Stimulating the brain with magnetic fields can help relieve the symptoms of depression in some people, but scientists haven't been sure precisely why it works. A new study offers some insight: The process reverses brain signals going in the wrong direction.

These neural streams of activity going in the wrong direction could also be used as a way of diagnosing depression in the future, according to the team behind the study.

Officially known as Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), the treatment is non-invasive, can be personalized to each patient, and has received regulatory approval. Finding out exactly how it works should enable further improvements in TMS.

"The leading hypothesis has been that TMS could change the flow of neural activity in the brain," says psychiatrist and behavioral scientist Anish Mitra from Stanford University in California. "But to be honest, I was pretty skeptical. I wanted to test it."

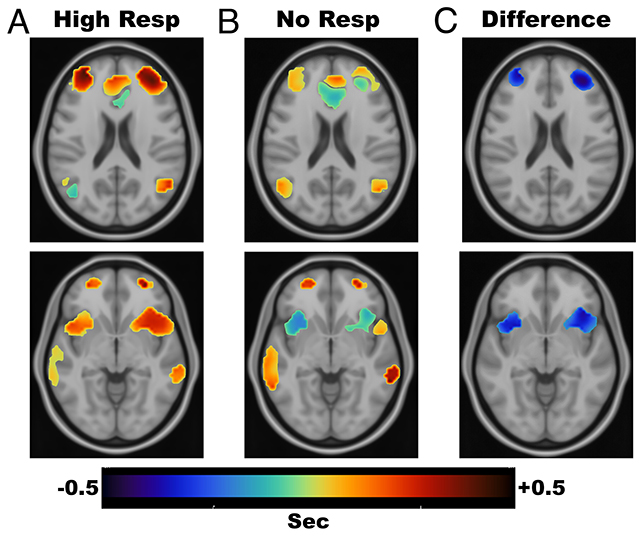

To do that, the researchers deployed a special mathematical approach to analyzing functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scans, which showed precise timings of activity in the brain – timings that also revealed the direction of neural signals.

The study involved patients diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. In one part, 10 were given Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy (SNT), a type of TMS, and another 10 were given a placebo-style treatment mimicking SNT without any actual magnetic stimulation.

Brain scans of all the participants with depression were also compared to scans of 102 healthy controls without a depression diagnosis, enabling the researchers to see the differences. Sixteen of those healthy controls were scanned using a different scanner from the other 85 and with different scan parameters.

One area stood out: the anterior insula, a part of the brain known to take biological signals from the body (like heart rate) and send signals to a part of the brain involved in processing emotions, the cingulate cortex.

In three-quarters of those with depression, the signals went the other way, from the emotional processing region back to the anterior insula. What's more, the higher the level of depression, the more signals were sent the wrong way.

"What we saw is that who's the sender and who's the receiver in the relationship seems to really matter in terms of whether someone is depressed," says Mitra.

"It's almost as if you'd already decided how you were going to feel, and then everything you were sensing was filtered through that. The mood has become primary."

That fits with what we know about depression. Typically pleasurable activities – reported by the anterior insula – are overridden by dominating signals from the part of the brain that sets our mood rather than it working in the other direction.

In the majority of patients with depression, a week of treatment with SNT was enough to get the brain signals traveling in the correct direction again. It confirms previous results showing the potential of this particular treatment.

While this haywire brain activity won't be present in everyone with depression, the researchers say it could help identify people for whom SNT would be helpful. Further analysis might reveal more about how brain signaling changes in people with depression.

We don't know just how permanent this brain signal fix might be, and the team wants to test it out on a larger group of people. However, it's an important insight into how depression affects the brain's wiring, made possible by analyzing scans in more detail than ever before.

"Behavioral conditions like depression have been difficult to capture with imaging because, unlike an obvious brain lesion, they deal with the subtlety of relationships between various parts of the brain," says neurologist Marcus Raichle from Washington University in St. Louis in Missouri.

"It's incredibly promising that the technology now is approaching the complexity of the problems we're trying to understand."

The research has been published in PNAS.