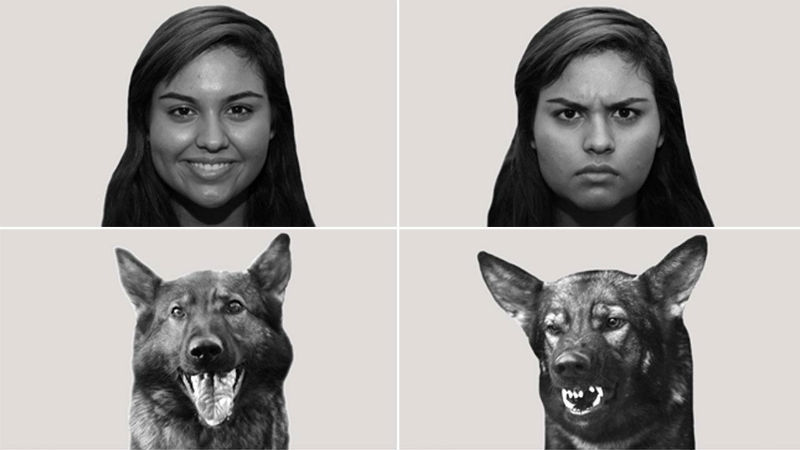

Can your dog really tell the difference between when you're happy, sad, or somewhere in the middle? The answer is yes, according to a new study that looked at the response of 17 dogs to images and sounds designed to evoke a particular emotional state.

The image and sound pairings covered both humans and dogs and varied from positive (happy and playful) to negative (angry or aggressive). In each case, a dog or human facial expression was displayed at the same time as an audio clip of a bark or a voice. During the testing, the researchers found that the dogs' attention was held for longer when the visuals matched the audio, whether human or canine.

That may not sound like the most compelling piece of evidence, but the team from the University of Lincoln in the UK and the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil says it shows that the dogs are combining information from different senses to judge emotion - something that has only been previously observed in human beings.

It's evidence that the animals are forming "abstract mental representations of positive and negative emotional states" and not just showing learned behaviours, the researchers say.

"Previous studies have indicated that dogs can differentiate between human emotions from cues such as facial expressions, but this is not the same as emotional recognition," said Kun Guo from the University of Lincoln. "Our study shows that dogs have the ability to integrate two different sources of sensory information into a coherent perception of emotion in both humans and dogs. To do so requires a system of internal categorisation of emotional states."

Natalia Albuquerque

Natalia Albuquerque

According to report co-author Daniel Mills, also from Lincoln, there is a difference between associative behaviour (a dog becoming sheepish in response to an angry voice, for example) and the behaviour being exhibited in this test: namely, recognising a range of different cues to assess emotional arousal in another person or dog.

"Importantly, the dogs in our trials received no prior training or period of familiarisation with the subjects in the images or audio," says Mills. "This suggests that dogs' ability to combine emotional cues may be intrinsic. As a highly social species, such a tool would have been advantageous and the detection of emotion in humans may even have been selected for over generations of domestication by us."

The results have been published in the journal Biology Letters.