The fruit of Africa's marble berry (Pollia condensata) is a true living gemstone, sporting a stunning metallic blue sheen that never fades.

Only the berries aren't actually blue in the sense most of us might assume. At least, they don't contain any blue pigment. The cool hue is the result of a brilliant optical illusion, which only becomes apparent when you take a very close look at the cells of the fruit under a microscope.

That's exactly what a team led by researchers from the University of Cambridge in the UK did to discover how this marble-like berry gets its special appearance.

Related: Scientists Recreate Rare Pigment Behind Octopus 'Superpowers'

Our world of color is typically the result of subtractive coloring. Materials absorb mixes of wavelengths present in white light; what remains contributes to the object's color.

The fruit employs a structural color trick, where fibers on the outer cell walls are arranged in a special twisting structure that causes waves to interfere with each other.

This layered approach means some waves cancel out, and others grow, creating a unique iridescence in select parts of the spectrum. In this specific case, wavelengths of blue light predominantly survive.

"The bright blue coloration of this fruit is more intense than that of many previously described biological materials," write the researchers.

"This is the highest reported reflectivity of any land-based biological organism, including beetle exoskeleton, bird feathers, and the famously intense blue of Morpho butterfly scales."

There are plenty of examples of structural color in nature, but it's not often seen in fruits. A related trick can be seen in the fruit of the Elaeocarpus angustifolius tree, although it is less shiny.

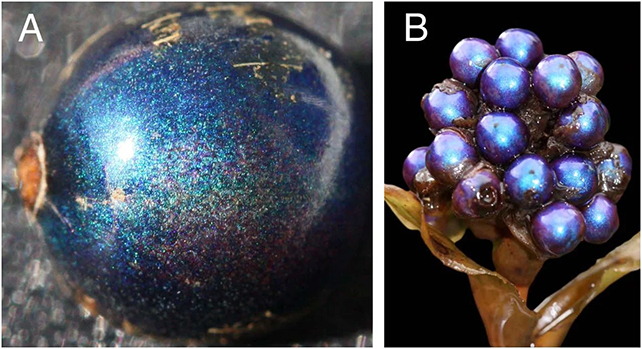

Compared with the light reflecting from a silver mirror, the marble berry reflects 30 percent of the light that hits it, which is unusually high. And while the twisted fiber layering means blue light dominates, some other colors are mixed in too, for a slightly pixelated final look.

"Our investigation demonstrates that variation in multilayer thickness in the Pollia fruits provides an optical response that is apparently unique in nature," write the researchers.

"While blue reflectance is dominant, the sparse distribution of green and red reflecting cells gives the fruit an intriguing pixellated (pointillist) appearance, not recorded in any other organism."

There is a point to all this show, the researchers suggest: by attracting birds with its striking appearance, the P. condensata fruit can ensure wider dispersion for its seeds and its continued survival.

Because of the way its cells are structured, the fruit can hang on to its good looks for decades.

Since there's no nutritional value to the berry, the seed-carrying fruit has to rely on standing out visually.

Peacock feathers use a similar kind of technique to catch the eye, although here a different structural color approach is used, in combination with pigments.

Once again, millions of years of evolution have fine-tuned nature in a way that's deeply impressive – even before you know the trick behind it. We're still playing catch-up when it comes to developing colors and materials of our own.

"This obscure little plant has hit on a fantastic way of making an irresistible shiny, sparkly, multi-colored, iridescent signal to every bird in the vicinity, without wasting any of its precious photosynthetic reserves on bird food," says Beverley Glover, a plant scientist at the University of Cambridge.

The research has been published in PNAS.