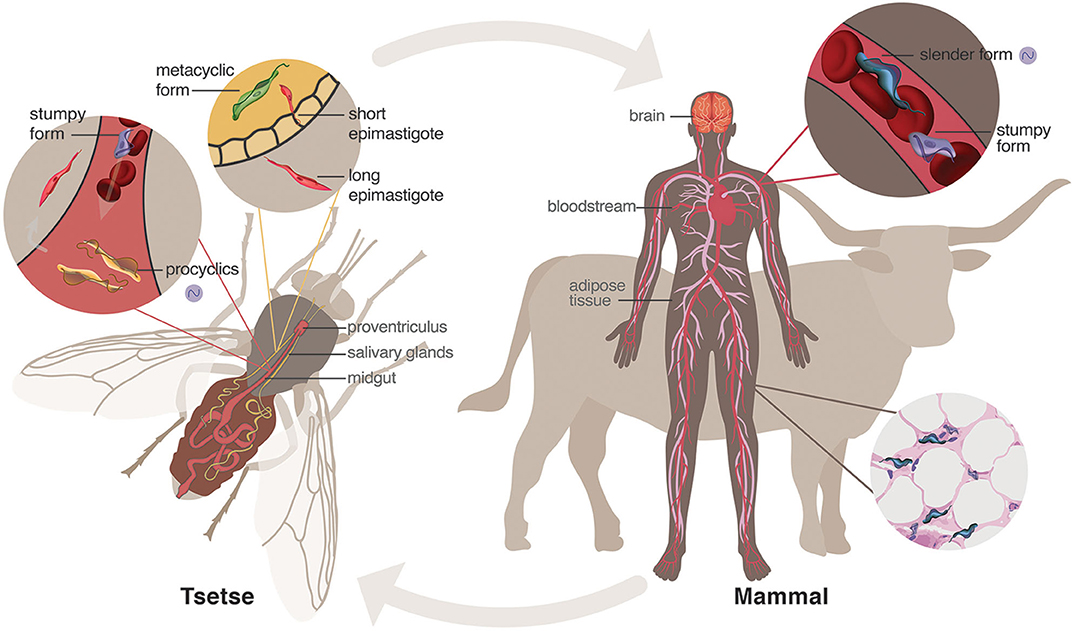

It starts with an innocent bite from a tsetse fly – an all too common occurrence in sub-Saharan Africa.

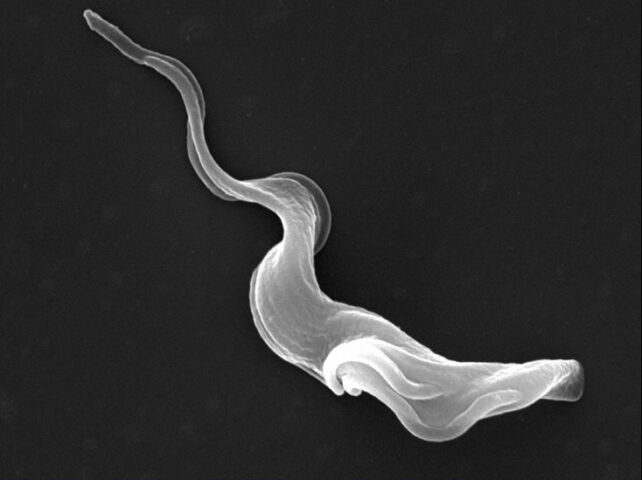

Before a person knows it, tiny microscopic parasites known as Trypanosoma are swimming in their bloodstream, playing "hide and seek" with their immune system.

For months, or even years, these ribbon-like unicellular free-riders produce few to no symptoms, quietly preparing themselves to conquer the body's 'boss'.

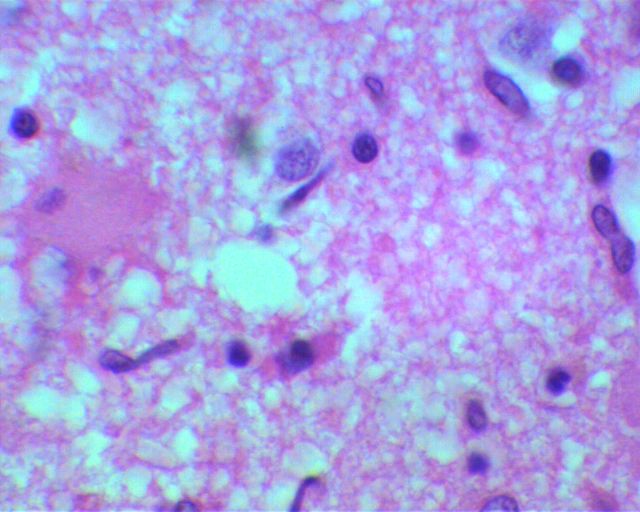

When the parasites finally invade the brain, they nestle in neural tissue and trigger a whole host of cognitive issues, including personality changes, paranoia, confusion, hallucinations, poor coordination, sensory disturbances, and convulsions.

People with later stages of the infection behave in extremely erratic ways, to the point where sudden episodes of fury can even place family members at risk of violence.

According to The New York Times, even the gentle touch of water can suddenly feel agonizing to those infected, causing them to scream with pain.

It's an absolutely horrifying, uncontrollable state, made even more terrifying by a lack of available treatments. Left untreated, this neglected tropical disease can lead to a coma and nearly always death.

Circadian disruptions seem to play a big role in symptoms, especially insomnia at night and excessive bouts of sleep during the day.

That's why the infection is called 'sleeping sickness', or, more officially, Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT).

Now, there's new hope in the quest for its eradication.

Scientists have known about HAT for over a century now, and yet it's still not clear how the parasite actually invades the human brain.

HAT is caused by two subspecies of Trypanosoma endemic to Africa, but most cases today are triggered by T. brucei gambiense in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This subspecies is often said to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, which is a defensive wall that keeps most toxins and pathogens out of the central nervous system.

Nevertheless, some studies on rodents suggest that T. b. gambiense might actually cross the blood-cerebrospinal border (BCB), which separates the fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord from blood-infused tissue.

Regardless of the way it gets to the brain, once the parasite arrives there, it's very hard for medicine to target it without causing unwanted damage.

In the past, physicians have relied on toxic treatments like arsenic to rid people of the parasite, causing roughly 5 percent of patients to die in the process.

For years now, treatments for sleeping sickness have been confined to multiple painful injections, sometimes in the spine. Even then, success is not guaranteed. Between 30 and 50 percent of patients who receive these forms of therapy relapse.

A new oral drug, tested in clinical trials at the end of last year, could be a saving grace for hundreds of people in Africa who continue to get diagnosed with this harrowing illness each year.

The medicine only needs to be taken once, and it is 95 percent effective at curing the disease.

Even better, there's a chance it could stop future epidemics from breaking out, like those that claimed the lives of thousands in the 1920s and in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.

Today, the World Health Organization (WHO) has committed to eradicating HAT by 2030. Infectious disease specialist Jacques Pépin told NPR in 2022 that was going to be "tough".

"When you're trying to eradicate a disease, it's always the last few miles that are difficult. It's very hard to reach the magical number of zero cases," Pépin explained.

But that doesn't mean it's not worth trying. Previously, WHO wanted to eradicate HAT by 2020. Back then, however, the only oral medicine available for the illness involved a 10-day course of treatment.

Compared to other diseases, HAT impacts only a small number of people, which means that drug companies haven't been incentivized to search for a better cure.

Public health officials at WHO have been working tirelessly since 2013 to change that.

Thanks to this new and impressive-looking oral medicine, experts now say sleeping sickness is truly on its way to elimination.