When did you last find yourself with some spare time on your hands? A lack of free time, or 'temporal inequity', could be contributing to dementia risk, according to a new study.

In their new perspective article, researchers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia put forward the case for prioritizing time for our brain's sake.

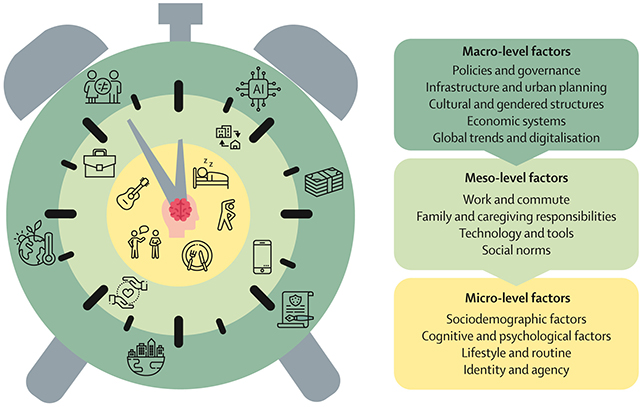

Available time is required to keep on top of our health in many ways: getting enough sleep, purchasing fresh food to eat healthily, and socializing regularly, for example, all compete with the daily demands of work, travel, and leisure.

Many of these lifestyle factors are also thought to be linked to our chances of developing dementia, including how lonely we feel, how much fast food we eat, the quality of the sleep we get, the level of exercise we get, and even our oral hygiene routines.

Related: Microplastics May Be Tied to Vascular Dementia Cases, Review Finds

"Up to 45 percent of dementia cases worldwide could be prevented if modifiable risk factors were eliminated," says epidemiologist Susanne Röhr. "However, many people simply don't have the discretionary time to exercise, rest properly, eat healthily, or stay socially connected."

"This lack of time – what we call 'time poverty' – is a hidden barrier to dementia risk reduction."

In other words, steps to reduce our risk of dementia are often compromised by the pressures of work, caring for children and parents, and everything else modern life throws at us means we don't always have time to make the best choices.

Some demographics have even less time than others, the researchers point out: it remains the case that women handle the majority of caregiving tasks around the world, while those on lower incomes typically have to work hours that are longer or less regular.

According to the researchers, we need to spend around 10 hours a day on brain care to stay healthy. That means getting enough sleep, eating and drinking well, interacting with other people socially, and exercising.

"For many, especially those in disadvantaged or caregiving roles, this simply isn't achievable under current conditions," says psychology researcher Simone Reppermund.

"Addressing time poverty is therefore essential if we are serious about preventing dementia."

Solutions would require a complex mix of community support, including improvements to childcare, more flexible working arrangements (such as four-day work weeks), improved public transport networks, and the right to disconnect.

It's a daunting challenge – but if steps aren't taken, the researchers argue, then dementia rates will continue to rise. And as is often the case with public health, it's the most disadvantaged who will bear the greatest burden.

"Brain health policy and research have focused heavily on individual behavior change," says neuropsychiatrist Perminder Sachdev.

"But unless people are given the temporal resources to act on these recommendations, we risk leaving behind those who need it most. Just as governments act on income inequality, we need to act on temporal inequity."

The research has been published in The Lancet Healthy Longevity.