Experiments on an ultra-rare genetic mutation that causes neurodegeneration in children have helped uncover a new mechanism by which brain cells die.

The findings raise the possibility that similar cell-death pathways contribute to other brain diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, or Huntington's.

A team led by scientists at the German research center, Helmholtz Munich, found that mutations within this one gene caused neurons in mice to experience progressive inflammation and cell death. In lab-grown human brain cells derived from patient skin cells with the same mutation, neurons died in a strikingly similar way.

Related: The Sad Case of The Youngest-Ever Alzheimer's Diagnosis

This specialized form of programmed cell death, called ferroptosis, is triggered by iron accumulation and oxidative damage to the cell membrane.

The mechanism is reminiscent of cell death in dementia, the researchers argue, based on their analysis of proteins expressed by neurons. Recent evidence, for instance, suggests that ferroptosis is linked to Alzheimer's.

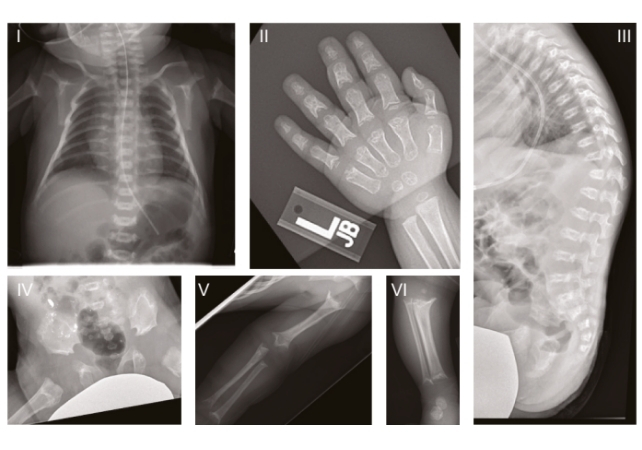

In humans, this specific ultra-rare genetic disorder is called Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SSMD), which is characterized by severe brain and skeletal abnormalities. It was first described in 1980, and since then, only a few dozen cases have been officially recorded, many describing children dying in early infancy.

In recent years, genome-wide sequencing has linked SSMD to mutations in the gene encoding an enzyme called GPX4, often considered to be a 'guardian' of ferroptosis for the way it protects cell membranes from oxidative damage.

While mutations in this gene do not necessarily cause early-onset dementia, this new research in mice cells and lab-grown ' organoid' mini-brains reveals how GPX4 may protect neurons and how its dysfunction may lead to cell death.

The study focused on three children with SSMD in the US who showed varying degrees of brain atrophy and who had mutations in the same functional region of the GPX4 gene. These results were then used for further study in mice and in lab-grown brain cells, created from the skin cells of an SSMD patient.

Marcus Conrad, a cell biologist and director of the Institute of Metabolism and Cell Death at Helmholtz Munich, likens the GPX4 enzyme to a surfboard.

"With its fin immersed into the cell membrane, it rides along the inner surface and swiftly detoxifies lipid peroxides as it goes," he explains.

But when this specific GPX4 mutation is present, the fin of the board is missing. This means the enzyme isn't anchored to the membrane, and it can't work to protect the neuron.

Lab-grown neurons derived from the stem cells of SSMD patients were especially vulnerable to ferroptosis. Blocking ferroptosis in mice and lab-grown cells with a chemical compound seemed to slow the neural death.

"Our data indicate that ferroptosis can be a driving force behind neuronal death – not just a side effect," says Svenja Lorenz, a cell biologist at Helmholtz Munich.

"Until now, dementia research has often focused on protein deposits in the brain, so-called amyloid ß plaques. We are now putting more emphasis on the damage to cell membranes that sets this degeneration in motion in the first place."

Dementia is often considered to be an elderly person's disease, but in some tragic scenarios, cognitive decline related to memory issues can begin much earlier in life. Childhood dementia is a rare brain condition that leads to memory loss and confusion, and genome studies have linked it to more than 100 rare disorders that children are born with.

Investigating tragic cases like these gives scientists crucial insights into how neurodegeneration can occur, and what can be done about it.

"It has taken us almost 14 years to link a yet-unrecognized small structural element of a single enzyme to a severe human disease," says Conrad.

"Projects like this vividly demonstrate why we need long-term funding for basic research and international multidisciplinary teams if we are to truly understand complex diseases such as dementia and other neurodegenerative disease conditions."

The study was published in Cell.