If you ever lie awake at night wondering just how likely you are to die from an asteroid impact within your lifetime, a new paper has you covered.

A team led by physicist Carrie Nugent of the Olin College of Engineering in the US has calculated not just how likely it is that an asteroid will hit Earth during an average human lifespan, but how likely that impact is to cause human deaths when compared to a selection of other rare, preventable ways to die.

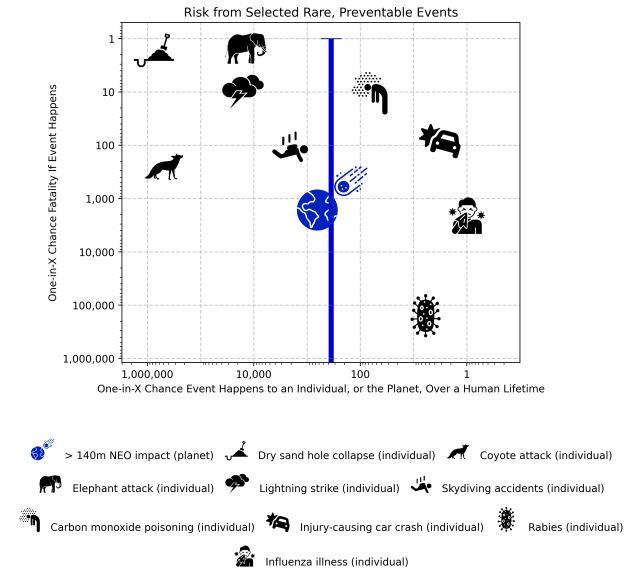

The bad news is that death by asteroid impact is more likely to happen to you than death by rabies. The worse news is that death from a car accident is more likely than death by asteroid impact.

The great news is that all of these likelihoods are pretty low, and you can probably live your life without too much worry (although you might want to wear a seat belt).

Related: Forget Your Troubles by Looking at These Weird But Totally Real Science Illustrations

There are good reasons to compare the risk of death by asteroid impact with the risk of death by other preventable mechanisms. Although it's difficult to calculate exactly what the risk is – there could be a lot more potentially hazardous asteroids out there than we've found to date – an asteroid impact could very well be preventable too.

NASA demonstrated this back in 2022, when the space agency deliberately crashed a spacecraft into an asteroid to try to knock it off course. The mission was more successful than expected, with the asteroid in question showing a much greater change in its orbit than anticipated.

Such missions are quite costly, and require a lot of planning. By placing the risk of an asteroid impact in context with other risks, scientists can compare the potential expenditure involved with the expenditure of, say, a rabies vaccine program, or car safety features.

So, Nugent and her colleagues collected available data on the population of near-Earth objects, as well as models of these populations and previous risk assessments for asteroids more than 140 meters (460 feet) in size. From this, they calculated the impact frequency for this kind of object.

The next step was to collect available data on different kinds of deaths and compare the probability of each event occurring during the average global human lifetime of 71 years.

"Chapman and Morrison (1994) previously placed an asteroid impact in context with other causes of death such as murder, fireworks accidents, and botulism. In that work, they considered the chance of death due to an impact alongside the chance of death due to other factors," the researchers write.

"This work addresses a slightly different question; we place the chance of an impact occurring anywhere on Earth relative to the chance of other events of concern happening to an individual. This work is therefore intended to provide context to those who wish to know the probability that a greater-than-140-meter impact will occur, anywhere on Earth, in their lifetime."

They collected data on nine other potentially fatal events: dry sand hole collapse (that's when a person digging a hole, on a beach for example, has the sand collapse on them); elephant attack; lightning strike; skydiving accidents; carbon monoxide poisoning; injury-causing car crash; rabies; and influenza illness.

They then calculated how likely a person would be to experience one of these events; and then how likely the person would be to die of the same (many people, for example, catch the flu without dying). This is obviously regionally variable; someone in Australia is far less likely than someone in the US to die of coyote attack or rabies.

You can see the results for yourself in the graph. Flu is similarly deadly to an asteroid impact, but far more likely to occur; the law of averages therefore suggests that it's going to kill more people than an asteroid does. Dry sand hole collapse is almost always fatal, but has almost a one in 1 million chance of occurring within a human lifetime.

Of course, translating risk assessments like these to the real world requires some context. After all, more than three people die per year of dry sand hole collapse, tragically with an average age of 12. As far as we know, no humans have ever died from an asteroid impact. As the dinosaurs might tell you, the toll from a single strike could more than make up for a history of misses.

So the question is, is Earth overdue for another asteroid? Is caution and prevention warranted, or are we worrying unnecessarily? Does the above information comfort you, or make things worse?

It's a bit hard to tell, really. But at least we know to stay away from sand holes.

The research will soon appear in the Planetary Science Journal. In the meantime, it's available on preprint server arXiv.