The daily rhythm of genetic activity varies between individual cell types in ways that depend on their states of health, a recent study has found, revealing details on the relationship between Alzheimer's disease and our brain's operational routine.

This cycle, known as the circadian rhythm, tells us when to get out of bed and when to go to sleep, as well as keeping a host of internal biological processes running reliably on time across each 24-hour cycle.

Disrupted sleep patterns have been linked to Alzheimer's before, so researchers led by a team from the Washington University School of Medicine (WashU Medicine) took a closer look at the circadian rhythms of genes associated with the disease's risk factors.

Related: 'Young' Immune Cells Partly Reverse Alzheimer's Symptoms in Mice

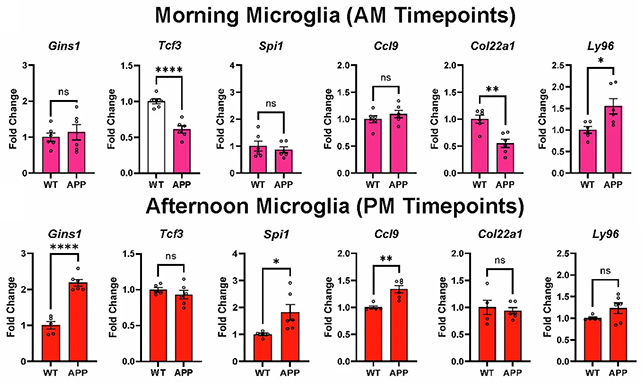

Comparing the brains of mice with an Alzheimer's-like condition with those of healthy mice at various ages, the researchers measured the expression of key genes within two specific cells: astrocytes, which assist neurons, and immune cells called microglia. The results were then confirmed in human tissue.

"There are 82 genes that have been associated with Alzheimer's disease risk, and we found that the circadian rhythm is controlling the activity of about half of those," says neurologist Erik Musiek, from WashU Medicine.

"Knowing that a lot of these Alzheimer's genes are being regulated by the circadian rhythm gives us the opportunity to find ways to identify therapeutic treatments to manipulate them and prevent the progression of the disease."

In other words, the ticking clocks that govern our cells' behaviors have a strong influence over a number of genes linked with Alzheimer's pathology in ways that could potentially interfere with the brain's normal function, and in particular, its ability to clear out toxic waste.

The Alzheimer's mice were genetically engineered to develop amyloid-beta protein plaques in the brain, which develop alongside the disease. It's not yet clear whether the clumps disrupt the rhythm or if a disrupted cycle triggers plaque formation, though the researchers suspect altered circadian clocks might be a cause for concern.

This makes sense in the context of what's already known about Alzheimer's, which is known to disrupt our body's everyday schedules. There's even a term for increased confusion that comes along in the late afternoon or early evening – known as sundowning.

"Circadian rhythms in gene expression are cell-dependent and context dependent, and provide important insights into glial function in health, Alzheimer's disease and aging," write the researchers in their published paper.

Around a fifth of the genes in the human genome are thought to change their expression in response to the body's clocks, influencing processes such as digestion, sleep, and body repair.

With evidence of daily oscillations in brain cells affected by neurodegeneration, researchers can investigate ways to counter the effects of pathology. Some sort of 'clock reset' on genes crucial to brain function might be a way of guarding against Alzheimer's.

"We have a lot of things we still need to understand, but where the rubber meets the road is trying to manipulate the clock in some way, make it stronger, make it weaker or turn it off in certain cell types," says Musiek.

"Ultimately, we hope to learn how to optimize the circadian system to prevent amyloid accumulation and other aspects of Alzheimer's disease."

The research has been published in Nature Neuroscience.