On 13 May 2025, a spinning top-shaped object plummeted through Earth's atmosphere from the dizzying heights of space, coming to rest on the russet sands of the Australian desert.

This was the W-3 capsule, the third of its kind launched by US space research company Varda Space Industries. For two months, it served as an experimental laboratory in low-Earth orbit, designed for the manufacture of new pharmaceuticals that can't be made on our planet.

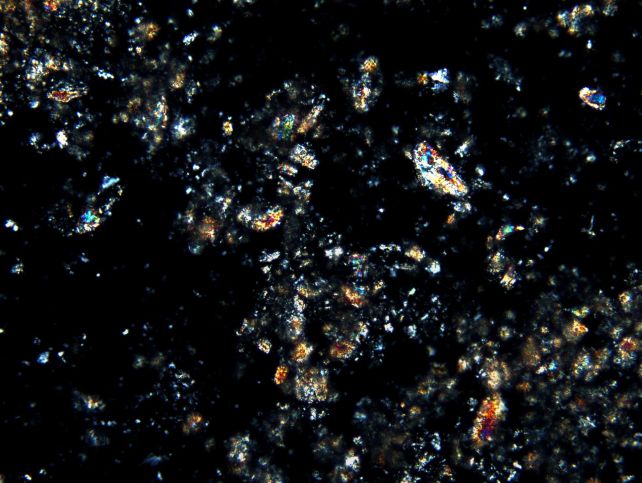

Varda claims to be the first private company to synthesize a pharmaceutical product in space and – crucially – to return it to Earth intact, demonstrating that crystallization processes that occur in microgravity are preserved even after returning to Earth's gravitational environment.

Related: Camera Inside Varda's Space Capsule Captured Its Wild Trip Back to Earth

"Crystal structures formed in microgravity have the potential to be different than those formed on Earth, despite both being the same active pharmaceutical ingredient," Varda's chief science officer, Adrian Radocea, told ScienceAlert.

"This difference in crystal structure can have various impacts on the molecule, whether that's improved formulations of existing drugs or securing a path to reach the pharmacokinetic profiles and routes of administration that enable the first approval of a drug under clinical development."

We take gravity for granted. After all, here on Earth, it's ubiquitous; the only way to escape it is through brief moments of free-fall. Almost everything humanity does takes place in one-g gravity, the downward gravitational acceleration at Earth's surface. If you drop an object, you instinctively know it's going to drop straight down.

This constant pull keeps us alive, but it also affects processes that take place within us. For small molecules, gravity affects the way they crystallize, causing them to clump together and grow unevenly. In addition, convection – a phenomenon that requires gravity – can stir the crystal as it forms, inducing further defects and instabilities.

Research efforts going back decades, conducted on parabolic flights and the International Space Station, have shown that a microgravity environment can stabilize crystallization, slowing it down and removing influences that lead to uneven growth.

"Because microgravity suppresses convective currents, buoyancy, and sedimentation, the resulting crystals are more uniform in size and structure. While gravity has little impact on chemical reactions, it plays a significant role in the hydrodynamics of crystallization and reactor-scale dynamics, which means that access to a microgravity environment can enable a fundamental change to the way we make medicines," Radocea explained.

"Achieving precise control over nucleation and growth impacts particle size distributions, polymorphic outcomes, particle morphology, and purity of crystals, which have wide-ranging applications across both small molecules and biologic drug substance development."

The idea of molecular manufacturing in space isn't necessarily a new one, but it seemed impossible to achieve at scale until relatively recently, with the development of reusable commercial rockets. Varda launched its first capsule, W-1, in June 2023; after months in orbit, it successfully reentered in February 2024.

It carried the ingredients for ritonavir, a well-studied HIV medication. When the capsule returned to Earth, it unexpectedly contained ritonavir Form III, a polymorph only recently identified on Earth in 2022.

And the surprises didn't stop there.

"Our recent hypergravity publication highlighted several unexpected results. The biggest to me was that even under agitation, gravity's effects influence particle size," Radocea said.

"The second biggest was how competition between sedimentation and concentration gradients could lead to a complex, non-monotonic trend with increasing gravity. It goes to show that running the tests and generating data is one of the best ways to learn."

The team plans to continue focusing on molecules that have known crystallization issues, finding new pathways to pharmaceuticals that can't be synthesized here on Earth. The W-4 capsule is up there right now, whizzing over our heads. W-5 and W-6 are scheduled for launch in early 2026.

Meanwhile, Varda has just announced a partnership with Australian launch services provider Southern Launch to land 20 capsules in the Koonibba Test Range in the desert of South Australia through 2028. The company's plans are ambitious, and it may not be long until lives are saved using drugs made in the strange frontier of space.

"We plan to have a drug in a human in the next ten years," Radocea said.

"The number of flights will increase over the next few years until there is a reentry every month or more. The challenge for us is to make that many capsules and fill them!"

If you're passionate about space, make sure to subscribe to our Spark newsletter and you could win an epic Space Coast adventure holiday in Florida.

To enter, readers simply need to subscribe to Spark, ScienceAlert's fact-checked weekly newsletter. Entries close at midnight 11 December 2025, and the winner will be randomly selected.

NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. Sweepstakes begins 10/10/2025; ends 12/11/2025. Void where prohibited.

For complete sweepstakes rules visit: sciencealert.com/space-competition-rules