Denied of sleep, we find it but impossible to keep our eyes open and our thoughts focused. A new study based on fruit flies may have pin-pointed the origins of this biological lullaby, and with it a deeper understanding of our need for rest on a cellular level.

Researchers from the University of Oxford in the UK have identified our cell's mitochondria as responsible for signaling when the body has to get some shut-eye as soon as possible.

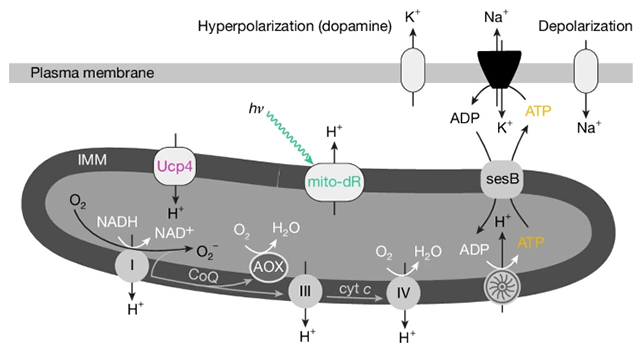

These tiny power generators cause a kind of metabolic overload in sleep-regulating neurons, the researchers suggest, which in simple terms indicates when our brain is running on empty. Through sleep, this overload can be reset, ensuring the brain remains in a healthy state.

Related: A Study Found Too Much Sleep Increases Risk of Death. Here's Why.

"We set out to understand what sleep is for, and why we feel the need to sleep at all," says physiologist Gero Miesenböck. "Despite decades of research, no one had identified a clear physical trigger."

"Our findings show that the answer may lie in the very process that fuels our bodies: aerobic metabolism."

The team studied neurons responsible for regulating sleep in fruit flies, which have enough biological similarities to humans to make them useful for research. Through a comparison of well-rested and sleep-deprived fruit flies, the researchers identified differences in gene activity and electrical signaling.

Overloaded mitochondria in sleep-deprived brains were found to shed electrons, increasing the generation of harmful waste products. The sleep-regulating neurons respond to these molecules by going into overdrive, making sleep a top biological priority.

"You don't want your mitochondria to leak too many electrons," says neuroscientist Raffaele Sarnataro. "When they do, they generate reactive molecules that damage cells."

Genetically engineering flies with a higher production of electrons in their sleep-regulating cells resulted in fruit flies that also slept more. Similarly, flies with a reduced level of electron generation slept less.

There are, of course, other pressures on sleep, from how many coffees you have per day to the alignment of your circadian rhythm – the internal schedule that tells your body when it's time for bed. But now we have an actual cellular mechanism controlling sleep, and showing why we can't do without it.

Anything new we learn about sleep can inform the treatment of sleep disorders and even neurological conditions such as Alzheimer's. These diseases are closely linked to sleep and the way it protects the brain, and connections to mitochondria could be something for future studies to investigate.

The study also joins some of the dots between metabolism, sleep, and lifespan. Smaller animals tend to sleep more and live shorter lives, and the activity of mitochondria – and the waste that needs clearing up – could be part of the reason why.

"This research answers one of biology's big mysteries," says Sarnataro. "Why do we need sleep? The answer appears to be written into the very way our cells convert oxygen into energy."

The research has been published in Nature.