Surgeons at Duke University have resuscitated a 'dead' heart on the operating table after it stopped beating for more than five minutes.

The organ was later transplanted into the chest of a three-month-old child, saving their life.

The infant with the donor heart continued to show normal cardiac function and no signs of organ rejection at six months of age, according to a brief report.

Related: Eerie Personality Changes Sometimes Happen After Organ Transplants

The story is proof that the concept of 'on-table reanimation' works at preserving hearts for transplantation – at least for infants.

With the consent of the donor family, surgeons reinvigorated a small donor heart on the operating table using an oxygenator, a centrifugal pump, and a hanging reservoir to collect expelled blood.

This contraption had to be custom-designed, as current care systems that keep organs alive outside of bodies are too big for infant hearts.

Today in the United States, up to 20 percent of infants in need will die waiting for a heart.

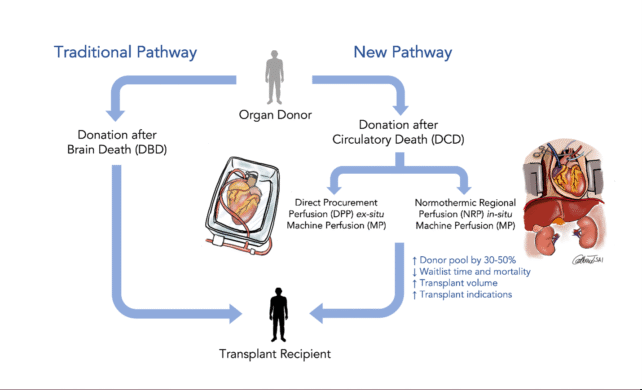

Most organ donors must be declared brain dead before donation. Only 0.5 percent of pediatric heart transplants are donated after circulatory death, when the heart stops beating and blood stops circulating.

Some critics do not think it is morally correct to take a terminal patient off life support, get their heart beating again, and then remove it for transplantation. Concerns arise over declarations of death, and how to reanimate organs in an ethical way.

After circulatory death, donor hearts can be re-oxygenated while they are still in the donor body, or they can be resuscitated on the operating table using machines.

Critics argue that if a heart is reanimated in a donor's body, it negates the very definition of circulatory death.

Proponents of 'on-table' reanimation, like surgeons at Duke, argue that working outside of a donor's body reduces ethical concerns. They also note that using organs after circulatory death has the potential to increase the donor pool by up to 30 percent.

Another team of surgeons at Vanderbilt University has a different idea. They have devised a way to avoid the most common ethical concerns.

Their technique doesn't seek to immediately reanimate donor hearts; instead, it preserves them.

In a recent brief report, the team explains that with an aorta clamp and a cold-preserving flush of liquid, they successfully recovered three donor hearts for transplantation.

By clamping off the heart's circulatory system, the team kept their work separate from the donor's brain (which raises ethical concerns over resuscitation).

"Our technique flushes oxygenated preservation solution to the donor heart only, without reanimation of the heart and without systemic or brain perfusion," explain the team.

In initial surgeries, the technique showed "excellent early postoperative outcomes".

All three donor hearts were successfully transplanted with healthy function.

"This method of heart recovery offers the possibility of broad application," the Vanderbilt surgeons conclude.

The Duke and Vanderbilt reports were both published in NEJM.