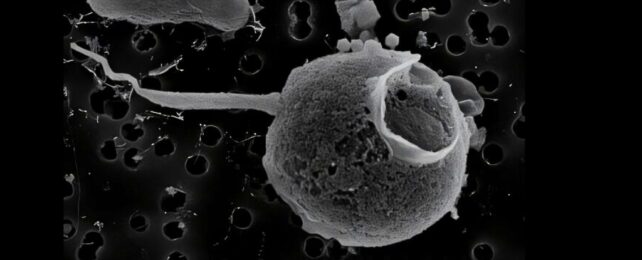

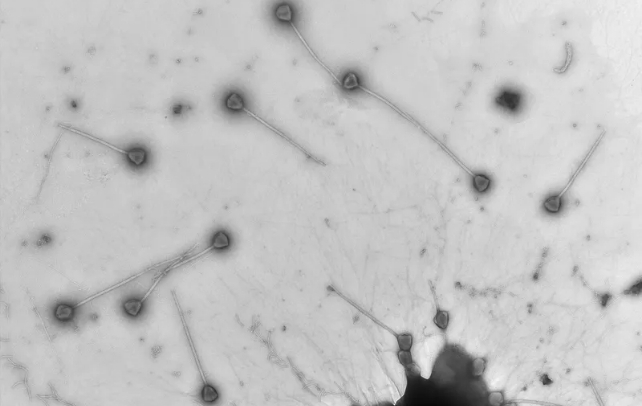

A viral particle with an unprecedentedly long 'tail' has been caught infecting dinoflagellate plankton in the Pacific Ocean.

The virus, PelV-1 uses its tail to attach to its intended victim while shunting its genetic material inside. In addition, Cornell University oceanographer Andrian Gajigan and colleagues suspect that this impressive appendage may also help the virus find its sometimes sparsely located Pelagodinium plankton hosts, which float in the upper layers of the vast, open ocean.

Related: Strange Cellular Entity Challenges Very Definition of Life Itself

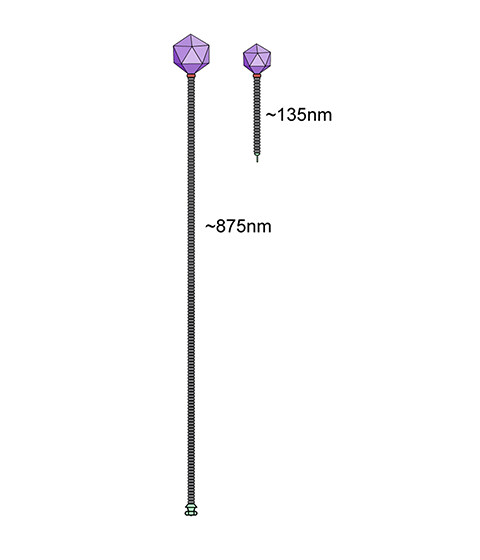

While most virus tails are measured in nanometers, this one reaches a staggering 2.3 micrometers.

"This tail is longer than that seen on any other virus, exceeding the ~875 nm tail of the longest phage, P74-26 infecting Thermus thermophilus and another giant virus, Tupanvirus (tail at 0.55 - 1.85 µm)," Gajigan and team write in their paper, which is not yet peer reviewed.

Yet, the ratio between PelV-1's 'tail' and 'head' is the same as in P74-26.

"Whether this is coincidental or whether some underlying mechanism constrains this ratio regardless of taxa is unknown," the researchers note.

Since giant viruses were first discovered in 2003, they have presented us with plenty of surprises: some are larger than bacteria, others hold secrets about our own cellular structures, and some challenge the line between living and inanimate entities.

Dinoflagellates play a massive role in our ecosystem, contributing to Earth's oxygen as well as cycling many other nutrients, including carbon, around the planet. They can also cause harmful algal blooms, which significantly impact our waterways and those that rely on them, from wildlife to fisheries.

But "how viruses influence dinoflagellate ecology remains little known," the team explains.

Very few viruses have been isolated from planktons so far, so there are surely many more oddities to discover.

The research has been uploaded ahead of peer review on bioRxiv.