Scientists have identified a single gene that gives rise to a rare form of diabetes, unique to newborn babies. Mutations of this gene can disable and ultimately kill off insulin-producing cells.

The new discovery reveals that the pancreas's beta cells – which create the insulin hormone our bodies need to manage blood glucose – are entirely dependent on the TMEM167A gene. This gene also affects neuron function.

"The ability to generate insulin-producing cells from stem cells has enabled us to study what is dysfunctional in the beta cells of patients with rare forms as well as other types of diabetes," says diabetologist Miriam Cnop, from Free University of Brussels in Belgium. "This is an extraordinary model for studying disease mechanisms and testing treatments."

Related: A Distinct New Form of Diabetes Is Officially Recognized

The international team mapped the genes of six babies who had been diagnosed with neonatal diabetes and microcephaly before 6 months of age. Five of these babies also had epilepsy.

This combination of diagnoses in infants is known as MEDS (microcephaly, epilepsy, and diabetes syndrome), and it's extremely rare, with only 11 individuals recorded so far.

Before this study, two genes had been linked to the syndrome: IER3IP1 and YIPF5. For a baby to be born with MEDS, they must have inherited two mutated copies of the gene, one from each parent.

Gene sequencing revealed that the same inheritance pattern applies to MEDS babies with the insulin-blocking variant of the TMEM167A gene, making this the third genetic cause of MEDS.

TMEM167A is active across the pancreas and the brain in both adults and infants, humans and mice, which may explain why these babies experience problems with the function of both organs.

To better understand how the TMEM167A gene variant causes diabetes, the researchers removed the gene from human pluripotent stem cells, replacing it with the variant taken from one MEDS patient's DNA. These stem cells were then encouraged to develop into beta cells.

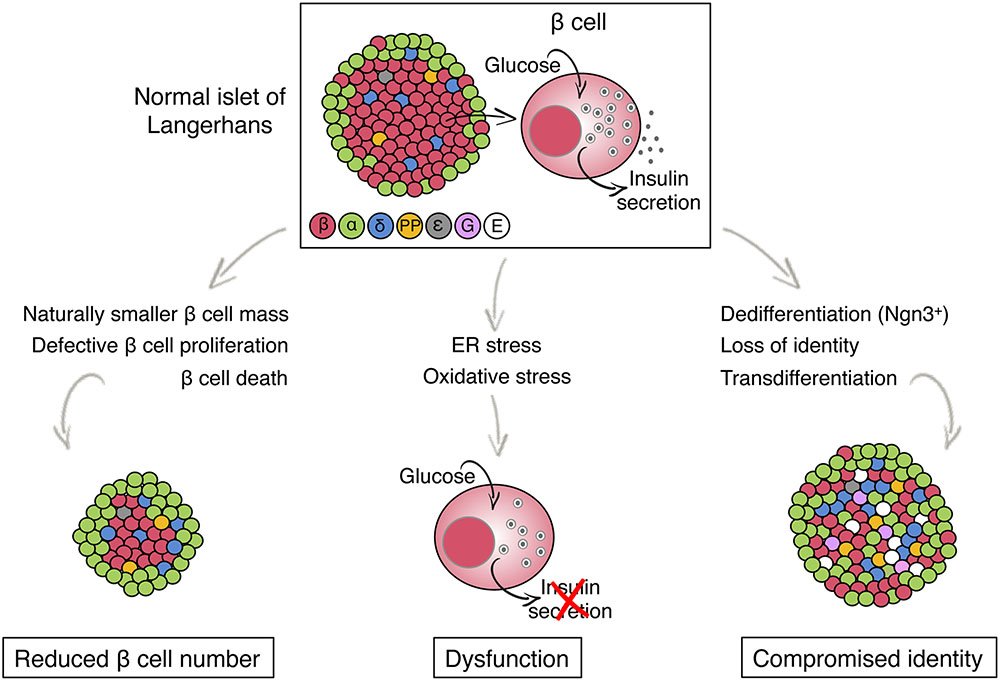

The gene variant didn't interfere with this development, but the beta cells produced were far from functional. Exposed to glucose, they did not release the insulin they're supposed to.

These cells also didn't cope well with the resulting disruptions to their endoplasmic reticulum (the maze-like structure inside a cell that shuttles material around): it tended to kill the beta cell.

"Finding the DNA changes that cause diabetes in babies gives us a unique way to find the genes that play key roles in making and secreting insulin," says University of Exeter molecular geneticist Elisa de Franco.

"The finding of specific DNA changes causing this rare type of diabetes in six children led us to clarifying the function of a little-known gene, TMEM167A, showing how it plays a key role in insulin secretion."

This research was published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.