A single-celled organism squirming about in the searing waters of California's Lassen Volcanic National Park has just set a record for heat tolerance.

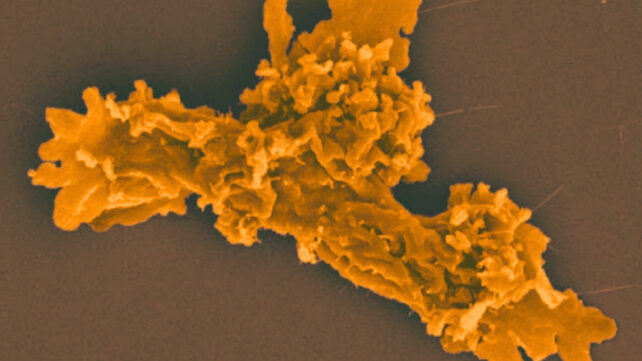

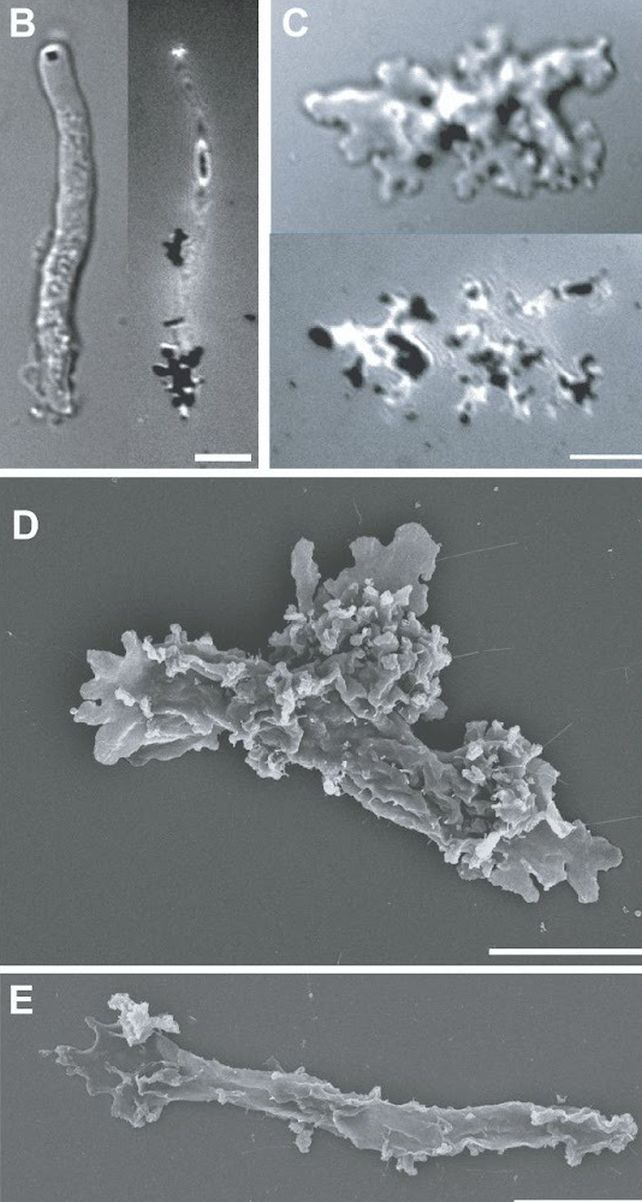

The newly named Incendiamoeba cascadensis – meaning "fire amoeba from the Cascades", as described in a preprint on bioRxiv – grows and divides at temperatures up to 63 degrees Celsius (145 Fahrenheit), the highest known temperature for a eukaryotic organism.

Moreover, it doesn't start growing until temperatures reach at least 42 degrees Celsius. This makes it an obligate thermophile – a creature that requires conditions far hotter than most eukaryotic organisms can endure.

Related: This Is The First Animal Ever Found That Doesn't Need Oxygen to Survive

"Our findings," writes a team led by biologists H. Beryl Rappaport and Angela Oliverio of Syracuse University in New York, "challenge the current paradigm of temperature constraints on eukaryotic cells and reshape our understanding of where and how eukaryotic life can persist."

Life on Earth tends to cluster around specific conditions, with the optimum temperature for most organisms, including humans, hovering around 20 degrees Celsius.

Some organisms, however, have adapted to conditions far harsher than the norm, from scorching volcanic vents under crushing ocean pressures, to acidic geothermal pools, to the driest desert on Earth.

The overwhelming majority of these extremophile organisms are prokaryotes, a group that includes bacteria and archaea. These are single-celled organisms, too, but they are dramatically different from eukaryotic organisms.

Prokaryotes are simpler, more primitive; they don't pack genetic material into nuclei or organelles such as mitochondria, but basically consist of just a cell membrane containing some rugged proteins and free-floating DNA, as well as a can-do approach to extreme environments.

The most heat-tolerant known organism on Earth is a carbon dioxide-munching archaeon called Methanopyrus kandleri that lives on undersea vents at temperatures up to 122 degrees Celsius, at a depth where ocean pressure keeps the water from boiling.

Eukaryotic life consists of all organisms, from amoeba to humans, that have nuclei, organelles, delicate internal membranes, and more complex genomes in their cells.

Eukaryotes are much more fragile than prokaryotes, with their cells and organelles easily rupturing or breaking down in hostile conditions. This makes the eukaryotic I. cascadensis all the more impressive.

The creature was found in steaming hot water collected from Lassen Volcanic National Park between 2023 and 2025. Rappaport, Oliveria, and their team recovered specimens of I. cascadensis from 14 of the 20 locations sampled.

The researchers then cultured the samples to understand how this heat-loving amoeba manages to survive.

So happy to announce our new preprint, "A geothermal amoeba sets a new upper temperature limit for eukaryotes." We cultured a novel amoeba from Lassen Volcanic NP (CA, USA) that divides at 63°C (145°F) 🔥 - a new record for euk growth! #protistsonsky 🧵

— H. B. Beryl Rappaport (@hbrappap.bsky.social) 2025-11-25T20:41:03.015Z

They separated the samples and grew them in different flasks, adding wheatberry to feed the bacterial communities inside so the bacterivorous amoeba would have something to eat.

They also changed the temperature of each flask to test the limits of I. cascadensis's endurance – trying out 17 different temperatures from 30 to 64 degrees Celsius, with four flasks at each temperature.

This is where things get truly mind-boggling.

Below 42 degrees Celsius, the amoeba didn't grow at all; the temperatures just weren't warm enough.

The best temperature range for growth was around 55 to 57 degrees Celsius, and mitosis – where a cell divides into two daughter cells – was directly observed at 58 and 63 degrees Celsius.

At 64 degrees Celsius, I. cascadensis was still moving around. It smashed the previous amoeba record of 57 degrees Celsius set by Echinamoeba thermarum, and even surpasses the long-assumed 60-degree upper limit for eukaryotic growth.

At 66 degrees Celsius, I. cascadensis started forming protective cysts, a strategy that allows amoebae to enter dormancy during challenging conditions.

It also formed cysts at 25 degrees Celsius. That's an unusually high lower limit, considering that most eukaryotes prefer temperatures well below that – and many thrive best at room temperature.

More experiments revealed that the amoeba stops moving at 70 degrees Celsius, but can revive if temperatures are brought back down.

Only when temperatures reached 80 degrees Celsius did I. cascadensis finally give up its tiny ghost.

An analysis of the genome provided clues about how the tiny organism can withstand such extreme conditions. It has adaptations for rapid signaling and heat-response pathways, as well as an expanded set of particularly heat-resistant proteins and heat-shock chaperones.

Finally, almost identical DNA sequences appeared in environmental DNA samples obtained in Yellowstone National Park and the Taupō Volcanic Zone in New Zealand.

Although DNA fragments don't make an organism, it suggests that I. cascadensis is not alone. Its discovery implies that life can be far more capable of adapting to extreme conditions than we thought, and one that may be useful for assessing the potential habitability of alien worlds.

"Incendiamoeba cascadensis proliferates at temperatures beyond what was thought possible for any eukaryotic organism. This discovery raises new questions about the true maximum temperature a eukaryotic cell can endure," the researchers write.

"These results have profound implications for our understanding of the evolutionary constraints on eukaryotic cells and the set of abiotic parameters that inform the search for life elsewhere in the Universe."

The team has posted their findings as a preprint on bioRxiv.