At the bottom of that glass of Scotch you drank last night, a unique landscape is forming.

Now researchers have teamed up with a photographer and worked out why - and the results will help scientists to better understand fluid dynamics.

US photographer Ernie Button first became intrigued with the patterns that whisky left at the bottom of a glass when he married into his wife's scotch-loving family and noticed while doing the dishes that different blends were forming different patterns at the bottom of the glasses.

"It's a little like snowflakes, in that every time the Scotch dries, the glass yields different patterns and results," Button told Helen Thompson from The Smithsonian.

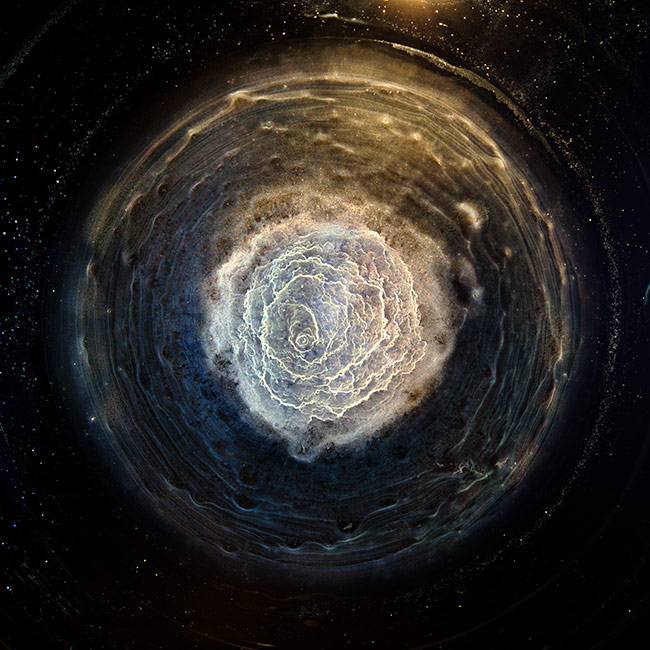

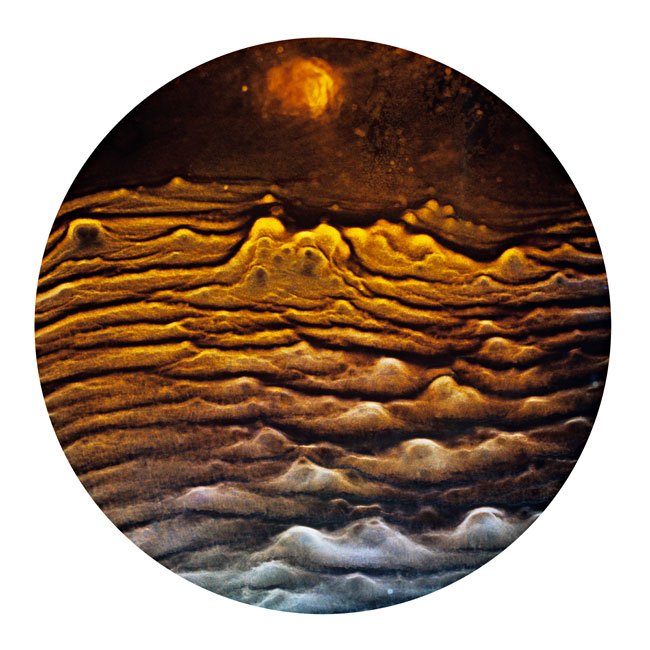

Fascinated, he started to photograph them. After playing around with flashlights and desk lamps, he created a series of stunning images (like the one above) that looked more like alien landscapes or smudges of bactera rather than the dregs of last night's fun.

But he was still curious about what was causing the differing patterns - the age of the scotch didn't seem to make a difference, but the brand did.

Intrigued, he reached out to Howard Stone, an engineer who was then at Harvard University but is now at Princeton, who set his lab to work experimenting with video microscopy so that they could study the drying process in detail.

The results of this research were presented last week at a meeting of the American Physical Society in San Francisco.

What Stone's lab suspected was that something called the Marangoni effect might be at play, as Thompson reports for The Smithsonian.

The Marangoni effect was first described in the 19th century, and is governed by the fact that alcohol and water have different surface tensions, which means they're attracted to other surfaces in different amounts. "Alcohol has a lower surface tension than water, and alcohol evaporation drives the surface tension up and pushes more liquid away from areas of high alcohol concentration," writes Thompson.

But with whisky, the patterns the team saw were more consistent, with particles settling in the middle of a droplet of liquid, so it seemed something else was going on.

To work it out, the team compared the drying of real whisky to a mixture of alcohol and water that mimicked the composition of whisky (around 40 percent ethanol, 60 percent water). They found that while the fake whisky followed the Marangoni effect and produced clean rings as it dried, the real whisky didn't.

They then experimented with their fake whisky by adding a soap-like compound, which still didn't produce the same patterns as real whisky. Finally, they tried adding a polymer to the mix, and at last the fake whisky started to act like the real drink.

This means, Stone's team believes, that it's the small amounts of additives that each whisky distillery adds in differing amounts that controls the patterns at the bottom of the glass - not alcohol content or age.

Why does it matter? The research provides new insight into fluid dynamics, which is crucial in any field that relies on liquids, such as medicine and engineering. In particular, this type of work could be used to help produce more sophisticated printing inks and other liquids that contain additives.

And for lovers of a fine whisky, the research is just another fascinating fact about the drink to bring up at dinner parties, and proof that you really can find answers at the bottom of a glass.

See a couple of Ernie's amazing photographs below, and check out the full series, titled Vanishing Spirits: The Dried Remains of Single Malt Scotch, over on his site. Cheers.

The Macallan 150, Credit: Ernie Button

Aberlour 108, Credit: Ernie Button

Source: The Smithsonian, Ernie Button