A German man remains in remission from HIV an incredible six years after he received a stem cell transplant to treat an aggressive form of leukemia.

The seventh known HIV patient to achieve long-term remission, the patient known as Berlin 2 (B2), received donor stem cells containing only one copy of a mutated gene known to confer resistance to HIV, unlike the two copies present in donor cells given to other patients.

The single-copy cells were thought to provide a short-lived but less durable resistance, raising questions over the precise mechanisms responsible for clearing the immunodeficiency virus from the man's system.

Related: New HIV Prevention Drug Shows 100% Efficacy in Clinical Trial

But the breakthrough, described in a paper led by immunologist Christian Gaebler of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany, offers a tantalising new path towards understanding other ways of potentially curing HIV.

HIV is a particularly tenacious virus that attacks and invades the body's immune cells, dramatically weakening immune defenses and making people vulnerable to other infections. It has a few strategies that make it extremely difficult to treat, including rapid mutation and an ability to evolve drug resistance if therapy isn't maintained perfectly.

HIV exploits a receptor called CCR5 to attach to and enter the host's cells. Once inside, it buries its DNA in the genome. The virus can remain dormant within some long-lived immune cells for years, creating a latent reservoir of the virus in the body.

Reservoirs of HIV are essentially invisible to the immune system and untouched by antiretroviral therapy (ART), the drugs that stop HIV from replicating. If a patient stops taking regular doses of ART, any remaining virus hiding in that reservoir can re-emerge and reignite the infection.

Full stem cell transplants uniquely primed to circumvent these strategies have had a proven record in depleting these reservoirs.

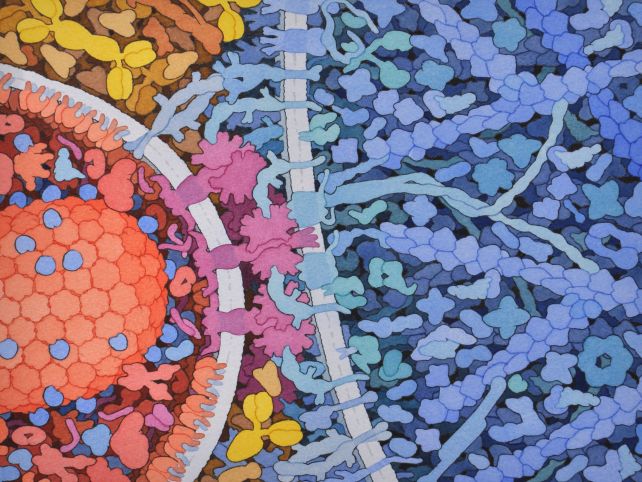

First, the patient undergoes an aggressive course of chemotherapy to wipe out most of their immune system, including a significant number of the cells containing hidden copies of the HIV genome.

Then, a transplant of donor stem cells rebuilds the immune system from scratch. Those new cells can recognize the few remaining HIV hideouts and wipe them out through a phenomenon known as a graft-versus-reservoir response.

In five of the seven known cases of long-term HIV remission – the Berlin, London, Duesseldorf, New York, and City of Hope, California patients – the stem cell donors had two copies of a rare mutation called CCR5 Δ32.

The mutation essentially breaks the CCR5 'keyhole' HIV attaches to, preventing the virus from entering in the first place. With two mutated copies of CCR5 – one inherited from each parent – donated immune cells lack any functioning CCR5 receptors, preventing HIV from unlocking the door and depriving the virus of new places to hide.

B2 already had one copy of the CCR5 Δ32 mutation that he'd inherited from a parent. Nonetheless, he was diagnosed with HIV in 2009 and, after falling ill in 2015, was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia.

Doctors found a matching stem cell donor, though they also had just one copy of the mutation. So B2 underwent chemotherapy and a full stem cell transplant later that year. His condition improved to the point that, in 2018, and against medical advice, he stopped taking ART. This marks the beginning of his remission timeline.

Since then, the virus levels in B2's body have remained undetectable and may even be nonexistent.

The case suggests that double copies of CCR5 Δ32 are not a requirement for durable HIV remission after stem cell treatment, and that the graft-versus-reservoir response may work in other ways.

The suggestion is supported by the sixth patient, a man from Geneva whose stem cell donor lacked the CCR5 Δ32 allele entirely. He stopped taking ART in 2021 and remains in remission at the time of reporting.

However, two patients from Boston who also received stem cell transplants from regular CCR5 donors experienced viral rebound, indicating the need for further investigation to understand what's happening in these cases.

The CCR5 Δ32 stem cell procedure is unlikely to become a standard treatment for HIV patients. Chemotherapy and full stem cell transplant are tough on the body, with a relatively high risk of lifelong health complications and even death.

However, its success could inform treatments that exploit similar mechanisms. The Geneva patient and B2's cases are exciting because they shift the focus away from finding rare unicorn donors to the question of how to replicate reservoir reduction, partial CCR5 protection, and graft-versus-reservoir responses.

These may all be achievable through pharmaceutical treatments and gene editing, and research is already underway to that effect.

"Overall, the case of the second Berlin patient B2 suggests that significant reductions of persistent reservoirs can lead to HIV cure independent of homozygous CCR5Δ32-mediated viral resistance," the researchers write in their paper.

"This underscores the critical importance of modulating and potentially eliminating the HIV reservoir in strategies aimed at long-term remission and cure."

The results have been published in Nature.