We really do 'fall' asleep, a new study shows. Far from gently drifting off, the brain rapidly transitions into sleep after passing a tipping point.

Using brain scans taken from thousands of volunteers, researchers from Imperial College London (ICL) and the University of Surrey in the UK discovered a surprisingly sudden change in electrical activity around 4.5 minutes before the onset of sleep.

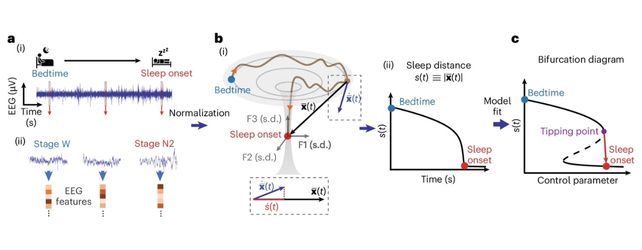

"We discovered that falling asleep is a bifurcation, not a gradual process, with a clear tipping point that can be predicted in real time," says ICL neuroscientist Nir Grossman.

Related: Humans Used to Sleep Twice Every Night. Here's Why It Vanished.

"The ability to track how individual brains fall asleep has profound implications for our understanding of the sleep process and for developing new treatments for people who struggle with falling asleep."

The team's model converted 47 features of brain activity captured by an electroencephalogram (EEG) into an abstract mathematical space. This allowed them to record changes in the brain between bedtime and sleep, which, when mapped as a trajectory, resembles a ball rolling down a steepening slope towards a fall.

Using this model, just a single night's recording of an individual person's brain activity was enough to predict the timing of sleep on later nights with 95 percent accuracy, and a tipping point error margin of 49 seconds, give or take.

"We can now take an individual, measure the brain activity, and in each second, say how far they are from falling asleep, every moment, with a precision that was not possible before," Grossman told journalist Grace Wade at New Scientist.

It's a fundamental new insight into something most of us take for granted. But beyond better understanding what healthy sleep looks like, this new knowledge could help specialists diagnose and treat sleep disorders like insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness, and even develop technology to warn drivers if they're getting drowsy.

It could also help with more precise monitoring of anaesthesia and serve as an indicator of brain health.

This research was published in Nature Neuroscience.