A critical nutrient used to produce the neurotransmitter serotonin may have turned up in samples collected from asteroid Bennu by NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission.

Tryptophan is one of the nine essential amino acids that the human body cannot make on its own, and, if confirmed, its detection in Bennu by researchers from NASA and the University of Arizona would mark the first time it has ever been found in an extraterrestrial sample.

It's a discovery that bolsters the theory that rocks from space delivered many of the ingredients for life to early Earth – and even suggests that we may have been underestimating their contribution.

"Our findings," writes a team led by geochemist Angel Mojarro of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, "expand the evidence that prebiotic organic molecules can form within primitive accreting planetary bodies and could have been delivered via impacts to the early Earth and other Solar System bodies, potentially contributing to the origins of life."

Related: Chemists Have Replicated a Critical Moment in The Creation of Life

The idea that the chemistry for life was at least partially delivered to a nascent Earth by comets and asteroids is one of the leading theories on how we came to be. The influx of evidence across a range of sources, from deep-space observations to the retrieval and analysis of asteroid samples, has only strengthened this cosmic explanation.

Samples from asteroids Ryugu and Bennu have yielded some truly fascinating ingredients, including extensive inventories of amino acids (which are the building blocks of proteins) and nucleobases (the basic units that make up RNA and DNA).

Only one nucleobase has been found on Ryugu, but all five common nucleobases appeared in Bennu samples.

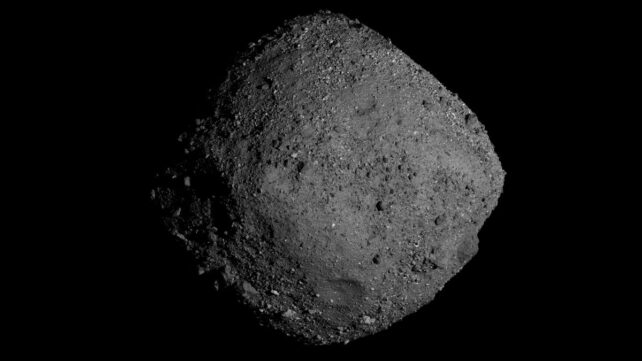

Now, Mojarro and his colleagues have performed a new analysis of material from Bennu – a space rock as old as the Solar System – focusing on amino acids and nucleobases to gain a greater understanding of extraterrestrial prebiotic chemistry and its origins.

In particular, they wanted to clarify the chemical reaction pathways by which the amino acids may have formed, billions of years ago.

The team examined powdered fragments of the asteroid, testing for the 20 amino acids that build protein in the body (nine of which the body can't make, and must obtain from food), as well as the five common nucleobases that encode our genetic instructions (adenine, guanine, cytosine, thymine, and uracil).

Their analysis confirmed the presence of the 14 amino acids detected in a previous study, as well as the nucleobases. They also found several non-biological amino acids and nucleobases, confirming the extraterrestrial origin of the molecules in the samples.

To their surprise, the researchers also detected a signal for tryptophan – faint, but present across multiple portions of a Bennu sample.

Your brain uses tryptophan to make serotonin, the neurotransmitter that helps, among other functions, to regulate your mood, and feelings of wellbeing and happiness.

People with low serotonin are prone to depression and anxiety. Your brain also uses tryptophan to make melatonin, and your body can use it to make vitamin B3. We can only acquire it from foods such as poultry, fish, dairy, nuts, and eggs.

The amino acid is relatively fragile, making it unlikely to survive inside a meteorite falling to Earth in a blaze of atmospheric entry. This might explain why it hasn't been found in any meteorite samples to date.

However, an asteroid sample retrieved from space and carefully ferried to Earth in a protective canister doesn't undergo the same rigors. The detection, therefore, suggests that there may be prebiotic ingredients hanging about on asteroids that remain undetected in an extraterrestrial context, simply because they're typically too fragile to survive a trip to Earth without help.

This also means that fragile amino acids such as tryptophan can form in a non-biological context, so their mere presence alone cannot be interpreted as a definitive sign of life.

Finally, the researchers carefully examined different mineral compositions in the samples, since Bennu doesn't have a homogeneous composition but is brecciated, like a rich, densely packed fruitcake. They found that different processes, many of which involved water, took place to produce the molecules.

That suggests that no single process can produce the range of prebiotic chemistry observed in the dust of Bennu.

It also gives us a little more insight into how the ingredients for life can come together out of the dusty debris circling a baby star, and points to some promising lines of enquiry for future astrobiology research.

"Additional targeted analyses of tryptophan using other techniques capable of measuring its enantiomeric and isotopic compositions are needed to firmly establish its origin in Bennu and possibly other astromaterials," the researchers write.

"Sample return missions from a variety of planetary bodies are accordingly crucial to enabling new discoveries and elucidating products of cosmochemistry."

The findings have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.