A supermassive black hole around a million times the mass of the Sun just gave away its position in spectacular fashion.

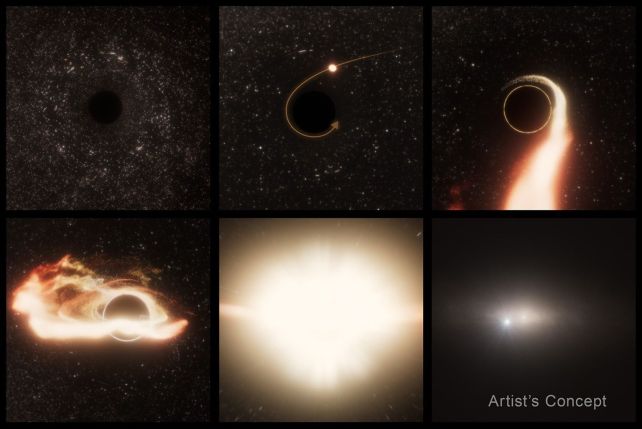

When a passing star veered a little too close, it was torn apart in the black hole's gravitational field, releasing an enormous flare of light.

That flare of light, a tidal disruption event recorded by telescopes on Earth, was named AT2024tvd, and its detection revealed something very peculiar about the galaxy 600 million light-years away in which the event took place.

The black hole responsible, according to a team of astronomers led by Yuhan Yao of the University of California, Berkeley, is a wanderer, untethered from the nucleus of a galaxy. It is not even in a binary orbit with the supermassive black hole that is at the heart of the host galaxy.

"AT2024tvd is the first offset tidal disruption event (TDE) captured by optical sky surveys, and it opens up the entire possibility of uncovering this elusive population of wandering black holes with future sky surveys," Yao says.

"Right now, theorists haven't given much attention to offset TDEs. I think this discovery will motivate scientists to look for more examples of this type of event."

Black holes, when they're just lurking around in space, are very difficult to spot, especially in other galaxies. They don't emit any radiation we can currently detect, and that's our main tool for studying the cosmos. We can detect black hole pairs by way of gravitational waves when they smack into each other, but a lone black hole doing nothing is invisible.

There's an exception. When something gets close enough, the powerful tidal forces within the black hole's gravity field will rip it apart, and send it spiraling down beyond the event horizon. This process, known as a tidal disruption, emits a blazing flare of light across the electromagnetic spectrum that we can detect from millions to billions of light-years away, and deconstruct to learn about the black hole responsible.

AT2024tvd was just such a flare, first detected on 25 August 2024 by the Zwicky Transient Facility, a wide-field sky survey designed to pick up transient events like supernovae and TDEs. Astronomers rapidly followed up, using radio, optical, and X-ray telescopes to capture as much of the event's light as possible.

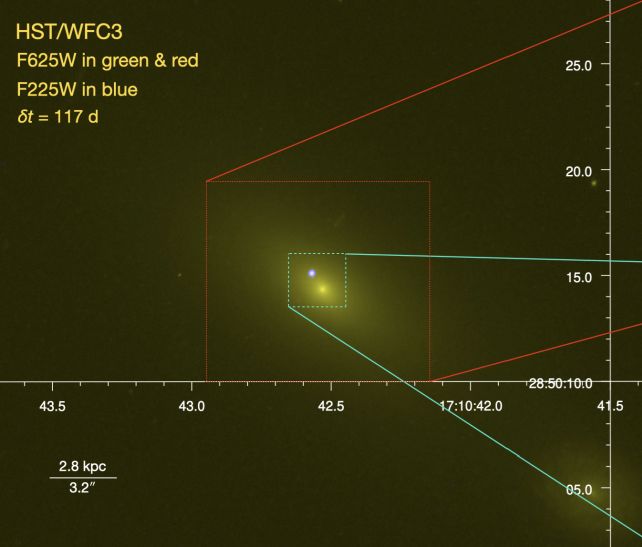

Yao and colleagues were able to trace the event to a point in the sky 600 light-years away, where, conveniently, a large galaxy can also be found. But, although their analysis revealed a supermassive black hole as the culprit for the TDE with a mass between 100,000 and 10 million Suns, the point in the galaxy from which the flare originated was not the galactic center.

This is really interesting. Supermassive black holes are usually found sitting in the centers of galaxies – the gravitational hub around which the entire kit and kaboodle revolves. AT2024tvd's host galaxy, however, already has a supermassive black hole in its center, one that's around 100 million solar masses.

Now, there are galactic centers that have two or more supermassive black holes, locked in a gravitational dance that will one day see them merge to form one even huger black hole.

However, the two supermassive black holes in the galaxy in question are not gravitationally bound in a binary. They're separated by a distance of around 2,600 light-years, and the smaller one is just moseying about the galactic bulge.

Galaxies gain extra supermassive black holes when they collide with other galaxies; over time, the two supermassive black holes at their hearts find each other, which is when we see them locked together as a system.

The presence of a second supermassive black hole in this particular galaxy means that, at some point in its past, it merged with another galaxy.

What we don't know is whether it's on its way into or out of the galactic center. It's entirely possible that the center already hosts a binary. If this is the case, then the third black hole may have once been among them, and was booted out by a three-body interaction.

Or we could just have caught it on an inbound trajectory on its way to the center, where it will enter a binary interaction with the black hole already therein. Either scenario is possible.

One way to learn more about this black hole configuration is to find more galaxies that have similarly offset rogue supermassive black holes. This research, the team says, offers a potential pathway to do so.

"Tidal disruption events hold great promise for illuminating the presence of massive black holes that we would otherwise not be able to detect," says astronomer Ryan Chornock of UC Berkeley. "Theorists have predicted that a population of massive black holes located away from the centers of galaxies must exist, but now we can use TDEs to find them."

The research has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and is available on arXiv.