As anyone living with chronic fatigue syndrome knows, it can be an infuriating condition made worse by the lack of understanding and no treatment options.

But people might be buoyed by the efforts of researchers like Maureen Hanson, a molecular biologist at Cornell University who has revisited the viral origins of chronic fatigue syndrome (also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME/CFS) in a new paper.

Historical evidence suggests large numbers of ME/CFS cases are likely to have been triggered by viral infections. The question is which virus is the likely culprit.

Digging through the literature, Hanson thinks there could be a few.

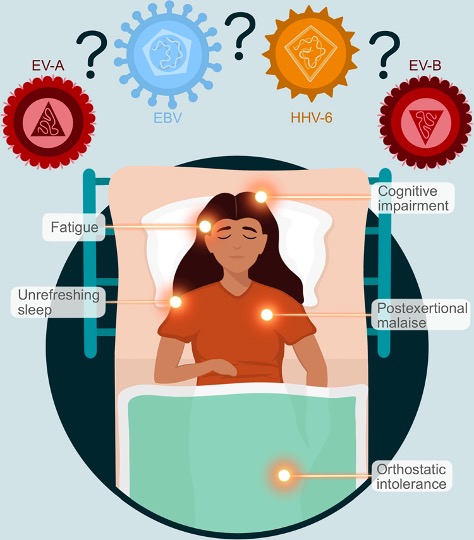

ME/CFS is an umbrella term for a constellation of disabling symptoms that include muscle pain (myalgia) and effects on the brain (encephalo), spinal cord (myel), and inflammation (itis) – hence the name, myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Unrelenting fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, and post-exertional malaise (a worsening of symptoms sometime after exertion) are other dimensions of the syndrome which is best described in people's own words.

While we might think of ME/CFS as a very isolating condition – which it is – cases sometimes cluster together. Dozens of documented outbreaks of ME/CFS have occurred in the past, beginning in the 1930s. The causes of these outbreaks went unidentified, although some coincided with viral infections.

Hanson estimates around 67 million people live with ME/CFS worldwide, as of 2020. But of course, that was before the COVID-19 pandemic and the tsunami of long COVID, which has parallels to ME/CFS.

Hanson says before SARS-CoV-2 emerged, the ability of RNA viruses to persist in tissues for long periods "was largely ignored". But now, with the growing recognition of post-viral illnesses, researchers have looked anew at the link between viral infections and conditions such as ME/CFS.

In her latest review paper, Hanson outlines why one particular group of viruses called enteroviruses might be the "most likely culprit" of ME/CFS.

Enteroviruses are a group of RNA viruses named for the way they enter the body to cause infections: through the intestine. Their role in ME/CFS has been long suspected, but largely disputed.

Studies have detected persistent enteroviral infections in people with ME/CFS. But over the years inconclusive results from studies comparing blood and tissue samples from people with ME/CFS to unaffected individuals deterred researchers from pursuing the link further.

"Ignoring the abundant evidence for enterovirus (EV) involvement in ME/CFS has slowed research into the possible dire but hidden consequences of EV infections, including persistence in virus reservoirs," Hanson writes.

Pinning down a viral culprit for ME/CFS is tricky because blood tests can only definitely point to a specific virus during the acute phase of infection. After that they will be awash with the antibodies a person's body has raised against all sorts of viruses from past infections.

What's more, by the time a person develops ME/CFS and receives a formal diagnosis (if they do), they or their treating doctor might not make the connection between their illness and a previous viral infection.

Up to half of enteroviral infections are asymptomatic, and people with ME/CFS who participate in research studies have likely been unwell for years. Enteroviruses are also very common, and often cause mild illness.

"Approximately one-third of ME/CFS patients cannot trace their onset to a flu-like illness," explains Hanson. "Quite possibly, they could have had an asymptomatic case or a mild one long before the onset of the characteristic ME/CFS symptoms."

Modern genetic sampling techniques might be better able to detect low amounts of residual virus hiding out in cells and tissues, and help figure out which viruses are possibly involved, Hanson suggests.

Other viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), are also thought to trigger ME/CFS, although the mechanisms are equally complex.

Like other human herpes viruses, EBV can hide out in the body, evading the immune system for years until stress or some other illness reactivates the virus.

While viral triggers of ME/CFS are once again attracting attention, we shouldn't discount other possible mechanisms that may be contributing to this debilitating condition.

Malfunctioning mitochondria, the energy factories of our cells, and low levels of two key thyroid hormones have recently been implicated in the condition – along with a host of genetic variants that a lot of people with ME/CFS seem to have.

In all likelihood, it could be some combination of these factors, adding to the frustration of understanding what seems to be a rather complex illness.

The review paper was published in PLOS Pathogens.