Human activity is heating up the planet, putting wildlife in danger, and even altering Earth's spin. Now it appears we're also having a seriously detrimental effect on the planet's natural salt cycle, a new study reveals.

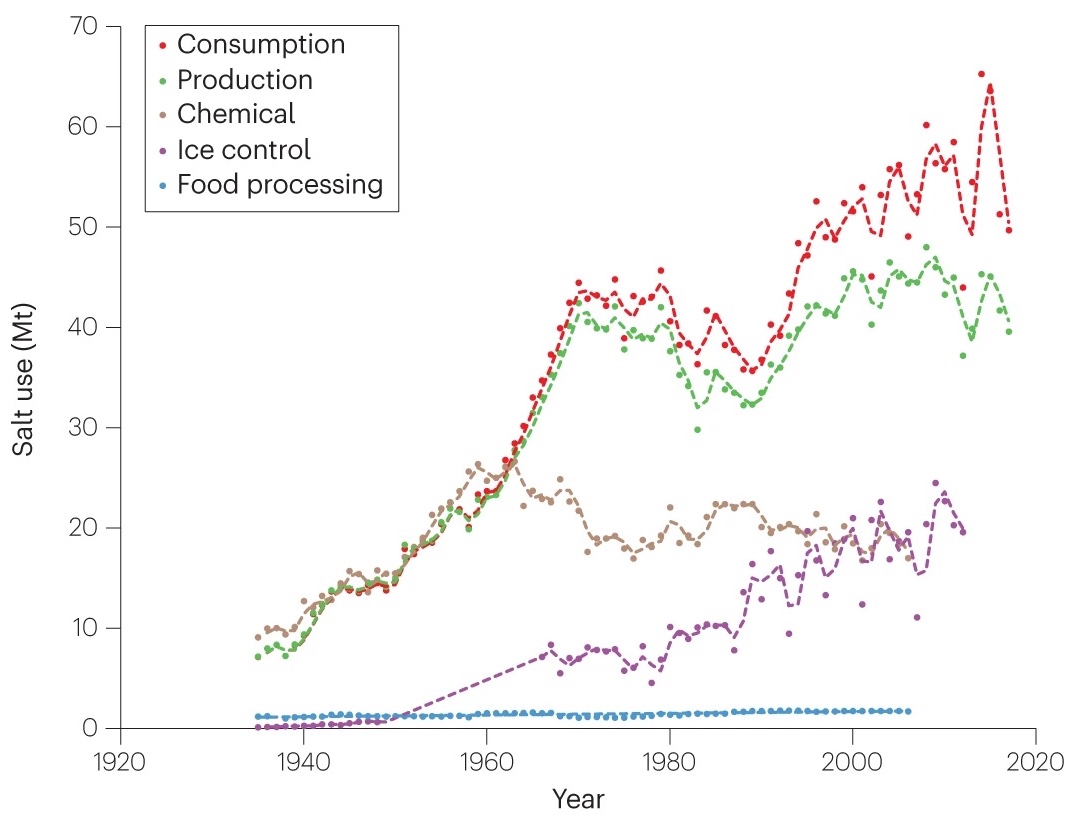

While geological and hydrological processes naturally bring salt up to Earth's surface over long time spans, we're speeding up this natural flow due to mining, land development, and the use of road salts to melt ice.

Researchers from the University of Maryland, the University of Connecticut, Virginia Tech and other institutions have all combined their expertise to document what they describe as an "existential threat" to supplies of freshwater.

The team looked at a variety of different salts – not just the sodium chloride variety most of us readily use in our cooking – and in a range of different environments, including salt concentrations in rivers and in soils. Certain events, like lakes drying up, are even adding to salt concentrations in the air.

"Twenty years ago, all we had were case studies," says ecologist Gene Likens, from the University of Connecticut. "We could say surface waters were salty here in New York or in Baltimore's drinking water supply."

"We now show that it's a cycle – from the deep Earth to the atmosphere – that's been significantly perturbed by human activities."

Among the study's findings are that around 2.5 billion acres of soil worldwide have been affected by human-caused salinization, and that salt used to deice roads is also finding its way into the air.

The increasing saltiness of sources of freshwater is one of the biggest concerns. If the trend continues, finding enough water for the world's population to drink could become a real challenge – and that's before we get to the damage to other animals and their habitats.

"If you think of the planet as a living organism, when you accumulate so much salt it could affect the functioning of vital organs or ecosystems," says geologist Sujay Kaushal from the University of Maryland.

Salt levels affect more aspects of life than you might realize, from how much snow forms on mountaintops to how likely we are to pick up respiratory illnesses.

The researchers are calling for more to be done to assess our impact on the salt cycle, and to reduce that impact: one starting point could be the 44 billion pounds of salt distributed on US roads each year. Ultimately, further study and regulation is going to be required.

"This is a very complex issue because salt is not considered a primary drinking water contaminant in the US, so to regulate it would be a big undertaking," says Kaushal.

"But do I think it's a substance that is increasing in the environment to harmful levels? Yes."

The research has been published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.