We're not even a month in, and 2016 is already shaping up to be a big year for space exploration. But as we get excited about the future, it's important to reflect on past missions that have led us to this point. And not just the "one giant leap for mankind" success stories, but those that ended in tragedy and taught us so much in the process, such as Apollo 1.

The mission - at the time called Apollo 204 - was going to be the first crewed Apollo mission, with a crew of three: command pilot Virgil I. 'Gus' Grissom, senior pilot Edward H. White II, and pilot Roger B. Chaffee. They were scheduled to take the Apollo Command/Server Module on its first crewed flight into low Earth orbit on 21 February 1967.

But on 27 January 1967, during pre-flight preparations, a fire broke out in the Apollo capsule, killing all three crew-members on board and destroying the command module. It's now been 49 years, and it's still something that's difficult for space lovers to think or talk about.

As devastating as it was, Apollo 1 taught engineers a whole lot about rocket construction and space travel, and highlighted the very real risks and sacrifices taken by those who go into space.

"The investigation into the fatal accident led to major design and engineering changes, making the Apollo spacecraft safer for the coming journeys to the Moon," NASA explained in a tribute to the crew.

Christopher K. Davis/Wikimedia

Christopher K. Davis/Wikimedia

So what happened on board Apollo 1? To begin with, the test was going well. At 1pm on January 27, the Apollo spacecraft was fully assembled and had been stacked on top of the un-fuelled Saturn IB rocket, which was supposed to take it into space.

The cabin had been pressurised with 16.7 pounds per square inch (psi) of 100 percent oxygen, a pressure slightly greater than one atmosphere – just as it would be on launch day – and the crew suited up and went through the full countdown and launch procedure with mission control.

The only notable problem was communication, with static making it nearly impossible for mission control to hear the crew, and vice versa.

But around 6:31pm, the situation quickly began to deteriorate, starting with an increase in oxygen flow and pressure inside the cabin, as Amy Shira Teitel writes for Scientific American:

"The telemetry was accompanied by a garbled transmission that sounded like 'fire'. The official record reflects the communications problem. The transmission was unclear, but the panic was obvious as an astronaut yelled something like 'They're fighting a bad fire – let's get out. Open 'er up.' or 'We've got a bad fire – let's get out. We're burning up.' The static made it impossible to hear the exact words or even distinguish who was speaking."

During that time, flames were visible through the command module's porthole window, and engineers rushed to open the hatch. But because of the pressure within the capsule and the inward opening hatch, the astronauts and outside crew were unable to force it open.

Around 3 seconds after the crew's transmission, the hull ruptured as a result of the pressure. The three astronauts were already dead by the time their bodies were retrieved.

Immediately after the disaster, all crewed flights were suspended while NASA put together the Apollo 204 Accident Review Board, which was overseen by independent government committees. They took the spacecraft apart piece by piece in order to find out what went wrong, and the investigation lasted for the better part of a year.

The investigations concluded that the fire started from a faulty wire below the crew's feet, and spread incredibly quickly due to the fact that the capsule was filled with pure oxygen. According to the reports, it took just 10 seconds for the cabin to fill with flames.

The official cause of death for the crew was smoke inhalation.

The mission went on to be renamed Apollo 1, with the next two Apollo missions - which were un-crewed - being called Apollo 4 and 5. The first successful manned Apollo mission was eventually flown by Apollo 1's back-up crew on Apollo 7 in October 1968.

The tragedy resulted in changes that eventually allowed the Apollo missions to make it to the Moon - a major shift being that capsules were no longer pressurised with 100 percent oxygen before leaving Earth's atmosphere after the Apollo 1 disaster, and instead were filled with a mix of around 34 percent oxygen. On-board materials were also made less flammable, and the hatch was redesigned.

Those lessons have shaped our voyages into space since, and will eventually make it safer for humans to step foot on Mars.

"If we die, we want people to accept it," commander Grissom wrote in his autobiography, Gemini, which was published posthumously in 1968. "We are in a risky business, and we hope that if anything happens to us, it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life."

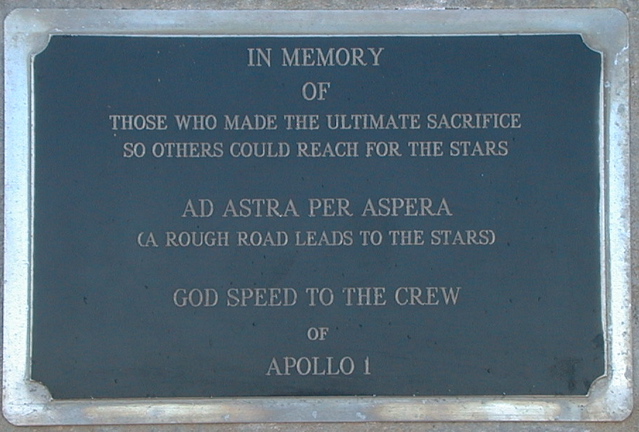

A memorial plaque attached to the now defunct launch pad of Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 34 reads:

"In memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice so others could reach for the stars

Ad astra per aspera (a rough road leads to the stars)

God speed to the crew of Apollo 1″

So thank you, Gus, Edward, and Roger, and all the other men and women who have sacrificed for space exploration. We owe you more than you'll ever know.