Traces of a previously unknown group of people, genetically distinct from their neighbors, have persisted for at least 8,000 years in the central Southern Cone of South America, and Argentina in particular.

It's believed to be among the last places humans reached in our species' expansion across the world: Some of the earliest evidence of human presence in the continent's southernmost reaches dates to around 14,000 years ago, though this is greatly debated by archaeologists.

And yet, very few studies have looked at ancient human DNA from this region.

Related: Genes of a Lost South American People Point to an Unexpected History

A new study led by Harvard University human evolutionary biologist Javier Maravall López begins to fill in this blank spot on the map of our species.

"It's a major episode of the history of the continent that we just weren't aware of," says Maravall López.

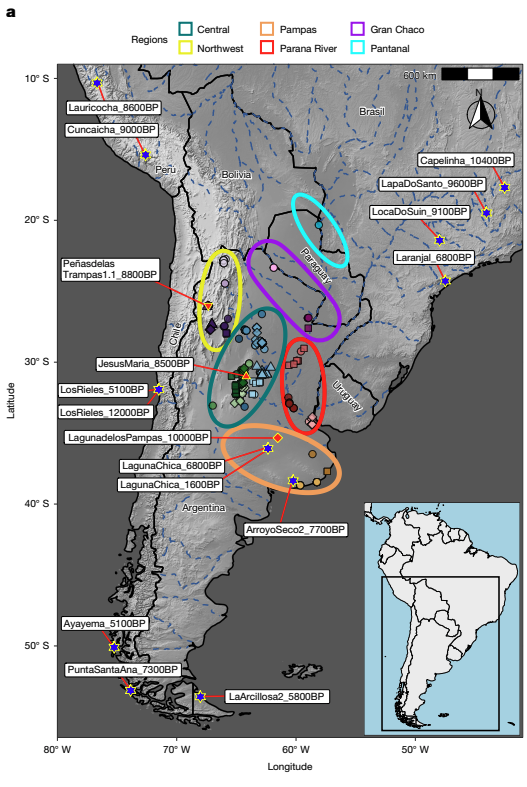

The team analyzed DNA from 238 ancient individuals from the central Southern Cone, whose lives collectively span 10 millennia.

The study increases the wealth of ancient DNA samples from this region by more than tenfold. It also places the data in the context of existing ancient DNA records dating back 12,000 years, from indigenous people who lived across the Americas before colonization.

In doing so, the researchers discovered a previously unknown lineage of humans. The earliest representative of this group lived around 8,500 years ago, and by about 4,600-150 years before present, most individuals in the DNA records were members of this group.

Although these central Argentinian people co-existed with two other distinct human genetic lineages during the Middle Holocene, the DNA shows surprisingly little evidence of inter-regional mingling.

DNA sampled from an individual found in the Pampas region, who lived around 10,000 years ago, showed that the inhabitants of this region had already started to develop genetic distinctions from other human groups in nearby parts of South America.

"We found this new lineage, a new group of people we didn't know about before, that has persisted as the main ancestry component for at least the last 8,000 years up to the present day," says Maravall López.

The authors were amazed that a region known for its vast diversity of languages and cultures could have such a consistent, homogenous ancestry, with such little migration.

"People with the same ancestry, in an archipelago-like fashion, were developing distinctive cultures and languages while being biologically isolated," says Maravall López.

The researchers expect this expanded set of ancient DNA will, in time, reveal further insights about ancient human history in Argentina.

"With large ancient DNA sample sizes, it is possible to learn details about the questions that really matter to many archaeologists – questions about how people are related to each other at a fine scale within archaeological sites as well as regionally," says Harvard geneticist David Reich, who was senior author on the paper.

"With ancient DNA data technology now, it is possible to build refined maps of population size change and migration, as now exist in rich detail in Europe, and as this study begins to do for Argentina.

"Such maps are transformative for our understanding of how people lived long ago, revealing demographic information about the past that was simply inaccessible before."

The research was published in Nature.