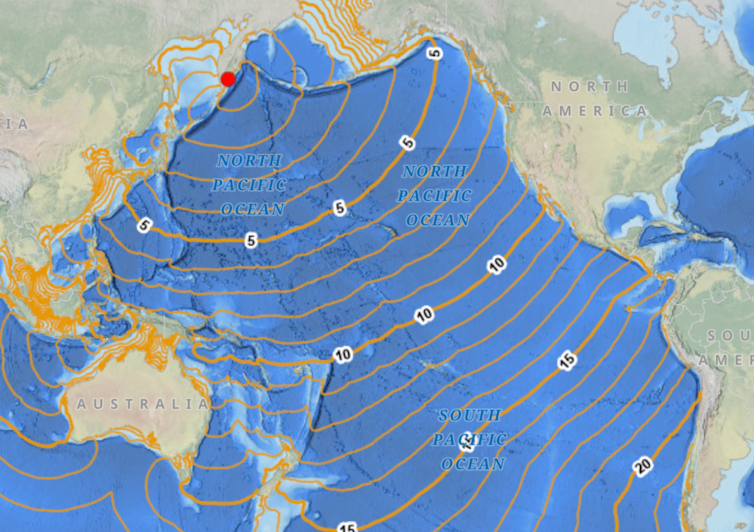

One of the ten largest earthquakes ever recorded just struck Kamchatka, the sparsely populated Russian peninsula facing the Pacific. The magnitude 8.8 quake had its epicentre in the sea just off the Kamchatka coast.

Huge quakes such as these can cause devastating tsunamis. It's no surprise this quake has triggered mass evacuations in Russia, Japan and Hawaii.

But despite the enormous strength of the quake, the waves expected from the resulting tsunami are projected to be remarkably small. Four metre-high waves have been reported in Russia.

Related: Scientific First: 'Slow-Motion' Earthquakes Captured in Real Time

But the waves are projected to be far smaller elsewhere, ranging from 30 centimetres to 1 metre in China, and between 1 and 3 metres in parts of Japan, Hawaii and the Solomon Islands, as well as Ecuador and Chile on the other side of the Pacific.

So why have authorities in Japan and parts of the United States announced evacuation orders? For one thing, tsunami waves can suddenly escalate, and even the smaller tsunami waves can pack surprising force. But the main reason is that late evacuation orders can cause panic and chaos. It's far better to err on the side of caution.

Too early is far better than too late

When tsunami monitoring centres issue early warnings about waves, there's often a wide range given. That represents the significant uncertainty about what the final wave size will be.

As earthquake scientists Judith Hubbard and Kyle Bradley write:

the actual wave height at the shore depends on the specific bathymetry [underwater topography] of the ocean floor and shape of the coastline. Furthermore, how that wave impacts the coast depends on the topography on land. Do not second-guess a tsunami warning: evacuate to higher ground and wait for the all-clear.

If the decision was left to ordinary people to decide whether to evacuate, many might look at the projected wave heights and think "what's the problem?". This is why evacuation is usually a job for experts.

Behavioural scientists have found people are more likely to follow evacuation advice if they perceive the risk is real, if they trust the authorities and if there are social cues such as friends, family or neighbours evacuating.

If evacuations are done well, authorities will direct people down safe roads to shelters or safe zones located high enough above the ocean.

When people outside official evacuation zones flee on their own, this is known as a shadow evacuation. It often happens when people misunderstand warnings, don't trust official boundaries, or feel safer leaving "just in case".

While understandable, shadow evacuations can overload roads, clog evacuation routes, and strain shelters and resources intended for those at greatest risk.

Vulnerable groups such as older people and those with a disability often evacuate more slowly or not at all, putting them at much greater risk.

In wealthy nations such as Japan where tsunamis are a regular threat, drills and risk education have made evacuations run more smoothly and get more people to evacuate.

Japan also has designated vertical shelters – buildings to which people can flee – as well as coastal sirens and signs pointing to tsunami "safe zones".

By contrast, most developing nations affected by tsunamis don't have these systems or infrastructure in place. Death tolls are inevitably higher as a result.

More accurate warnings, fewer false alarms

A false alarm occurs when a tsunami warning is issued, but no hazardous waves arrive. False alarms often stem from the need to act fast. Because tsunamis can reach coastlines within minutes of an undersea earthquake, early warnings are based on limited and imprecise data — mainly the quake's location and magnitude — before the tsunami's actual size or impact is known.

In the past, tsunami alerts were issued using worst-case estimates based on simple tables linking quake size and location to fixed alert levels. These did not account for complex uncertainties in how the seafloor moved or how energy translated into how much water was displaced.

Even when waves are small at sea, they can behave unpredictably near shore. Tide gauge readings are easily distorted by nearby bays, seafloor shape and water depth. This approach often came at the cost of frequent false alarms.

A stark example came in 1986, when Hawaii undertook a major evacuation following an earthquake off the Aleutian Islands. While the tsunami did arrive on time, the waves didn't cause any flooding. The evacuation triggered massive gridlock, halted businesses and cost the state an estimated A$63 million.

In 1987, the United States launched the DART program. This network of deep-sea buoys across the Pacific and, later, globally, measure changes in ocean pressure in real time, allowing scientists to verify whether a tsunami has actually been generated and to estimate its size far more accurately.

When there's a tsunami false alarm, it makes people more sceptical of evacuation orders and compliance drops. Some people want to see the threat with their own eyes. But this delays action – and heightens the danger.

Shifting from simple tables and inferences to observational data has significantly reduced false alarms and improved public confidence. Today's tsunami warnings combine quake analysis with real-time ocean data.

What have we learned from past tsunamis?

In 2004, a huge 9.1 magnitude earthquake off the coast of Aceh in Indonesia triggered the Indian Ocean tsunami, the deadliest in recorded history. Waves up to 30 metres high inundated entire cities and towns.

More than 227,000 people died throughout the region, primarily in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and Thailand. All these countries had low tsunami preparedness. At the time, there were no tsunami warning systems in the Indian Ocean.

The even stronger 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan killed just under 20,000 people. It was a terrible toll, but far fewer than the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Evacuations took place and many people got to higher ground or into a high building.

In 2018, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake hit central Sulawesi in Indonesia, triggering tsunami waves up to 7 metres high. Citizen disbelief and a lack of clear communication meant many people did not evacuate in time. More than 4,000 people died.

These examples show the importance of warning systems and evacuations. But they also show their limitations. Even with warning systems in place, major loss of life can still ensue due to public scepticism and communication failures.

What should people do?

At their worst, tsunamis can devastate swathes of coastline and kill hundreds of thousands of people. They should not be underestimated.

If authorities issue an evacuation order, it is absolutely worth following. It's far better to evacuate early and find a safe space in an orderly way, than to leave it too late and try to escape a city or town amid traffic jams, flooded roads and and widespread disruption.![]()

Milad Haghani, Associate Professor and Principal Fellow in Urban Risk and Resilience, The University of Melbourne and Zahra Shahhoseini, Research Fellow in Public Health, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.