A medieval Maya text for predicting solar eclipses has confused Western readers for centuries, but a pair of researchers may have finally cracked how it's really meant to work.

Indigenous civilizations in Mexico and Guatemala kept calendars for more than two millennia before Europeans invaded the Americas, helping them to predict the timing of important events in the heavens and on Earth with extraordinary accuracy.

Unfortunately, much of this knowledge – and the texts that contained it – was destroyed during the Spanish Inquisition, leaving only a few bits and pieces from which to reconstruct these advanced methods for celestial prediction.

Related: Scientists Think They've Finally Figured Out How a Maya Calendar Works

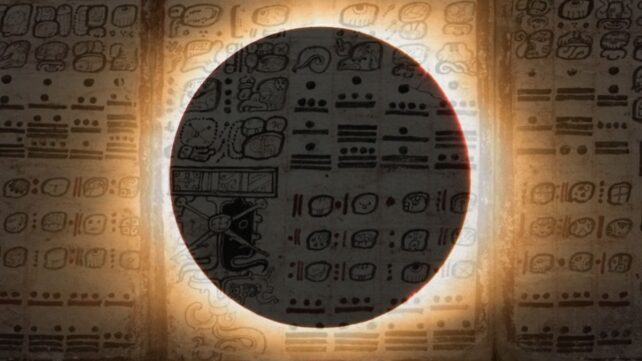

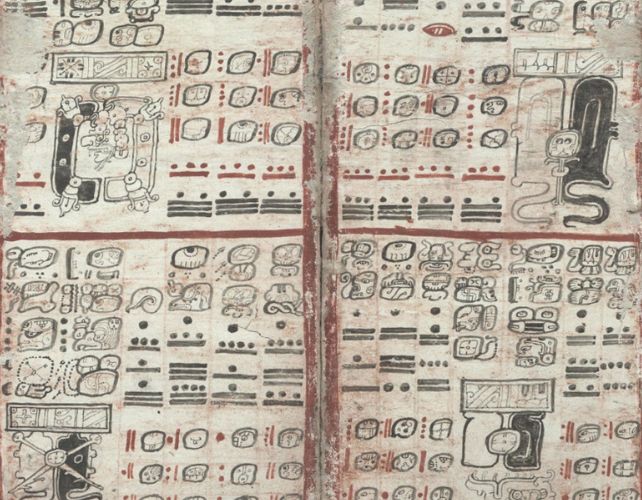

Dating to the 11th or 12th century, the Dresden Codex is one of only four hieroglyphic Maya codices to survive European colonization.

The bark paper codex is a 78-page accordion-style tome, with each page hand-written and illustrated in brilliant color, detailing astronomy, astrology, seasons, and medical knowledge.

Predicting solar eclipses – which occur when the light of the Sun is obscured by the Moon, casting a shadow upon Earth's surface – was serious business in Maya society, which was built and operated around celestial events.

"If you kept accounts of what happened at the time of certain celestial events, you could be forewarned and take proper precautions when cycles repeated themselves," explained University of Texas historian Kimberley Breuer in an article for The Conversation.

For instance, when the Sun was hidden behind the Moon, turning the day skies dark, members of Maya nobility would undertake bloodletting ceremonies to offer strength to the Sun god.

"Priests and rulers would know how to act, which rituals to perform and which sacrifices to make to the gods to guarantee that the cycles of destruction, rebirth and renewal continued," Breuer explained.

One table within the Dresden Codex allowed Maya calendar specialists, known as "daykeepers", to predict these eclipses for some 700 years. This table spans 405 lunar months (11,960 days), but how it actually worked has eluded scientists – until now.

Linguist John Justeson of the University of Albany in the US and archaeologist Justin Lowry of the State University of New York at Plattsburgh propose a convincing explanation for the calendar's proper use in a new article in Science Advances.

Juteson and Lowry reject the long-standing assumption that the table was reset at its final position (that is, that it was intended to be used on a continuous loop, returning to month 1 after reaching month 405).

The trouble is, using the table in this way doesn't actually work.

"Unanticipated eclipses could occur in the application of the next table or two if the final station of one table was used as the base for composing the next, and increasingly with each successive resetting," Juteson and Lowry write.

Instead, they propose that a new table is begun in the 358th month of the current table. With this approach, the table's predictions are only about 2 hours and 20 minutes early for both Sun and Moon alignment.

"This procedure would also entail that, occasionally, the first date in a successor table would be set at the 223rd month, about 10 hours and 10 min later relative to that alignment, to adjust for the gradually accumulating deviations of resettings at month 358," the authors write.

By comparing the table with our modern knowledge of eclipse cycles, they found that with this method, the Maya would have been able to accurately predict every solar eclipse observable in their territory between 350 and 1150 CE, since it corrects for the small errors that accumulate over time.

"Such revisions would maintain the viability of the table indefinitely, with departures of under 51 min over 134 years," the authors note.

It's a fascinating insight into the important role of a Maya daykeeper, and the advanced mathematics developed in the service of this lost civilization's spiritual connection to the cosmos.

This research was published in Science Advances.