A new video provides a front-row seat to a cosmic drama that has been playing out for centuries.

Since 1604, when astronomers around the world recorded a new 'star' that appeared in the sky, humans have watched its evolution unfold.

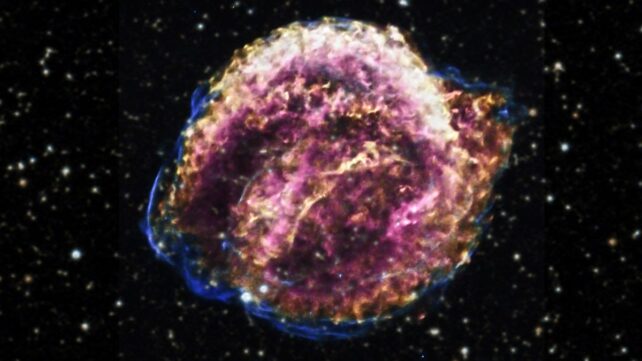

We now know that it wasn't a new star at all, but the explosive supernova death of a white dwarf, whose remains formed an expanding cloud of ejecta that continues to expand at breathtaking speeds to this day.

Thanks to NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, you can now take a peek for yourself.

Related: After 400 Years, Debris From This Supernova Is Still Not Slowing Down

In a new video, astronomers have compiled 25 years' worth of observations of the remnant of Kepler's Supernova, or SN 1604, revealing the astonishing changes visible even over such a short cosmic timespan.

Astronomers Jessye Gassel of George Mason University and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Brian Williams of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center presented the video at the 247th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Kepler's supernova remnant is extremely exciting for astronomers – a rare example of a supernova for which we have a clear kick-off timeline, dating back more than 400 years. It's also just 20,000 light-years away; not super-close, but close enough that, with today's instruments, its changes can be tracked in exquisite detail.

Those changes are fascinating, thanks in part to the kind of explosion that created the cloud – a Type Ia supernova. These occur when a white dwarf star in a binary system accretes so much mass from its companion that it is no longer stable, resulting in a cosmic kaboom.

Type Ia supernovae are important for a number of reasons. When they do explode, they have an absolute brightness peak, which is well known. This means that we can measure the distance to them with high accuracy and use them as distance gauges.

They're also a major source of heavy elements in the Universe; when a white dwarf explodes, the products of its core fusion spray out into space, where they can be absorbed into other objects as they form.

"Supernova explosions and the elements they hurl into space are the lifeblood of new stars and planets," Williams says. "Understanding exactly how they behave is crucial to knowing our cosmic history."

Kepler's supernova remnant is an important laboratory for understanding this process, so astronomers have watched it closely for decades. And it's moving fast enough that minute changes can be tracked even from 20,000 light-years away.

A previous 2020 study found that some of the knots in the expanding cloud of star guts have velocities up to 8,700 kilometers per second (around 5,400 miles per second).

The video contains snapshots of the supernova remnant recorded in 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025. Although a paper is yet to be published, the researchers plan to focus on measurements of motion in the ejecta, building on the results of a 2022 paper that mapped the speeds of the ejecta shock fronts in several places.

The visualization analysis shows other parts of the shock moving at speeds between 6,170 and 1,790 kilometers per second – about 2 and 0.5 percent of the speed of light, respectively.

Although that's faster than the Milky Way's escape velocity for a star, the front is expanding into gas and dust that will slow its momentum significantly. It will ultimately remain bound to the galaxy.

Eventually, over thousands of years, the debris from the supernova will dissipate. We're remarkably lucky to catch it in such a brief blink of cosmic time.

"The plot of Kepler's story is just now beginning to unfold," Gassel says. "It's remarkable that we can watch as these remains from this shattered star crash into material already thrown out into space."