A deep-sea expedition to one of Earth's most remote island chains has surfaced stunning pictures of the vibrant ecosystems surrounding hydrothermal vents that scientists didn't even know were there.

The 35-day journey aboard Schmidt Ocean Institute's Falkor (too) research vessel was part of the Ocean Census's race to document marine life before it is lost to threats like climate change and deep sea mining.

This expedition took an international team of scientists to the South Sandwich Islands, in the South Atlantic near Antarctica, which boasts the Southern Ocean's deepest trench.

Despite facing subsea earthquakes, hurricane-force winds, towering waves, and icebergs, the crew was rewarded with a trove of incredible new discoveries.

You might have already watched the expedition's world-first footage of a live colossal squid, but some of their other finds deserve a moment in the spotlight.

Like this vermillion coral garden thriving on Humpback Seamount, near the region's shallowest hydrothermal vents at around 700 meters deep (nearly 2,300 feet).

The tallest vent chimney stood four meters (13 feet) tall, proudly sporting an array of life, including barnacles and sea snails. Like drones in a New Year's Eve sky, a fleet of shrimp whizzed round these submarine skyscrapers.

These hydrothermal vents, on the northeast side of Quest Caldera, are the only South Sandwich Island vents explored via remotely operated vehicle (ROV) thus far; we can't wait to see what future expeditions uncover.

"Discovering these hydrothermal vents was a magical moment, as they have never been seen here before," says hydrographer Jenny Gales from the University of Plymouth in the UK.

But certain specimens deserve a close-up: like this exquisite nudibranch, unspecified, which blackwater photographer Jialing Cai snapped at 268 meters deep in the near-freezing waters east of Montagu Island.

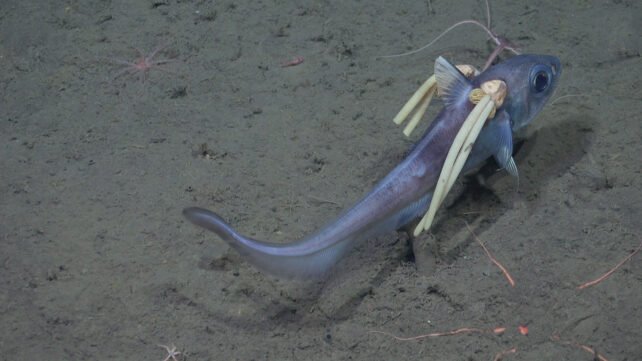

Nearby, a slightly more upsetting moment was captured: a grenadier fish with parasitic copepods – likely Lophoura szidati – tucked into its gills like horrid pigtails.

And this stout little sea cucumber, recorded 650 metres below the sea surface at Saunders East, with a gob full of what we will informally dub a deep-sea puffball.

Now, brace yourself for the first ever image of Akarotaxis aff. gouldae, a species of dragonfish that has evaded our cameras for two years since its discovery.

Something else that nobody's seen before? Snailfish eggs on a black coral. Not even marine biologists knew this was a thing, until now.

"This expedition has given us a glimpse into one of the most remote and biologically rich parts of our ocean," says marine biologist Michelle Taylor, the Ocean Census project's head of science.

"This is exactly why the Ocean Census exists – to accelerate our understanding of ocean life before it's too late. The 35 days at sea were an exciting rollercoaster of scientific discovery, the implications of which will be felt for many years to come as discoveries filter into management action."

Look behind-the-scenes aboard the Falkor (too) research vessel here.