A baby born in the US has made headlines for a surprising reason: they came from an embryo that had been frozen for more than 30 years – setting a new world record.

The embryo was created and stored in 1994, back when Bill Clinton was US president and the internet, email and mobile phones were still in their infancy.

Now, decades later, that embryo has become a living child. But how is this possible – and what does it mean for the future of fertility treatment?

Related: 'World's Oldest Baby' Born From 30-Year-Old Frozen Embryo

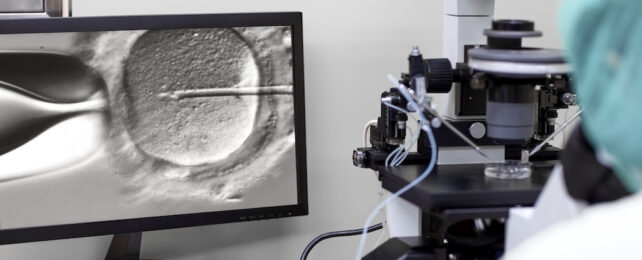

Freezing embryos is a common and effective part of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). During IVF, multiple eggs are fertilised, and any unused embryos can be frozen and stored for future use. Globally, thousands of embryos are placed in long-term storage each year – and as the demand for fertility treatment grows, so too does the number of embryos in storage.

But once a person or couple finishes treatment, the question of what to do with unused embryos can become complicated. As this case in the US illustrates, families and circumstances change.

Relationships may end. People may change their minds. And yet, many feel conflicted about allowing embryos to "perish" (the term used when frozen embryos are removed from storage, thawed and not used), especially after investing significant emotional, physical and financial resources in their creation.

As a result, many continue to pay storage fees for years – sometimes decades – after their treatment has ended.

Embryo donation

One option for those with unused embryos is to donate them. Typically, this is coordinated through the fertility clinic.

But in this record-breaking case, the embryos were donated through a US Christian organisation called Snowflakes, which allows donors to choose the recipients.

The donor – now a woman in her 60s – wanted a say in where the embryos went because any resulting children would be full genetic siblings to her 30-year-old daughter. In many countries, donor-conceived people are now entitled to information about their donors.

But rarely does this involve embryos frozen for decades – raising the possibility of a future connection between the child, their parents and the donor family, including a half-sibling born 30 years earlier.

In the US, there's no legal limit on how long embryos (or sperm and eggs) can be stored. In the UK, the maximum storage limit was recently extended to 55 years, enabling a similar situation: someone could be conceived from an embryo stored for decades, and the donor may be elderly – or even deceased – by the time contact is made.

What remains unclear is how these wide age gaps between donor and child – or between donor-conceived siblings – might affect how people relate to one another. It's an area that remains largely unexplored.

Finding genetic relatives

As direct-to-consumer DNA testing becomes increasingly common, more donor-conceived people are turning to services like 23andMe and Ancestry.com to find genetic relatives outside of regulated routes. These commercial tests allow users to upload a sample and receive a list of people they may be related to, including potential donors or donor siblings.

With longer embryo storage periods possible, it's likely that people will use these platforms to make contact with genetic relatives across many years, bypassing formal donor registries and regulated systems.

In this US case, the embryo donation took place within the same country. But that's not always the case. With the globalisation of fertility treatment, including international travel and the cross-border shipment of frozen sperm, eggs and embryos, it's increasingly common for people who are genetically related to live in different countries.

A 2024 Netflix documentary about sperm donation highlighted this issue, showing how a single donor fathered children in multiple countries, prompting calls for better regulation of international donor limits.

One of the most intriguing – and underexplored – questions is how people born from decades-old embryos will come to understand their origins.

While research on donor-conceived families suggests that they typically function well, the idea of being "frozen in time" for 30 years is unique. It introduces a temporal disconnect between conception and birth that may feel uncanny or dislocating.

Donor-conceived people are often curious about their genetic background – but being born from an embryo created before the internet or mobile phones adds another layer to this. It could influence how people make sense of their identity, family connections, and even their place in history, especially if their genetic siblings or donors are decades older, or deceased.

The long gap between fertilisation and birth raises profound questions not just about biology, but about belonging, narrative, and what it means to be from a particular time.

With rapid advances in reproductive technology, it's likely this won't be the last record-breaking case. As techniques improve and cultural boundaries around family and parenthood continue to evolve, we'll see more questions arise: about identity, genetics and what it really means to be part of a family.![]()

Nicky Hudson, Professor of Medical Sociology, De Montfort University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.