An expanse of ancient rock in the high-altitude Torotoro National Park in Bolivia has been revealed as the largest dinosaur tracksite ever recorded.

There, on the eastern flank of the Andes, paleontologists have cataloged the famous Carreras Pampa tracksite, counting almost 18,000 individual dinosaur tracks, made by running, sauntering and even swimming beasts around 70 million years ago – the last age of the dinosaurs before the mass extinction that spelled their demise.

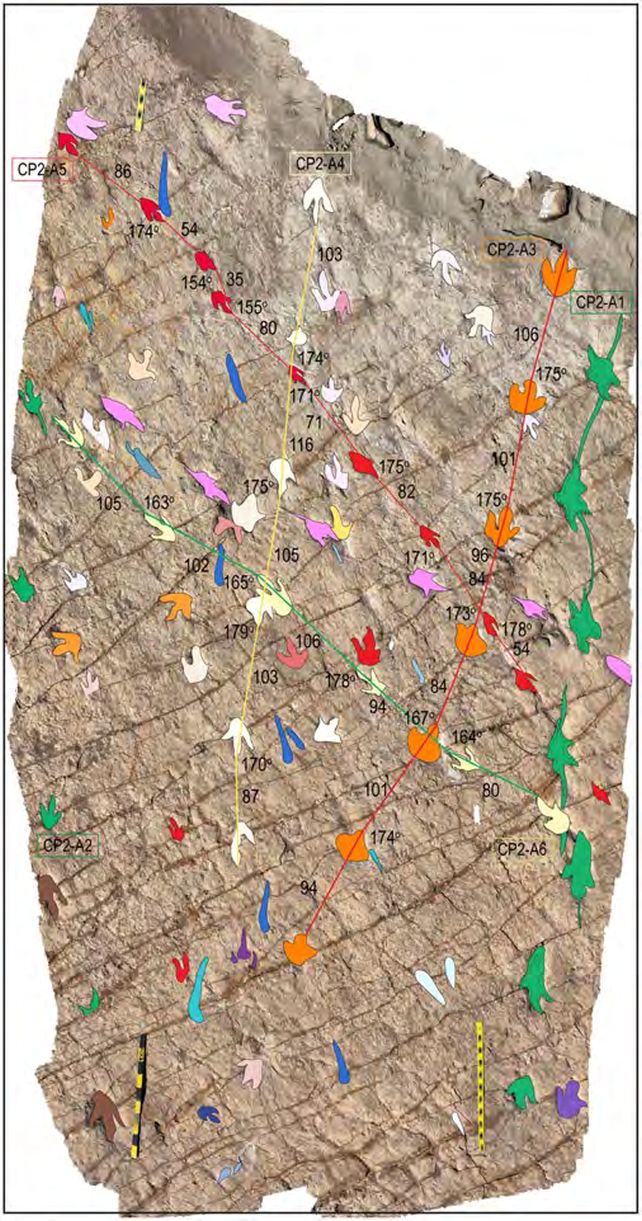

The site includes a record-smashing 16,600 three-toed tracks across 1,321 trackways and 289 lone prints, as well as 1,378 swim tracks across 280 trackways. They all belong to theropods, a group that includes all known carnivorous dinosaurs as well as modern birds.

It's an absolutely astonishing site, made even more remarkable by the unique set of environmental conditions that contributed to its preservation.

Related: Giant Set of Dinosaur Tracks in Alaska Is So Big It's Called 'The Coliseum'

"The Carreras Pampa tracksite in Torotoro National Park, Bolivia, is an extraordinary assemblage of dinosaur and avian ichnites [fossil tracks], theropod swim tracks, tail traces, and various invertebrate burrows," writes a joint US-Bolivian team led by paleontologist Raúl Esperante of the Geoscience Research Institute in the US.

Every second of every day, terrestrial creatures are leaving their marks on the surface of our world. The vast majority of those marks will vanish quite quickly – but in a few rare instances, circumstances will align in exactly the right way to preserve otherwise fleeting impressions of a creature's passage.

The Carreras Pampa tracksite was once the shoreline of an ancient, shallow freshwater lake – long since evaporated, but an environment uniquely suited to the preservation of tracks in the soft, waterlogged, carbonate-rich mud. The sheer preponderance of tracks suggests that this lake was a valuable resource for the animals living nearby.

The layer in which the tracks were preserved, the researchers explained, had a list of exceptional properties that enhanced its preservation capabilities. It consisted primarily of oval calcium carbonate grains – nested ostracod shells and ooids – with the remaining 35 percent made up of fine-grained silicates.

This created a surface that, when wet but not submerged, was soft enough to make a deep indent when stepped onto, but firm enough to retain that indent long enough for fossilization processes to set in, after a sediment layer covered it.

In addition, the tracks were not obscured by later tracks over the top. It's a perfect storm of conditions that produces a site where multiple track types remained frozen for eons.

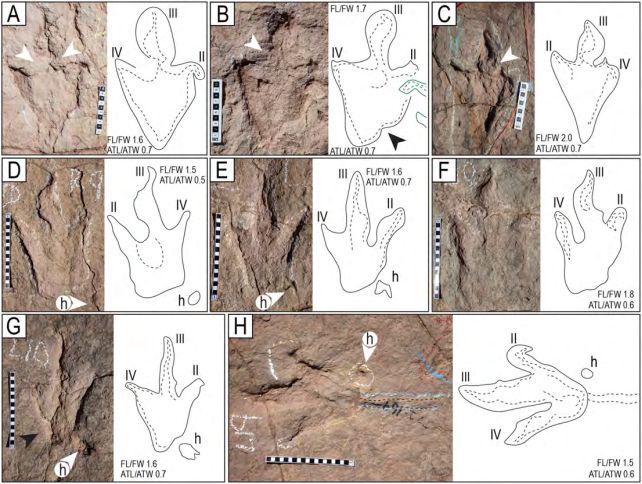

There are the usual footprints that the term 'dinosaur tracks' evokes, of course. But the site also preserved claw marks and indentations, tail marks, and the scratches from feet just scraping the lakebed as a dinosaur swam over.

The footprints range in size from more than 30 centimeters (1 foot) in length to tiny, less than 10 centimeters. They're also aligned in two main directions, suggesting that the dinosaurs were walking back and forth along the lakeshore.

Most of the footprints are from theropod feet sized between 16 and 29 centimeters – small- to medium-sized dinosaurs that would have stood about as tall as an adult human, at most.

The researchers identified 11 different types of tracks. They were even able, in some cases, to identify sharp turns as the dinos ran along the water.

"Theropod footprints with tail-drag traces are abundant and well-preserved in the tracksite, appearing in trackways featuring shallow, deep, and very deep tracks," they write.

"The tail traces suggest that dinosaurs exhibited some form of locomotive behavior in response to sinking into soft substrate, which resulted in their tails coming into contact with the surface."

Carreras Pampa, the researchers say, is now one of the world's important dinosaur tracksites, with the highest recorded number of theropod tracks, the highest recorded number of swim tracks, and a record of preservation types that reveals how the dinosaurs were behaving – a rare insight into a once-thriving ecosystem.

This, they say, suggests it should be classified among the most exceptional dinosaur sites, known as Lagerstätten.

"The abundance and exceptional preservation of these tracks and traces make the Carreras Pampa tracksite an ichnologic concentration and conservation Lagerstätte," they write.

"The quality of preservation, the exceptionally high number of tracks, and the diversity of behaviors recorded make the Carreras Pampa tracksite one of the premier dinosaur track sites in the world."

The research has been published in PLOS One.