A specially devised hybrid treatment has shown tremendous potential for treating type 1 diabetes in mice, scoring full marks at preventing the condition in prediabetic animals and at reversing the condition in animals with fully developed diabetes.

What makes the new approach stand out is that it successfully combines immune system cells from both the patient mouse and a donor mouse, encouraging them to live in harmony without a need for immunosuppressive drugs for at least four months.

The researchers behind the work, led by a team from the Stanford School of Medicine, are hopeful the same approach could be successful in humans too. The treatment might also have potential for other procedures where transplants are required.

Related: Breakthrough Diabetes Treatment May Deliver Insulin Through a Skin Cream

"We believe this approach will be transformative for people with type 1 diabetes or other autoimmune diseases, as well as for those who need solid organ transplants," says developmental biologist Seung Kim, from the Stanford School of Medicine.

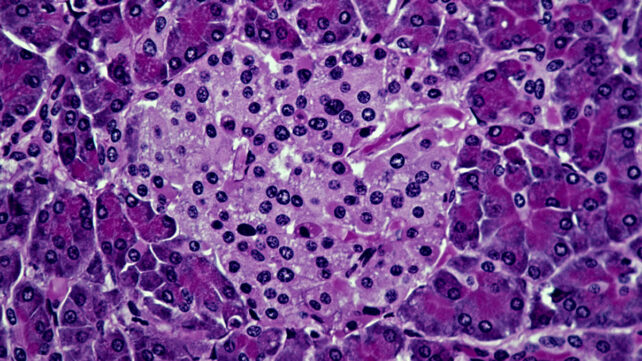

Type 1 diabetes is caused by the body's own immune system malfunctioning, triggering an attack on pancreatic cells called beta islets, which produce insulin. While healthy donor islets can be transplanted into the body, they also risk being attacked, if not completely rejected.

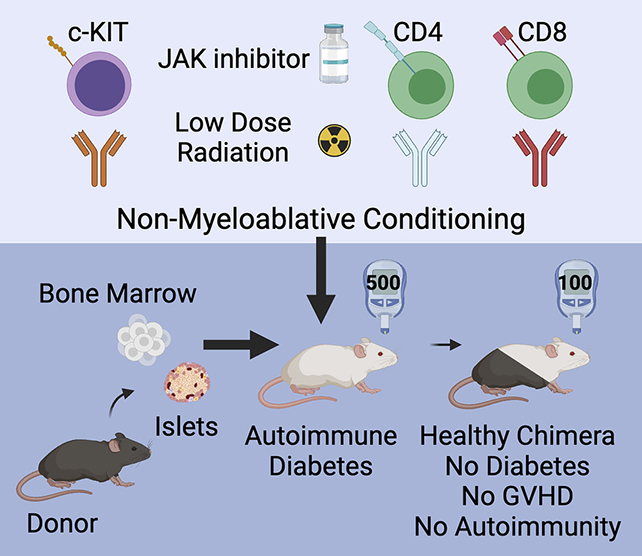

In this recent experiment, researchers subtly rebooted the mice's immune systems, preparing them before the transplant with an immune system inhibitor, a low dose of radiation, and a few select antibodies, as well as combining blood stem cells and islet cells from another animal.

As a result, the transplanted cells weren't attacked as foreign invaders, and the immune system began functioning normally again. While a small subset of islet cells showed some signs of inflammation, this critical tissue also wasn't attacked.

"We need to not only replace the islets that have been lost but also reset the recipient's immune system to prevent ongoing islet cell destruction," says Kim. "Creating a hybrid immune system accomplishes both goals."

The experiment represents a number of wins. The treated mice had their diabetes prevented or reversed, and none of them developed the graft-versus-host disease that often occurs in humans when cells are transplanted between people.

What's more, mixing donor and recipient immune cells has been shown to work for transplants before, including in previous studies by some of the same research team, which bodes well for human trials.

All of that said, plenty of challenges remain. For example, islet cells can only be donated after death, and must come from the same person as the blood stem cells. It's also unclear just how many of these cells would be needed for the procedure to be successful.

The researchers say they're currently looking at ways of getting more of the donated cells to survive, or figuring out ways of producing them in the lab from pluripotent human stem cells. We can't cure type 1 diabetes yet – but we're getting closer.

"The possibility of translating these findings into humans is very exciting," says Kim.

"The key steps in our study – which result in animals with a hybrid immune system containing cells from both the donor and the recipient – are already being used in the clinic for other conditions."

The research has been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.