A woman who lived and died 2,000 years ago in the Altai Mountains of Siberia is opening a new window into ancient tattoos.

A careful analysis of her mummified remains didn't just reveal tattooed figures across both hands and forearms, but the method whereby they were applied. These adornments, says a team of researchers led by Gino Caspari from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the University of Bern in Germany, are some of the most elaborate ever seen from the Pazyryk culture to which she belonged.

"The tattoos of the Pazyryk culture – Iron Age pastoralists of the Altai Mountains – have long intrigued archaeologists due to their elaborate figural designs," Caspari says.

"Prior scholarship focused primarily on the stylistic and symbolic dimensions of these tattoos, with data derived largely from hand-drawn reconstructions. These interpretations lacked clarity regarding the techniques and tools used, and did not focus much on the individuals but rather the overarching social context."

Related: Artist Tattooed Himself to Solve Mystery of Ötzi The Iceman's Tattoos

Humanity has a rich and fascinating history of tattooing, from the sacred to the purely decorative to the downright odd. It's also likely that our ancestors practised it heavily, with evidence of the artform emerging across many ancient cultures dating back thousands of years.

With a scarcity of preserved tattooing instruments, mummified skin often serves as the only record of the craft. Even then, the designs aren't always easy to see, since mummification hardens and darkens the skin significantly. This has made ancient tattoos somewhat difficult to study.

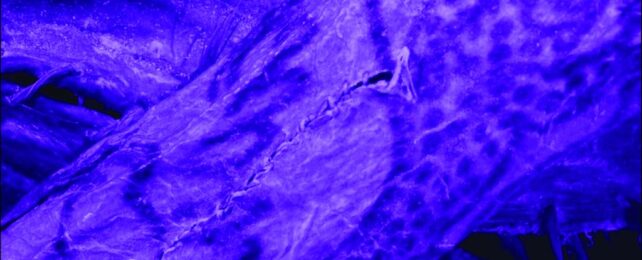

In recent years, however, new imaging techniques have emerged; infrared and near-infrared photography reveals tattoos on mummified skin that may have been obscured in optical wavelengths, and laser-stimulated fluorescence reveals where ink has been deposited in the skin.

Caspari and his colleagues turned to cutting-edge infrared photography to image in three dimensions the tattoos on the arms and hands of their unnamed Pazyryk woman, who was about 50 years old when she died. Then, they reconstructed the designs, and investigated how the tattoos were made.

To do so, the team included archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf of the Tennessee Division of Archaeology, and tattoo artist Danny Riday of Ancestral Arts tattoo boutique in France. In previous research led by Deter-Wolf, Riday tattooed himself using a variety of historical techniques to create a living dictionary of tattoo marks against which to compare mummified remains.

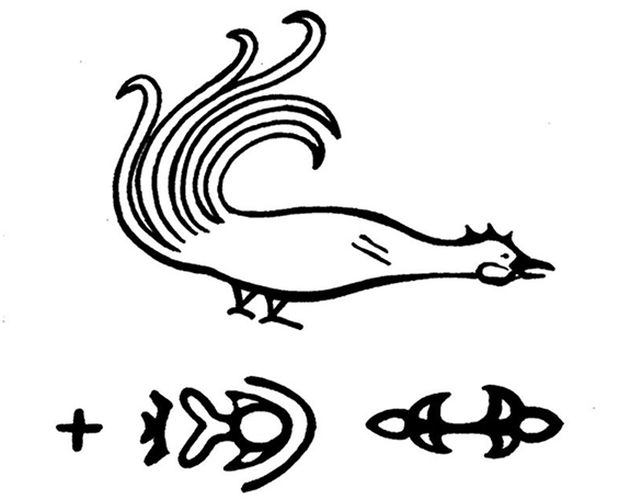

Their new findings revealed not only that different types of tools were used, but that different skill levels can be observed between the woman's hands and arms. On her hands, relatively simple images appear. On her right hand is a floral pattern; on her left, a cross, a floral or fish-like pattern, and a bird that looks like a rooster on her thumb.

On her left forearm, a moose or elk-like animal is being attacked by a creature that resembles a gryphon. On her right forearm appears the most elaborate tattoo of all: two antlered ungulates, locked in a life-or-death struggle with two tigers and a leopard.

The images were all hand-poked; the larger pieces created using a multi-point tool and then finished off with a separate, finer tool, likely with just one point, to achieve the narrower lines. A similar tool was probably used for the smaller motifs on her hands.

The forearm tattoos required a greater level of skill than the tattoos on the hand – suggestive, perhaps, of either multiple artists, or a single artist whose techniques improved over time.

"It was Danny's expertise that allowed us to evaluate the differences between the forearm tattoos, and describe the likely tools," Deter-Wolf told ScienceAlert.

"This study provides the first positive evidence that the Pazyryk tattoos were created by hand poking, and establishes the use of multiple tool types. It also reiterates the ability of Pazyryk tattooers, and establishes them as skilled craftspeople comparable to the Iron Age artisans who created Scythian textiles, wood, leather, and metal work."

These results suggest that tattooing was no idle pastime for the Pazyryk people, but an important part of the culture that called for skilled artists that honed their craft over time much like modern tattoo artists do.

This is reinforced by one key detail seen in this mummy and the other six tattooed mummies from the same region in the early Iron Age: none of the tattoos overlap, and many of them are perfectly placed for the part of the body on which they were inscribed. It suggests that the placement of tattoos was thought-out and very intentional, and thus an important part of Pazyryk culture.

"The study offers a new way to recognize personal agency in prehistoric body modification practices. Tattooing emerges not merely as symbolic decoration but as a specialized craft – one that demanded technical skill, aesthetic sensitivity, and formal training or apprenticeship," Caspari says.

"This made me feel like we were much closer to seeing the people behind the art, how they worked and learned and made mistakes. The images came alive."

The research has been published in Antiquity.