One of the world's most common viral infections could underlie virtually every case of lupus, according to a recent study providing the strongest evidence yet for a link.

The research, led by scientists at Stanford University, has found that the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) could be the trigger behind the 'cruel mystery' of this chronic autoimmune disease.

EBV is the pathogen that causes 'kissing disease' (or mononucleosis), and according to the new findings, it can directly infect and reprogram specific immune cells, potentially driving the onset of systemic lupus erythematosus – better known as simply lupus.

"This is the single most impactful finding to emerge from my lab in my entire career," claims immunologist and head of the lab William Robinson.

"We think it applies to 100 percent of lupus cases."

Related: Serotonin Could Play an Unexpected Role in Cancer, Scientists Discover

The vast majority of adults in the world have been exposed to EBV at some point in their lives, with the virus causing little to no fuss as it lies latent in their body's cells.

Those with lupus, however, show a deeper infection, possibly because they acquired a more virulent EBV strain. Among patients with the autoimmune condition, researchers found the percentage of B cells infected with EBV is about 1 in 400. That's 25 times higher than in healthy individuals.

In the lab, the infection flicked a switch in B cells, activating a system that 'turns on' their pro-inflammatory genes.

This has the potential, "to promote systemic disease–driving autoimmune responses," the authors argue, led by immunologist Shady Younis from Stanford.

The discovery could help solve the long-standing mystery of what triggers lupus in the first place and why its symptoms go through seemingly random cycles of flaring and settling.

Lupus causes the immune system to mistakenly attack the body's own healthy tissues, causing widespread inflammation with potentially severe, life-threatening outcomes.

The disease was first mentioned in historical records way back in 850 CE, and yet to this day, there is no known cause or cure. Only in the 19th century did experts officially recognize and describe lupus, which can cause a rash resembling a wolf's bite (hence the historical Latin name).

The enduring mystery of lupus is often pinned down to its complex nature, possibly triggered by numerous interacting factors, such as nutrient deficiencies, genetics, hormonal issues, or infections.

The new research from Stanford suggests there really may be a unifying explanation – one with viral origins.

Related: Lupus Tracked to Changes in a Single Gene That Tames The Immune System

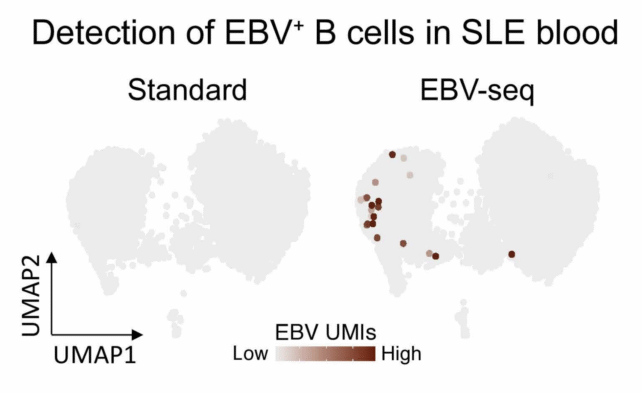

For years now, researchers have suspected that EBV is linked to lupus. The virus is known to infect B cells, and B-cell activity is known to be imbalanced in those with lupus. The trouble is, EBV is hard to measure when it infects and hides out in B cells.

Researchers at Stanford devised a clever way to find which of these white blood cells are infected with the virus.

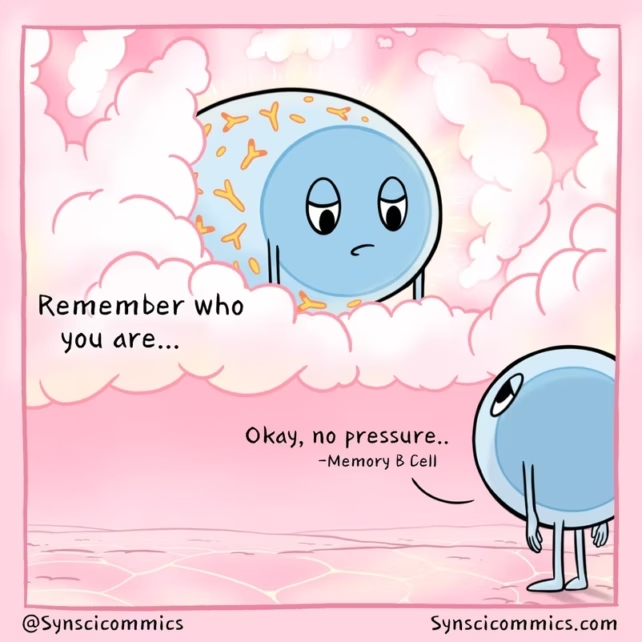

Using their new sequencing technique, the team demonstrated that people with lupus have significantly more EBV-infected B cells than those without lupus, especially memory B cells, which enable rapid immune responses.

Of all the hundreds of billions of B cells in a healthy human body, only about 20 percent are 'autoreactive', or primed to produce antibodies and activate killer immune cells.' But when EBV infects latent B cells, it appears to flip them back into a pro-inflammatory state.

"Our findings provide a mechanistic basis for why only a small fraction of EBV-infected individuals develop SLE," the authors conclude.

The mechanism is supported by a recent immunotherapy for lupus, which hunts down and replaces faulty B cells. It showed remarkable benefits in clinical trials, achieving remission-like outcomes.

Virologist Guy Gorochov from Sorbonne University in France, who was not involved in the current study, told The Guardian's Hannah Devlin that the work was "impressive.

"It's not the final paper about lupus," he added, "but they've done a lot and developed an interesting concept."

Going forward, the findings may even be relevant to other autoimmune conditions linked to EBV, such as multiple sclerosis, long COVID, and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.

"Practically the only way to not get EBV is to live in a bubble," Robinson says.

The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.