Not content with a diet of old leaves, some worm species actually eat bones. A new study has now traced the ancient ancestors of these bone-burrowers back through 100 million years of evolution.

Deep in the ocean, bone-eating worms from the genus Osedax feast on the carcasses of whales, sucking up fats and proteins from the skeletons. And it looks like they've been doing so for a while now.

By scanning fossils to look for traces of bone-eating behavior, researchers from University College London (UCL) and the Natural History Museum in the UK have been able to identify seven new types of worm from the Cretaceous period.

There would've been no whale on the menu at that time, but traces left behind by these worms were found in fossils of mosasaurs, ichthyosaurs, and plesiosaurs: the dominant marine reptiles of the time, now on show in museum exhibits.

Related: 'Giant' Predator Worm That Ruled Ancient Oceans Discovered in Greenland

"We haven't found anything else that makes a similar burrow to these animals," says paleontologist Sarah Jamison-Todd, from UCL. "As the ancient bores are so similar to modern Osedax species, and we don't have body fossils to contradict us, we assume that they were made by the same or a similar organism."

"It shows that the bone-eating worms are part of a lineage that stretches back at least to the Cretaceous, and perhaps further. We can see how the diversity of bone-eating worms changes across millions of years."

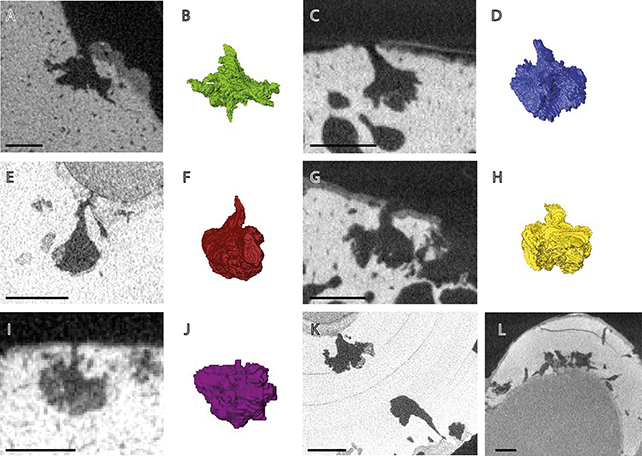

The team was able to build 3D models of 130 fossils without damaging them, through the use of computed tomography (CT) scans. Six fossils showed signs of burrows.

That then led to the identification of seven new ichnospecies – species categorized based on traces in fossils, rather than direct remains of the creatures. Some of the boring patterns matched modern-day species, suggesting a surprising level of evolutionary stability across many millions of years.

The researchers also used microscopic fragments around the fossils to date the bones and the worms that chewed through them. That placed them at at least 100 million years ago, meaning these creatures evolved much earlier than previously thought.

"By using the remains of small organisms that make up the chalk itself, we were able to date the fossils to more precise time slices of the Cretaceous period," says Marc Jones, paleontologist at the Natural History Museum.

There are plenty of other discoveries like this still waiting to be made, the researchers suggest – which could happen through further scans of ancient fossils as well as studies of the modern species living in the oceans today.

Additional work looking at the genetics of the organisms living today could tell us more about the evolutionary history of these tiny creatures, though researchers will have to collect more samples and more data first.

"There are many more examples of boring that haven't yet been named from both ancient and modern bone-eating worms," says Jamison-Todd. "In fact, some bores from the Cretaceous appear to be similar to ones that are still made today."

"Finding out whether these burrows are made by the same species, or are an example of convergent evolution, will give us a much better idea of how these animals have evolved, and how they have shaped marine ecosystems over millions of years."

The research has been published in PLOS ONE.