"How often do you poop?" might sound like a very personal question, but your answer could reveal quite a lot about your overall health.

A study published in July 2024 investigated how often 1,425 people went number two, and compared those stats to their demographic, genetic, and health data.

The healthiest participants reported pooping once or twice a day – a 'Goldilocks zone' of bowel movement frequency.

Pooping too often or too rarely were both associated with different underlying health issues, the team led by researchers at the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB) found.

Related: Something in Your Poop May Predict an Imminent Death

"This study shows how bowel movement frequency can influence all body systems, and how aberrant bowel movement frequency may be an important risk factor in the development of chronic diseases," says ISB microbiologist Sean Gibbons, the corresponding author of the report.

"These insights could inform strategies for managing bowel movement frequency, even in healthy populations, to optimize health and wellness."

Watch the video below for a summary:

The study investigated the bathroom habits of people who were "generally healthy" – that is, with no history of kidney or gut issues like kidney disease, irritable bowel syndrome, or Crohn's disease.

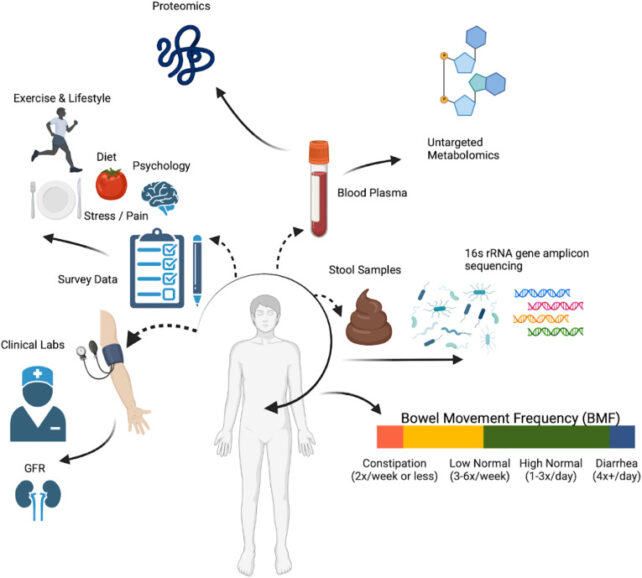

Participants self-reported how often they dropped the kids off at the pool, and the researchers organized them into four categories: constipation for those reporting one or two bowel movements per week; low-normal for three to six movements per week; high-normal for one to three movements per day; and diarrhea for four or more watery stools per day.

The researchers also analyzed patients' blood metabolites and chemistry, their genetics, and the gut microbes present in their stool samples.

The team looked for possible associations between bowel movement frequency and these health markers, as well as other factors like their age and sex.

In general, those who reported less frequent bowel movements tended to be women, younger, and with a lower body mass index (BMI). But even accounting for these factors, people with constipation or diarrhea showed clear links to underlying health issues.

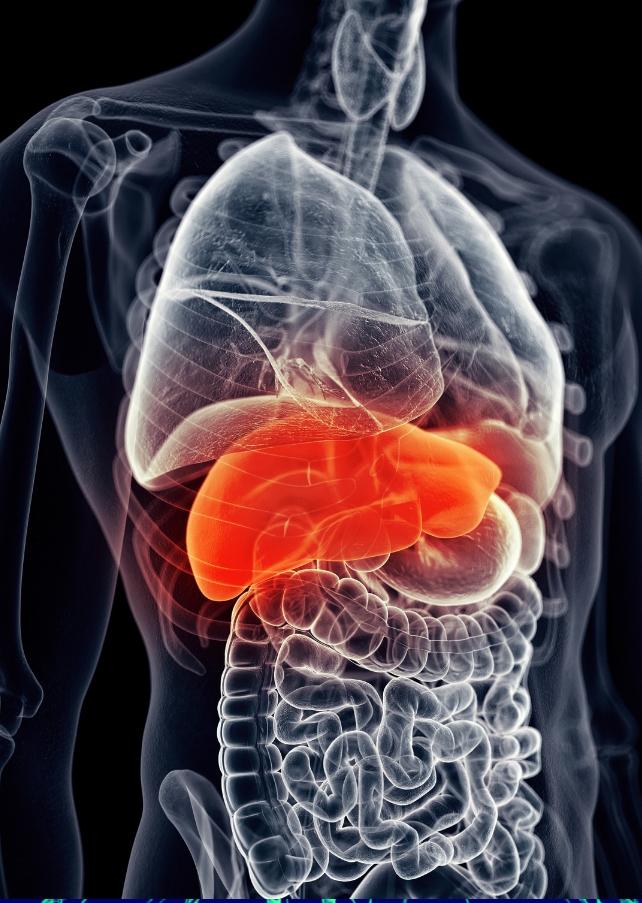

Bacteria usually found in the upper gastrointestinal tract were more common in stool samples from participants with diarrhea. Their blood samples, meanwhile, showed biomarkers associated with liver damage.

Stool samples from people with less frequent bowel movements had higher levels of bacteria associated with protein fermentation. This is a known hazard from constipation.

"If stool sticks around too long in the gut, microbes use up all of the available dietary fiber, which they ferment into beneficial short-chain fatty acids," says Johannes Johnson-Martinez, a bioengineer at ISB.

"After that, the ecosystem switches to fermentation of proteins, which produces several toxins that can make their way into the bloodstream."

Sure enough, some of these byproducts were found in these patients' blood samples. Particularly enriched was a metabolite called indoxyl-sulfate, a known product of protein fermentation that can damage the kidneys.

The team suggests the finding is potential evidence of a causal link between bowel movement frequency and overall health.

There is some hope that people can change their habits and, as a result, their health. Recent research suggests your gut microbiome can shift a lot faster than you might think.

For instance, a 2025 study from Germany, yet to undergo peer review, tracked inactive adults who began resistance training twice or three times a week. Those who gained the most strength showed changes in the makeup of their gut bacteria in just eight weeks.

These kinds of changes might help some people move out of the constipation or diarrhea categories and into a healthier bowel-movement range.

Those in the Goldilocks zone of pooping reported eating more fiber, drinking more water, and exercising more often. Their stool samples also showed high levels of bacteria associated with fermenting fiber.

A clinical trial published in 2025 by US researchers found that people with a lot of methane-producing microbes in their guts are especially efficient at turning dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids.

This suggests that both the amount of fiber and the specific mix of microbes in an individual's gut are important, which explains why two people eating the same diet can experience different health outcomes.

Related: Here's How to Avoid Food Poisoning This Thanksgiving

Of course, everybody's found themselves at one extreme or the other at some point in their lives, after catching a stomach bug or eating too much cheese. But this study was looking at people's everyday routine, and reveals how our own version of 'normal' could hint at health issues we weren't aware of.

The research was published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

An earlier version of this article was published in July 2025.