Scientists have identified a chain reaction that explains why our own bodies can turn against healthy cells, potentially transforming the way we look at autoimmune diseases and the way we treat them.

The reaction, discovered in 2017 after four years of research in mice, has been described as a "runaway train" where one error leads the body to develop a very efficient way of attacking itself.

The study focussed on B cells gone rogue. Ordinarily these cells produce antibodies and program the immune cells to attack unwanted antigens (or foreign substances), but scientists found an 'override switch' in mouse B cells that distorted this behaviour and caused autoimmune attacks.

"Once your body's tolerance for its own tissues is lost, the chain reaction is like a runaway train," said one of the team, Michael Carroll from Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School (HMS).

"The immune response against your own body's proteins, or antigens, looks exactly like it's responding to a foreign pathogen."

These B-cells-gone-awry could in turn explain the biological phenomenon known as epitope spreading, where our bodies start to hunt down different antigens that shouldn't be on the immune system's 'kill list'.

Epitope spreading has long been observed in the lab but scientists have been in the dark about how it happens, and why autoimmune diseases evolve over time to target an ever-expanding catalogue of healthy organs and tissues.

In this case the research looked at a mouse model of the lupus autoimmune disease, considered an archetypal or 'classic' type of autoimmune disease that many others are based on.

"Lupus is known as 'the great imitator' because the disease can have so many different clinical presentations resembling other common conditions," said one of the researchers, Søren Degn from Boston Children's Hospital and Aarhus University in Denmark, at the time.

"It's a multi-organ disease with a plethora of potential antigenic targets, tissues affected and 'immune players' involved."

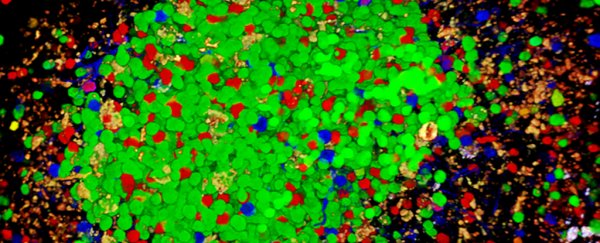

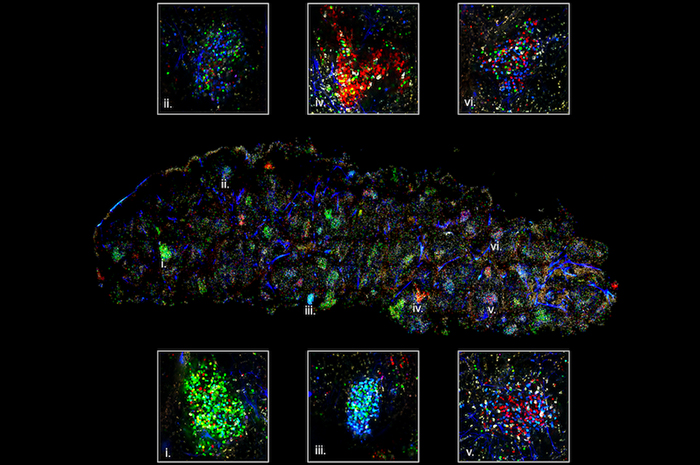

The confetti technique shows different antibodies in different colours. Credit: Carroll Lab

The confetti technique shows different antibodies in different colours. Credit: Carroll Lab

The team used what's known as a 'confetti' technique in their imaging, where fluorescent marker proteins were used to track different B cells in the body.

When B cells sense a foreign body – or something healthy that appears to be a foreign body – they swing into action in clusters called germinal centres. Those centres are why your lymph nodes become swollen when you've got a cold coming on, for example.

B cell clones actually battle each other out inside these centres so the body can determine which antibody is best suited to fight the threat, and in the case of this study that meant one colour of protein winning out against the others.

The problem comes when the body incorrectly identifies a normal protein as a threat. When that happens, the B cell selection process produces what are known as autoantibodies that prove very effective at harming our own bodies.

"Over time, the B cells that initially produce the 'winning' autoantibodies begin to recruit other B cells to produce additional damaging autoantibodies – just as ripples spread out when a single pebble is dropped into water," said Degn.

This has only been examined in mice so far, but the researchers now want to use the confetti model to look at how B cell production of autoantibodies is regulated and gets sped up.

Eventually, blocking the germinal centres in some way could put a break in the vicious cycle that autoimmune diseases create. It would effectively block the immune system's short term memory, but that kind of treatment is still a long way off.

For now, it's a promising step towards a better understanding of this runaway biological train that's so hard to stop.

"This finding was such a surprise," said Carroll. "It not only tells us that autoreactive B cells are competing inside germinal centres to design an autoantibody, but then we also see that the immune response broadens to attack other tissues in the body, leading to epitope spreading at the speed of wildfire."

The research was published in Cell.

A version of this story was just published in September 2017.