper describing GelTouch, told Rachel Metz at the MIT Technology Review.

Typing is one area where the technology could be of great assistance, as lots of us – albeit maybe not millennials raised on touch devices – find it difficult to type reliably with any kind of speed on virtual keyboards (plus you need to keep your eyes glued to the screen, unlike touch typing on physical keyboards).

Another area where the gel could come in handy is gaming, as virtual joysticks and buttons are the bane of many a mobile gamer's existence (myself included).

According to the researchers' testing, the majority of users who sampled a GelTouch prototype device got the hang of it, with almost 95 percent of them indicating that they could detect tactile features reliably.

If there's one limitation with the gel interface, it's the heating system used to switch the gel between hard and soft. The gel in the prototype needs to be heated above 32 degrees Celsius to become tactile, and transitions between firm and soft take a couple of seconds to take effect. Still, if these wrinkles can be ironed out – which the researchers involved are intending to do – smart gels could make for amazing new kinds of interfaces in the near future.