You've probably heard that every human on Earth has a unique set of bacterial colonies living in their gut, and this 'microbiome' has been linked to everything from stoke and chronic fatigue risk, to your ability to control your appetite and weight.

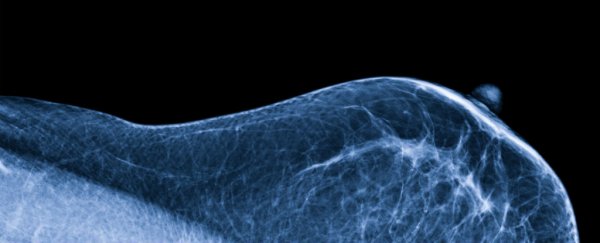

What you might not be aware of is the fact that bacteria also live in women's breast tissue, and new research has found evidence that a person's unique breast microbiome can either prevent or promote the growth of breast cancer.

It's thought that just 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancers are hereditary, meaning there are many different factors that can contribute to a person's risk, including age, weight, race, and previous cancer treatments.

Interestingly, since the 1960s, studies have found that pregnancy and breastfeeding are both associated with a lower risk of breast cancer, with women who haven't had a full-term pregnancy after the age of 30 exhibiting a higher risk than those who have.

More recently, scientists have attempted to find a biological cause to explain this link, and have suggested that the bacteria present in breast milk could play a role in protecting the mother from developing breast cancer. At that time, there was no evidence of bacteria in the actual breast tissue.

In fact, until just two years ago, scientists had assumed that breast tissue was entirely sterile - meaning it contains no bacteria whatsoever.

A 2014 paper changed all of that, when scientists from Western University in Ontario, Canada revealed that breasts actually contain a diverse community of bacteria, which could contribute to maintenance of healthy breast tissue by stimulating nearby immune cells.

To investigate this further, the team conducted a new study to find out exactly what kinds of bacteria are present in the breast tissue, and to figure out if populations look different in women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer, and those who haven't.

They analysed bacterial DNA from breast tissue samples from 58 women who were being treated with lumpectomies or mastectomies for benign (13 participants) or malignent cancerous tumours (45 participants), and compared those to samples from 23 healthy women who had never been diagnosed with breast cancer.

They found that in the women with breast cancer, there were significantly higher levels of Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, and Bacillus bacteria, which in previous studies have been shown to induce double-stranded breaks in DNA in human HeLa cells - a particular type of DNA damage that's been linked to the development of cancer.

"Double-strand breaks are the most detrimental type of DNA damage," the researchers explain.

The participants without breast cancer, on the other hand, had higher incidences of Lactococcus and Streptococcus bacteria, which are thought to have strong anticarcinogenic properties.

According to the team, one example of this is the bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus, which produces antioxidants that have been shown to neutralise a class of molecules called reactive oxygen species, which cause the kind of DNA damage that has been linked to cancer.

In fact, those double-stranded breaks we mentioned earlier are actually thought to be caused by reactive oxygen species, so it could be that some women have bacteria in their breasts that actively encourage the development of breast cancer, while others have bacteria that can help prevent it.

The results "suggest that microbes in the breast, even in low amounts, may be playing a role in breast cancer - increasing the risk in some cases and decreasing the risk in other cases," one of the researchers, Gregor Reid, told Knvul Sheikh at Scientific American.

To be clear, this is a very small sample size, and is in no way representative of the diversity of women all over the globe who could be affected by what is now the most common cancer in women worldwide.

But the good news is that if further research does confirm the team's hypothesis that certain bacterial colonies increase or decrease a woman's chance of developing breast cancer, you're not stuck with the microbiome you're born with.

The team suggests that if we can confirm that certain species of bacteria can improve a woman's chance of avoiding breast cancer, they could be administered as a probiotic to ensure women have more protective bacterial colonies in the future.

"Colleagues in Spain have shown that probiotic lactobacilli ingested by women can reach the mammary gland. Combined with our work, this raises the question, should women - especially those at risk for breast cancer - take probiotic lactobacilli to increase the proportion of beneficial bacteria in the breast?" Reid says in a press release.

"To date, researchers have not even considered such questions, and indeed some have balked at there being any link between bacteria and breast cancer or health."

We're interested to see how this research progresses, but at least we now know that there's nothing 'sterile' about the female breast - they're just as alive as our stomachs.

The results have been published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.