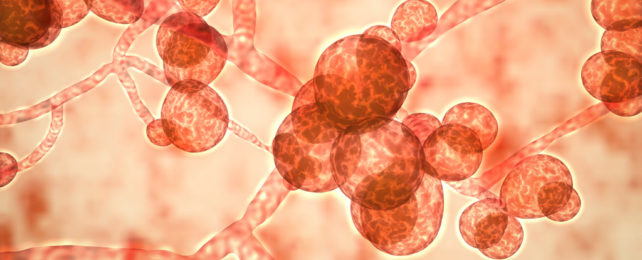

Scientists discovered traces of fungi lurking in the tumors of people with different types of cancer, including breast, colon, pancreatic, and lung cancers.

However, it's still not clear that these fungi play any role in the development or progression of cancer.

Two new studies, both published Sept. 29 in the journal Cell, uncovered DNA from fungal cells hiding out in tumors throughout the body.

In one study, researchers dusted for the genetic fingerprints of fungi in 35 different cancer types by examining more than 17,000 tissue, blood, and plasma samples from cancer patients.

Not every single tumor tissue sample tested positive for fungus, but overall, the team did find fungi in all 35 cancer types assessed.

"Some tumors had no fungi at all, and some had a huge amount of fungi," co-senior author Ravid Straussman, a cancer biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, told STAT; often, though, when tumors contained fungi they did so in "low abundances," the team noted in their report.

Based on the amount of fungal DNA his team uncovered, Straussman estimated that some tumors contain one fungal cell for every 1,000 to 10,000 cancer cells.

If you consider that a small tumor can be laden with a billion or so cancer cells, you can imagine that fungi may "have a big effect on cancer biology," he said.

Related: Dormant cancer cells may 'reawaken' due to change in this key protein

Straussman and his team found that each cancer type tended to be associated with its own unique collection of fungal species; these included typically harmless fungi known to live in humans and some that can cause diseases, like yeast infections.

In turn, these fungal species often coexisted with particular bacteria within the tumor. For now, it's unknown if and how these microbes interact in the tumor and if their interactions help fuel the cancers' spread.

The second Cell study uncovered similar results to the first but focused specifically on gastrointestinal, lung, and breast tumors, Nature reported. The researchers found that each of those three cancer types tended to host the fungal genuses Candida, Blastomyces, and Malassezia, respectively.

Both research groups found hints that the growth of certain fungi may be linked to worse cancer outcomes. For example, Straussman's group found that breast cancer patients with the fungus Malassezia globosa in their tumors showed worse survival rates than patients whose tumors lacked the fungus.

The second group, led by immunologist Iliyan Iliev at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, found that patients with a relatively high abundance of Candida in their gastrointestinal tumors showed increased gene activity linked to rampant inflammation, cancer spread, and poor survival rates, Nature reported.

Despite these early hints, neither study can definitively say if fungi actually drive these poor outcomes or if aggressive cancers just create an environment where these fungi can easily grow.

The studies also don't address if fungi can contribute to cancer development, pushing healthy cells to turn cancerous.

Both studies come with similar limitations. For example, both pulled tissue and blood samples from existing databases, and it's possible that some samples may have been contaminated with fungi during the collection process, Ami Bhatt, a microbiome specialist at Stanford University in California, told Nature.

Both research groups attempted to weed out such contaminants, but even with these precautions, Bhatt said that it would be best if the results could be replicated with samples taken in a sterile environment.

Straussman told STAT that these initial studies serve as a springboard for future research into mycobiota, meaning the communities of microbes associated with cancers.

"As a field, we need to evaluate everything we know about cancer," he said. "Look at everything through the lens of the microbiome – the bacteria, the fungi, the tumors, even viruses. There are all these creatures in the tumor, and they must have some effect."

Related content:

- Experimental rectal cancer drug caused all patients' tumors to disappear in small trial

- Drug tricks cancer cells by impersonating a virus

- Cancer patients weren't responding to therapy. Then they got a poop transplant

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.