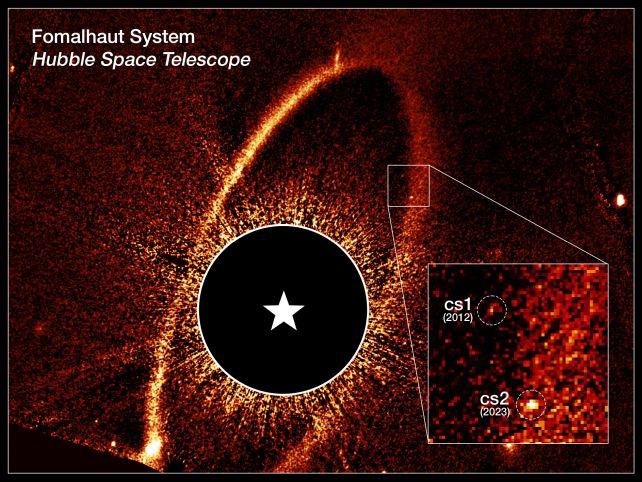

For only the second time ever, a collision between two asteroids has been observed around an alien star not too far beyond the Solar System's borders.

That star is Fomalhaut, a mere cosmic baby at just 440 million years old, still surrounded by a disk of debris leftover from its formation. At just 25 light-years away, Fomalhaut constitutes an excellent laboratory for studying the disk processes that are the precursors to planet formation.

And now, the Hubble Space Telescope has revealed an event that may be one of those processes: two chunks of rock, each estimated to be around 60 kilometers (37 miles) across. Had they not smashed each other to dust, these tiny seeds could have gone on to grow into planets orbiting the star.

Related: Something Is Warping The Disk Around One of The Brightest Stars in Our Sky

"This is certainly the first time I've ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system," says astronomer Paul Kalas of the University of California, Berkeley.

"It's absent in all of our previous Hubble images, which means that we just witnessed a violent collision between two massive objects and a huge debris cloud, unlike anything in our own Solar System today. Amazing!"

This is not Fomalhaut's first rodeo. Back in 2004, astronomers spotted a planet-bright object in its orbit. Follow-up observations involving direct images taken in 2012 seemed to confirm it. The putative gas giant, Formalhaut b, was even given a name – Dagon.

But by the time new observations were taken in 2014, however, Dagon had completely vanished. Astronomers concluded that the best explanation for the disappearing object was that it was never a planet at all, but a bright, expanding dust cloud from a violent collision between two asteroids.

Fast forward to 2023, when Hubble turned its gaze back to Fomalhaut to see if the wacky star had been up to more shenanigans. Spoiler alert: Shenanigans were in full swing. A blob of light had appeared in the star's vicinity, looking suspiciously similar to Dagon.

"With these observations, our original intention was to monitor Fomalhaut b, which we initially thought was a planet," says astronomer Jason Wang of Northwestern University.

"We assumed the bright light was Fomalhaut b because that's the known source in the system. But, upon carefully comparing our new images to past images, we realized it could not be the same source. That was both exciting and caused us to scratch our heads."

Kalas and his colleagues have named the blob Fomalhaut cs2, for "circumstellar source 2"; Dagon, meanwhile, has been downgraded to Fomalhaut cs1. RIP Dagon.

"Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight," Kalas explains. "What we learned from studying cs1 is that a large dust cloud can masquerade as a planet for many years. This is a cautionary note for future missions that aim to detect extrasolar planets in reflected light."

Based on the Hubble observations, as well as previous observations of the changes exhibited by cs1, the researchers calculated that both clouds were likely the result of collisions between small, similarly sized bodies. Both, interestingly, also occurred at a similar location on the outskirts of the Fomalhaut disk.

"Previous theory suggested that there should be one collision every 100,000 years, or longer. Here, in 20 years, we've seen two," Kalas says.

"If you had a movie of the last 3,000 years, and it was sped up so that every year was a fraction of a second, imagine how many flashes you'd see over that time. Fomalhaut's planetary system would be sparkling with these collisions."

One collision – a single datapoint in isolation – tells you that this is a thing that can happen in the particular set of circumstances in which it took place. A second collision opens up a whole new world. A second collision gives you statistics.

"The exciting aspect of this observation is that it allows researchers to estimate both the size of the colliding bodies and how many of them there are in the disk, information which is almost impossible to get by any other means," says astronomer Mark Wyatt of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

"Our estimates put the planetesimals that were destroyed to create cs1 and cs2 at just 37 miles or 60 kilometers across, and we infer that there are 300 million such objects orbiting in the Fomalhaut system."

The star's immediate environment is certainly interesting. Other recent observations have shown that the disk has concentric gaps – a sign that something is clearing the debris, perhaps a forming planet sweeping up the path of its orbit. However, the planets themselves are yet to be seen.

Meanwhile, 2023 JWST observations showed a large knot of dust in the same outer ring in which cs1 and cs2 appeared. Astronomers at the time attributed it to yet another collision, although that interpretation is yet to be confirmed.

Although Fomalhaut raises a lot of questions to which we are yet to find answers, the emerging picture suggests a dynamic environment that could be indicative of early planet formation.

"The system is a natural laboratory to probe how planetesimals behave when undergoing collisions, which in turn tells us about what they are made of and how they formed," Wyatt says.

The researchers will continue to use both Hubble and JWST to observe cs2 to see how it evolves in the years ahead.

"We will be tracing cs2 for any changes in its shape, brightness, and orbit over time," Kalas says. "It's possible that cs2 will start becoming more oval or cometary in shape as the dust grains are pushed outward by the pressure of starlight."

The research has been published in Science.