Are you a morning person or a night owl? The answer may be written in your DNA. A study of nearly 90,000 people who had their genomes sequenced by the consumer genetics company 23andMe has identified 15 versions of genes that are linked to reports of being an early or a late riser.

The findings, which were published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, could improve our understanding of how our bodily clocks work – both in healthy people and in those of us with sleep disorders.

Bodily clocks

Most living things, including people, live by natural 24-hour cycles called circadian rhythms. These internal 'clocks' determine whether you have a preference for waking up early or staying up late – something scientists call your chronotype.

Previous studies have found genes that may be linked to circadian rhythms in animals, but until now, there's hasn't been much research on how these genes determine preference for being an early or a late riser in people.

UCLA/Horvath Lab

UCLA/Horvath Lab

In this study, 23andMe's principal researcher David Hinds and his colleagues have done what's called a genome-wide association study (GWAS), where they looked at many different versions, or variants, of a gene to determine if any of them were linked to a specific trait – in this case, being a morning or evening person.

They studied a group of more than 89,283 people who submitted their DNA to 23andMe via spit samples – the standard way 23andMe runs its tests. The participants also filled out two online surveys that asked whether they considered themselves a morning person or a night owl.

Of the more than 135,000 people who answered at least one survey, 75.5 percent fell into the category of morning or night persons. The researchers didn't include people who said they had no preference, or people who gave different answers on the two surveys.

Morning people vs. night owls

Of the 15 genetic variants the study found that were linked to being a morning person, seven of them were near genes that are known to play a role in circadian rhythms. And some of these genes were also near ones involved in sensing light from our eyes. The close proximity of these genes suggests they are likely to have related functions – specifically, telling us when to be awake.

The findings revealed all sorts of interesting patterns. For example, more women (48.4 percent) than men (39.7 percent) said they were morning people. And people over 60 (63.1 percent) were much more likely to prefer mornings than people under 30 (24.2 percent), which fits with previous research that found older people tend to rise earlier.

But that's not all. Compared with morning people, people who self-identified as night owls (while not a truly objective measure) were almost twice as likely to suffer from insomnia and about two-thirds as likely to have been diagnosed with sleep apnea, a sleep disorder that causes you to repeatedly stop breathing while you sleep. By contrast, self-described morning people were less likely to need more than eight hours of sleep, to sleep soundly, to sweat while sleeping, or to sleep walk.

The scientists also noted that people who identified as morning people tended to have a lower body mass index (BMI) than night owls, but they weren't able to show that one caused the other. However, there was one gene they found to be more common in evening people, known as the FTO gene, which has been linked to obesity.

The self-reported night owls in the study were also more likely to have depression, but again, the researchers couldn't show that being a night owl causes depression or vice versa.

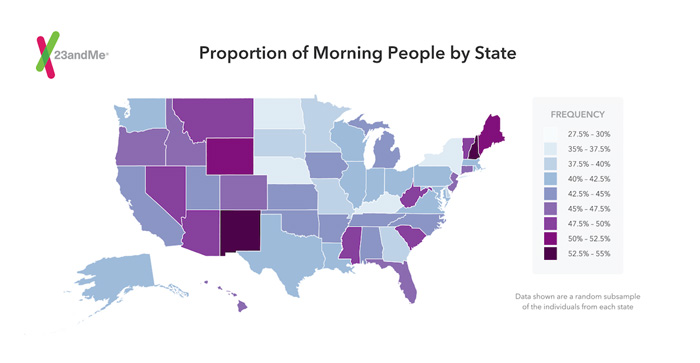

Here's a map based on a random sample of people who agreed to take part in 23andMe's research, which shows the percentage of early risers in every state. Looks like most of the early birds are New Mexico and New Hampshire, while the night owls are in New York (not surprisingly), Kentucky, North Dakota, and Nebraska:

23andMe

23andMe

The limits of self-reporting

The study had one important limitation, however – it was based on people's answers to a single question ("Are you a morning or an evening person?"), instead of more objective scientific questionnaires, Roland Brandstaetter, a biologist who studies sleep cycles at the University of Birmingham in the UK and was not involved in the study, told Business Insider.

Simply asking someone if they're a morning person may not lead to an accurate answer. For example, "If you ask individuals whether they are morning people or evening people, a late-type who is forced into an early schedule by work may regard themselves as a morning type," Brandstaetter said.

Also, the researchers didn't include data on people who are somewhere in between a morning person and a night owl, which may make up close to half of all people, he added. Hinds admitted that the study's survey method "might modestly reduce the power of the study," but that this "should not materially bias the findings or lead to false results".

Hinds added that simple questions "can be very effective for genetic studies, where the most important consideration for study power is the [number of participants]".

Of course, genetics isn't the only factor that determines when you wake up. Societal pressures like work and family life also play important roles.

Next, 23andMe plans to combine its data with that of a research charity called UK BioBank, to look for even stronger genetic patterns.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: