Life appears to have recovered faster than we thought after the worst mass extinction event in our planet's history, nicknamed the Great Dying.

New evidence suggests that once the Permian-Triassic extinction hit Earth 252 million years ago, life rebounded in 1 million years - a far cry from the 10 to 20 million years that previous research has indicated.

The extinction event has been linked to a combination of volcanic activity and a runaway greenhouse effect, and was responsible for obliterating 9 in 10 marine species, and 7 in 10 land species.

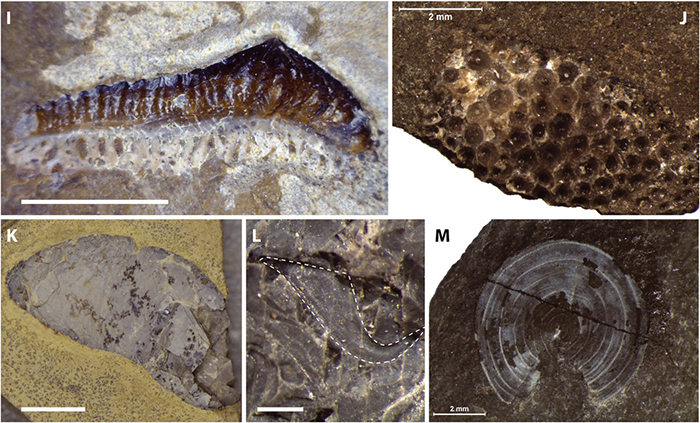

What's prompting the rethink into how life rebounded from all this is a new haul of diverse fossils found in southeastern Idaho, called the Paris Biota, after the nearby city of Paris. The fossils have been dated to 250.6 million years ago - just 1.3 million years after the Great Dying.

A team led by paleontologist Daniel Stephen from Utah Valley University has identified 30 different types of species in the Paris Biota site, including sharks, squid, and starfish, plus some animals that look like nothing we see on Earth today.

Also included in the find are some types of primitive sponges that were thought to have gone extinct hundreds of millions of years before the Great Dying.

While this is only one geographical area, the number of fossils and their diversity suggest life was flourishing as the planet recovered - at least under the sea. The researchers are now assessing other sites to see if more fossils of a similar age can be found.

"To build these diverse ecosystems, you're almost starting from scratch from the mass extinction event," Stephen told The New York Times.

"The information that my colleagues and I have gathered tell us that at least in some places the recovery was relatively rapid."

Some of the fossils in the find. Credit: Brayard et al

Some of the fossils in the find. Credit: Brayard et al

Of course, mass extinction is never a good thing, but at least we now know that organisms can bounce back in a shorter period of time than scientists previously realised.

"There's a handful of places around the world that have this indication of diverse ecosystems," Stephen told Maddie Stone at Gizmodo. "Right now, we're not entirely sure if it was just an isolated phenomenon, or more widespread."

If evidence of the recovery can be found elsewhere too, it's a promising sign for the world today – with so many animals under threat and our own climate shifting. Ideally, we don't want any species to disappear, but this new research suggests life could be tougher to kill than we thought.

"For a lot of us palaeontologists, we look at what's going on in the present day very seriously," Stephen said.

"We see in the fossil record how large these disruptions are - 1.5 million years [to recover] is pretty fast for the geologic record, so perhaps [this study] does offer hope for the planet. But perhaps not so much for us humans."

The findings have been published in Science Advances.