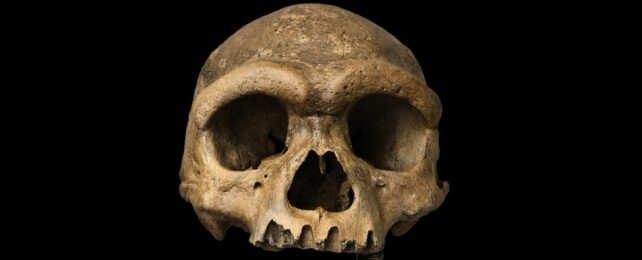

A 146,000-year-old skull known as the 'dragon man', thought to be the sole representative of an ancient human species, actually belongs to a larger group of our extinct relatives, the Denisovans, two new papers claim.

It's the first skull we have from that group, and it was right under our noses for years.

Paleontologist Qiaomei Fu, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, specializes in early modern human settlement in Asia. She led two new studies that reveal the mistaken identity of this skull, using proteins and mitochondrial DNA her team found preserved in the fossil.

The 'dragon man' skull was discovered in the 1930s by a construction worker who was erecting a bridge over the Songhua River in Harbin, China, while the region was under Japanese occupation. The province is known as Longjiang, meaning 'dragon river', hence the skull's nickname.

The bridge builder kept the specimen to himself, hiding it at the bottom of a well. It was only when his family donated it to Hebei GEO University in 2018 that research on this unique find began.

In 2021, the skull was declared a new species of ancient human, Homo longi, but Fu's research rebukes this categorization. That initial description was based on comparative morphology, where paleontologists look at the physical appearance of different fossils to decide where they sit in the family tree.

But morphology can mislead: members of the same species often look very different depending on lifestyle and environment.

Trying to extract fragile molecular evidence from fossils – especially DNA to compare genetic similarity – is often a destructive and patchy task with no guarantee of payoff, but in this case, Fu and her colleagues had astonishing success.

The team was able to retrieve proteins from the skull's petrous bone – one of the densest in the body. They also got hold of mitochondrial DNA (which contains less detail than the DNA stored in a cell nucleus, but is still very useful) from plaque on the dragon man's teeth.

Dental plaque is not widely considered a source of DNA, perhaps because it's the result of a biofilm rather than a direct part of the host's body.

"The finding that the human DNA of the Harbin specimen is better preserved in the dental calculus than in dense bones, including the petrous bone, suggests that dental calculus may be a valuable source for investigating DNA in Middle Pleistocene hominins," Fu and her team write.

These molecules suggest the man is not as unique from other ancient humans as the skull's physical appearance suggests. That's partly because we don't actually have any other complete Denisovan skulls to refer to: until now, they were known only from teeth, one skull fragment, bits of jaw, and a few other body parts.

But the dragon man's mitochondrial DNA reveals a species-level relationship to at least five other Denisovan individuals known from fossil remains found in Siberia. And among the amino acid fragments of 95 proteins found within his skull, four were unmistakably Denisovan, and three were direct matches.

There are limitations to these sampling methods that leave some room for doubt, but Fu and team's findings are enough to place him among the Denisovans for now.

We may have lost a species of ancient human – farewell Homo longi, it was good while it lasted – but it seems we've gained the first ever complete Denisovan skull. Which is pretty wild, given that this missing puzzle piece, a frustrating gap in the paleoanthropologists' catalogue, has actually been in the hands of modern humans for nearly 100 years.

As they say, it's always in the last place you look.