Around 500 million years ago, during the Cambrian period, Earth was undergoing some massive changes – organisms were becoming more complex, and animals were becoming more abundant.

Some looked relatively normal, and some had faces that looked like butts with claws.

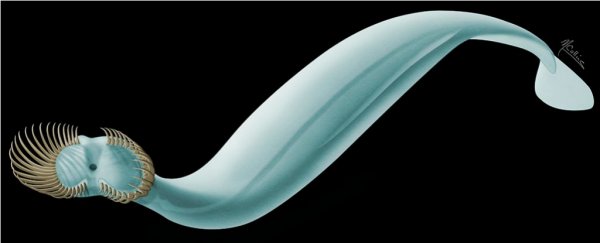

A new study has just been published identifying this weird creature as a 10 centimetre (4 inch) worm called a chaetognath – a small, swimming marine carnivore.

"Darting from the water depths, the spines would have been a terrifying sight to many of the smallest marine creatures that lived during that time," says one of the researchers, Jean-Bernard Caron, from the Royal Ontario Museum.

"This new species was well adapted to capturing prey with the numerous, claw-like spines surrounding its mouth."

Before we explain more about this creature, please enjoy this terrifying video of what researchers think it would have looked and behaved like.

Now we've got that out of the way, the worm, named Capinatator praetermissus, had about 50 spines on its head, which would push any food that comes near it into its, frankly, anus-looking mouth hole.

Although you might think that a 500-million-year-old weird worm isn't that important in the evolutionary scheme of things, that is definitely not the case.

"This is the most significant fossil discovery of this group of animals yet made," says one of the researchers, Derek Briggs from Yale University.

So why is it so important? Well, this new species is thought to be a forerunner of the much smaller chaetognaths swimming around in today's oceans.

These little guys make up a large portion of the world's plankton – making them a pretty big deal in the food chain.

But the amount of spines are also completely different to today's chaetognaths – C. praetermissus's 50 spines are nearly double the maximum number that current chaetognaths use to catch their prey.

The other cool thing about this research is the fossils themselves. The team had to use over 50 specimens to come to a conclusion about the species, because fossils of the worms' squishy bodies are extremely rare finds.

J.B. Caron/Royal Ontario Museum

J.B. Caron/Royal Ontario Museum

"The [fossilised] specimens preserve evidence of features such as the gut and muscles, which normally decay away, as well as the more decay-resistant grasping spines," says Briggs.

"They show that chaetognath predators evolved during the explosion of marine diversity during the Cambrian Period, and were an important component of some of the earliest marine ecosystems."

So there you go – even if you look like a butt with claws, you can totally still be important in the history of Earth.

The research was published in Cell Biology.