Recently discovered stone tools and circular structures on the Isle of Skye suggest humans from the Old Stone Age traveled all the way to the frigid northwest edge of Scotland.

This boundary-pushing endeavor took early humans in northern Europe to the "far end of everything", according to a new paper from an international team of archaeologists.

"This is a hugely significant discovery which offers a new perspective on the earliest human occupation yet known, of north-west Scotland," says lead author and archaeologist Karen Hardy from the University of Glasgow.

"The journey made by these pioneering people who left their lowland territories in mainland Europe to travel northwards into the unknown is the ultimate adventure story."

Until recently, there hadn't been any clear evidence of a human population in Scotland before the Holocene, the current geological epoch that began about 11,700 years ago. Even when earlier artifacts began to pop up, it was assumed that the inhospitable climate would have only allowed for visiting humans, not a sustained population.

But the new study suggests humans arrived – and settled – earlier than we give them credit for.

Hardy and colleagues have based their conclusions on a collection of stone tools and circle structures found on the Isle of Skye in the last eight years.

Unfortunately, no radiocarbon-datable material has been recovered, so the exact timing of human arrival is unknown. Still, there are some important clues in the details.

The ancient baked mudstone tools found on Skye have complex features that resemble artifacts from continental Europe in the Late Upper Paleolithic, specifically those of Ahrensburg culture, argue Hardy and colleagues.

Ahrensburg-like tools have been found on some other isles and islands in Scotland, but never this far north and never in such abundance.

The number of artifacts made from local materials on Skye "indicate either a reasonably sized population or long-term occupation", the team of archaeologists argue.

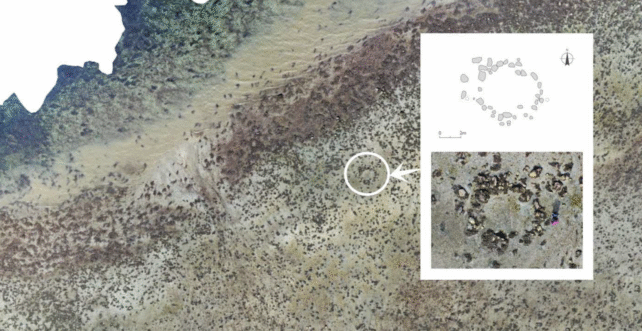

What's more, archeologists have uncovered several stone circles, between 3 and 5 meters (10 and 16 feet) in diameter, in a large tidal flat in the center of the Isle. Long ago, when Scotland was icier, this tidal flat would have existed above sea level.

Today, the stone circles are only visible for around two to three hours per year, when the extreme spring tides arrive. At other times, archaeologists have had to snorkel.

Even during the lowest tide, digging into the waterlogged sandy bottom made it very difficult to measure definitive sediment layers for dating.

Based on some climate modeling, however, this tidal flat was above sea level roughly 11,000 years ago. For the last 10,000 years, the sites of the stone circles have been covered by water, meaning they were most likely built before then.

What's more, other similar stone circles, found across the sea in Norway, were radiocarbon-dated to between roughly 10,400 and 11,000 years ago.

"The similarity between these circular alignments and those at Sconser is remarkable and supports the interpretation of a Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene age," write Hardy and colleagues.

Experts disagree on when the Ahrensburg culture came and went, but some studies suggest it existed as recently as 10,500 years ago. There is also evidence of Ahrensburgian-like artifacts from this time in what is now southern England.

Today, the Isle of Skye is connected to the mainland by a human-made bridge. During the Upper Paleolithic, however, when ice sheets in the region were expanding, there may have been a land bridge or very narrow crossing, less than 300 meters wide. This could have been walkable to Old Stone Age humans during spring tides.

During this time, however, the western margins of Scotland would have been cold and inhospitable. The authors of the recent archaeological analysis suspect the earliest humans came to Skye after the ice sheets had already begun to recede.

"As they journeyed northwards, most likely following animal herds, they eventually reached Scotland, where the western landscape was dramatically changing as glaciers melted and the land rebounded as it recovered from the weight of the ice," hypothesizes Hardy.

"A good example of the volatility they would have encountered can be found in Glen Roy, where the world-famous Parallel Roads provide physical testament to the huge landscape changes and cataclysmic floods that they would have encountered, as they travelled across Scotland."

Without reliable radiocarbon dating it's hard to say much about when these cultures arrived. Hardy and colleagues admit this is a limitation, but based on what we know about Old Stone Age humans in continental Europe and in southern England, there's reason to suspect an early push northward.

The study was published in The Journal of Quaternary Science.