A calorie-restricted diet could slow down the aging that naturally happens in the brain as we get older, according to a new study of rhesus monkeys, and the findings could also be relevant to brain diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Researchers led by a team from Boston University analyzed the brains of 24 rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that had been fed calorie-restricted or standard diets for more than 20 years.

After these lifelong dietary differences, the researchers found signs of healthier nerve communication and protection in brain tissue samples from the animals that consumed 30 percent fewer calories.

It adds to what we already know about diets with limited calories: By giving the body less fuel to work with, these diets can put the body's metabolism into a more efficient mode – which, in this study, appears to have protected against some of the cellular wear and tear that normally comes with aging.

Related: Weight Gain Might Be Linked to 'Lifestyle Instability', Not Just Calories

"While calorie restriction is a well-established intervention that can slow biological aging and may reduce age-related metabolic alterations in shorter-lived experimental models," explains first author, Boston University neurobiologist Ana Vitantonio, "this study provides rare, long-term evidence that calorie restriction may also protect against brain aging in more complex species."

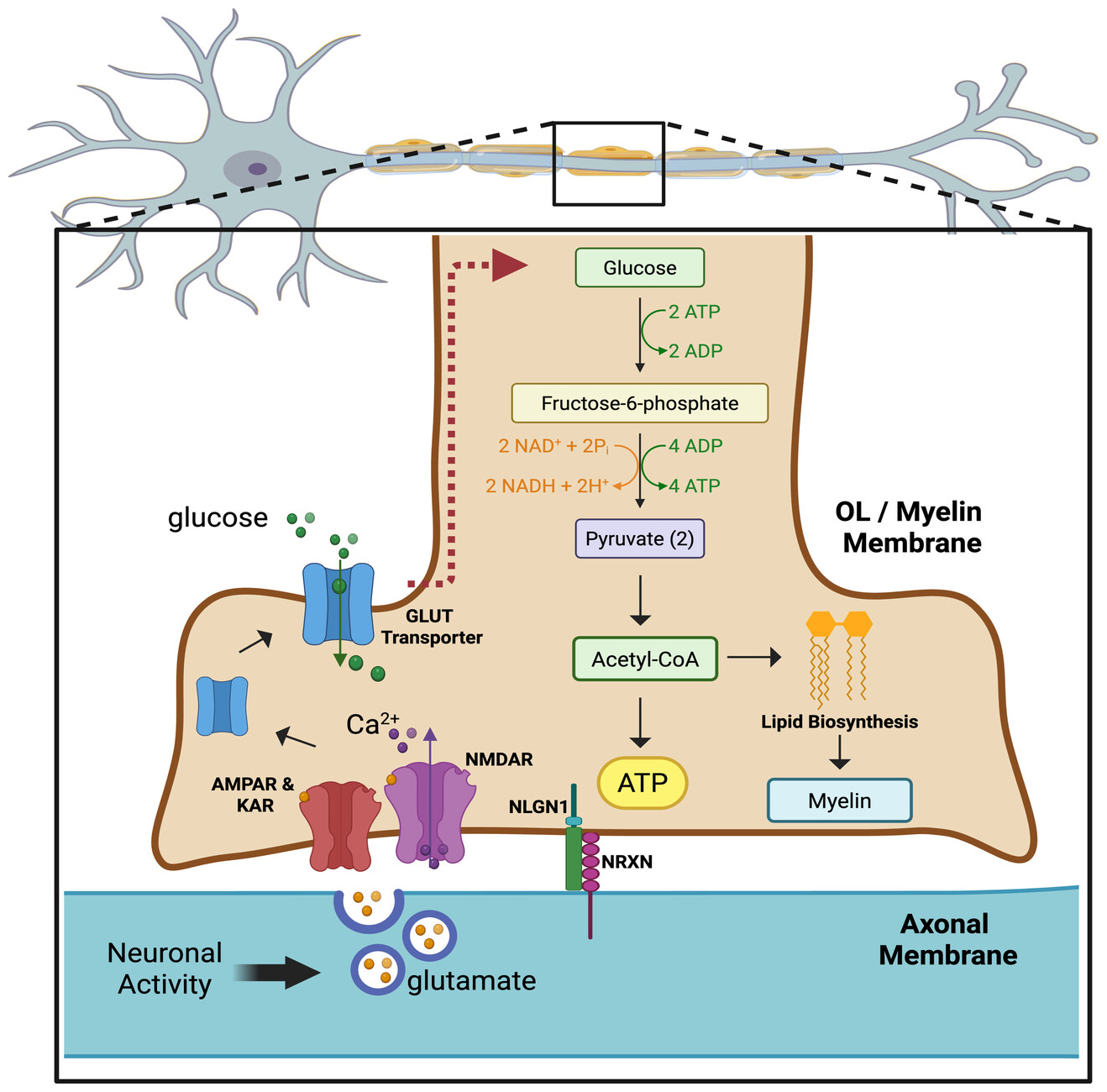

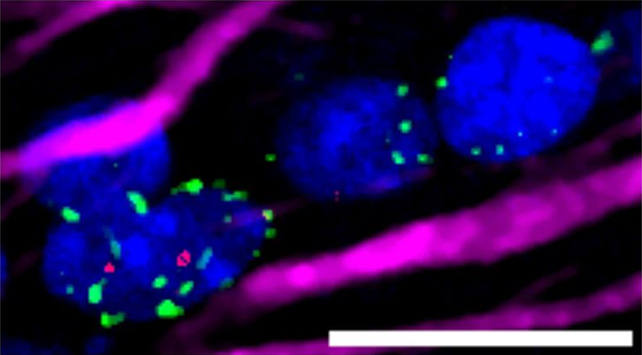

The team focused specifically on myelin, the fatty coating around nerve fibers in the brain that protects them and speeds up communication between them. As the brain gets older, myelin degrades, which can trigger inflammation.

In the monkeys fed calorie-restricted diets, there were strong signs that the myelin wrapping around nerves in the brain was in a better state: Myelin-related genes were more active, and key metabolic pathways related to myelin production and maintenance were functioning better.

The cells that produce myelin and help keep it healthy were working more efficiently, too, the researchers found – stopping some of the signs of aging seen in the monkeys on standard diets.

"This is important because these cellular alterations could have implications that are relevant to cognition and learning," says neurobiologist Tara Moore, from Boston University.

As with the rest of our bodies, the brain's machinery tends to break down as the years roll by. In some cases, mechanisms designed to maintain good brain health actually go haywire and become harmful, leading to neuroinflammation.

That's why conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease become much more likely in old age – because brain cells are in a worse state, and their overactivity might cause some inadvertent damage, especially if the protective sheath around nerve cells is deteriorating with age, too.

In recent years, scientists have been revisiting the link between Alzheimer's disease and myelin decline, adding experimental evidence of myelin breakdown to imaging data from people with rapid cognitive decline. This study adds another clue and a way to possibly intervene – through diet.

While this research was only carried out in a relatively low number of monkeys, their brains share plenty of similarities with humans, so there's good reason to think the findings might apply to people, too – something which future studies could look at.

"Dietary habits may influence brain health, and eating fewer calories may slow some aspects of brain aging when implemented long term," says Moore.

Though as we're learning from other studies, there are many factors beyond diet that can influence brain aging, including sleep quality and language learning.

The research has been published in Aging Cell.