A build-up of meltwater under the Greenland ice sheet in 2014 resulted in a flood of such magnitude that it burst upward through tens of meters of solid ice, fracturing the surface and spilling water to the open air.

It's the first time scientists have documented this phenomenon in Greenland, and it gives us new information for understanding how Greenland is going to change as the ice sheet continues to melt away into the sea.

It also shows just how powerful and destructive meltwater lurking under the ice sheet can be.

"The existence of subglacial lakes beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet is still a relatively recent discovery, and – as our study shows – there is still much we don't know about how they evolve and how they can impact on the ice sheet system," explains glaciologist Jade Bowling of Lancaster University in the UK.

"Importantly, our work demonstrates the need to better understand how often they drain, and, critically, what the consequences are for the surrounding ice sheet."

Related: Mysterious 'Dark River' May Flow For 1,000 Kilometres Below Greenland, Scientists Say

Greenland's ice sheet is a large body of ice that covers most of the island, with a maximum thickness of more than 3 kilometers (1.9 miles). This frozen expanse locks up a vast amount of water; were it to melt away entirely, global sea levels would rise by an estimated 7.4 meters (24 feet).

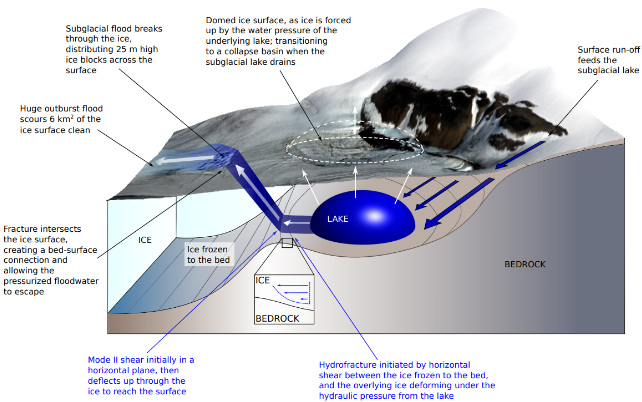

It's only recently that scientists have been able to see what's under the ice, using aircraft equipped with radar to image its depths. Those observations reveal an environment that is complex and dynamic. Not only are liquid lakes prevalent under the ice sheet, they ebb and flow with meltwater, sometimes causing the ice to buckle upwards in a phenomenon known as 'water blisters'.

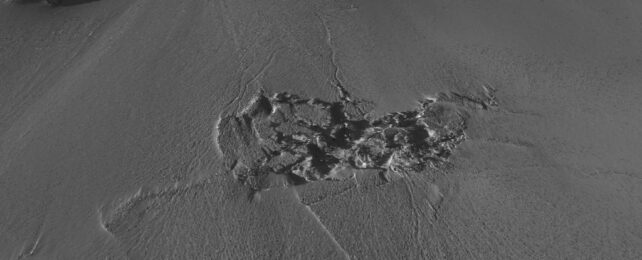

A flood so powerful that it can crack the ice is something new. Bowling and her colleagues discovered evidence of this wild event when they studied satellite data from 2014. Over a 10-day period in late July to early August, they noticed that an area spanning 2 square kilometers suddenly dropped in elevation by a whopping 85 meters – the height of a medium-sized skyscraper.

Prior to this collapse, the area had been rising in elevation by about 10 to 15 meters as water pushed it upwards into a dome. It collapsed when the water suddenly drained out – about 90 million cubic meters worth of it.

Approximately 1 kilometer downstream from the basin, the researchers found more oddities. There, a large area of the ice had become heavily fractured, and large ice boulders up to 25 meters high were deposited on the surface. Further downstream, a 6-square-kilometer area of the ice sheet surface had been scoured clean.

"When we first saw this, because it was so unexpected, we thought there was an issue with our data," Bowling explains. "However, as we went deeper into our analysis, it became clear that what we were observing was the aftermath of a huge flood of water escaping from underneath the ice."

The fracture zone downstream from the basin is the point, the researchers say, at which the water burst forth from under the ice, gushing out and washing clean a huge area as it flowed across the surface.

While previous observations have shown that meltwater can move around under the ice, this is the first time we've seen evidence of it punching clean through. As Greenland continues to melt at a high rate, this is important information to have.

"What we have found in this study surprised us in many ways. It has taught us new and unexpected things about the way that ice sheets can respond to extreme inputs of surface meltwater, and emphasised the need to better understand the ice sheet's complex hydrological system, both now and in the future," says glaciologist Amber Leeson of Lancaster University.

"Given the control that subglacial hydrology has on the dynamics of the ice sheet, it is critical that we continue to improve our understanding of these hidden, and poorly understood, hydrological processes, and these satellite observations are key to that."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.