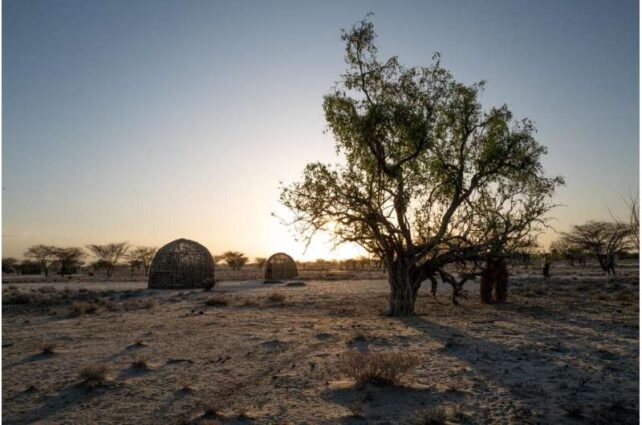

The Turkana people of Northwest Kenya have adapted to one of the driest places on Earth by relying predominantly on the milk, meat, and blood from their herds of camels and goats.

With up to 80 percent of their diet consisting of animal products, their meat-heavy diet would make the rest of us ill.

New research reveals the unique genes that allow this nomadic population to remain healthy, despite their limited access to wild edible vegetables.

"If you and I went on a Turkana diet, primarily eating lots of meat, fat, and protein, we'd probably get sick very fast," biologist Julien Ayroles told Robert Sanders at UC Berkeley News. "But this community has been eating these foods for many generations, and are adapted."

With permission from the community and its elders, Vanderbilt University genomicist Amanda Lea and colleagues conducted interviews and obtained urine and blood samples from 308 people in the Turkana community.

Some had continued their traditional nomadic lifestyles, while others had settled in towns or cities.

An astonishing majority of Turkana pastoralists were found to be chronically dehydrated but otherwise generally healthy. Comparing their genes with those of other indigenous communities in the region – almost 8 million gene variants in total – the researchers identified eight areas of consistent DNA differences.

One of those differences lies in the gene STC1, which causes the kidneys to retain more water. Lea and team suspect that this may help protect the kidneys from the extra waste products, such as purine, produced by a high intake of meat.

Too much purine can often lead to gout, which is not a common condition amongst the Turkana.

These genetic differences could be maladaptive for those who relocate to the city, with the potential to cause disease in a different environment, the researchers suspect. This supports the long-held theory that "evolutionary mismatch" may be behind many diseases prevalent in urbanized societies.

"[Evolutionary mismatch] occurs when previously advantageous variants, selected for in past ecologies, are placed in novel environments where they instead have detrimental effects," Lea and team explain in their paper.

The researchers hope this knowledge will help the Turkana and other indigenous peoples tackle the challenges of urbanization and other environmental changes they'll face in the future.

"Understanding these adaptations will guide health programs for the Turkana – especially as some shift from traditional pastoralism to city life," says Kenya Medical Research Institute biochemist Charles Miano. "It can help doctors anticipate health risks, like kidney strain or metabolic diseases, and design better prevention strategies."

This research was published in Science.