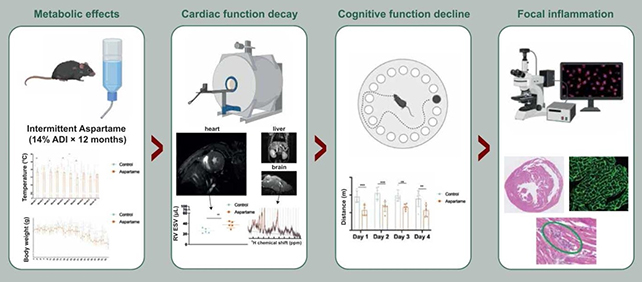

The artificial sweetener aspartame can be found in everything from chewing gum to fizzy drinks and tabletop sweeteners. A new study of mice suggests that even at low doses, the sugar substitute may have negative impacts on heart and brain health over the long term.

Over the course of a year, researchers led by a team from the Center for Cooperative Research in Biomaterials in Spain added small amounts of aspartame to the diets of male mice. This dose, given for several days each fortnight, was equivalent to about one-sixth of the currently acceptable daily human intake set by the World Health Organization.

These mice lost more weight than untreated controls, having 10-20 percent less body fat, on average, by the end of the study. But they developed worrying signs of heart and brain decline that warrant further investigation to see if the same effects might happen in humans.

Related: Common Sweetener Could Damage Critical Brain Barrier, Risking Stroke

"The study demonstrates that long-term exposure to artificial sweeteners can have a detrimental impact on organ function even at low doses, which suggests that current consumption guidelines should be critically re-examined," the researchers write in their published paper.

The researchers noticed the hearts of mice given aspartame had reduced pumping efficiency, along with minor structural and functional changes. This indicates impaired performance and increased cardiac stress, the researchers suggest.

The uptake of glucose, an essential fuel, into the brain also changed in aspartame-treated mice: It initially spiked, but then dropped significantly by the end of the year-long experiment. That could potentially sap the brain of the energy it needs to function properly.

This was reflected in the aspartame-treated mice struggling more with memory and learning tasks, hinting at cognitive decline. The animals that had consumed aspartame moved slower and took longer to escape from mazes, for example.

"It is concerning," the researchers write, "that the mild regime applied here, which is well below the equivalent maximum permitted for humans, administered only three days per two weeks, can alter heart and brain function, and heart structure."

It's important to put all of this into the context of other studies. The researchers note that the cognitive changes were "relatively mild" compared to earlier studies of mice that consumed aspartame daily, or for a shorter period.

"Either the aspartame-free intervals attenuated the magnitude of the behavioral changes, or mature mice are more tolerant of aspartame than younger animals, or else the mice adapt to long-term aspartame exposure," write the researchers.

"Until the neurological sequelae of aspartame are better understood, children and adolescents should probably avoid aspartame as far as possible, especially as a regular component of the diet."

There are a lot of variables here – dosage levels, study duration, and associated diet – even before we consider that these findings are from mice rather than people (and only male mice at that).

Nevertheless, the study adds to mounting evidence that artificial sweeteners aren't necessarily healthy substitutes.

We've already seen artificial sweeteners linked to biological changes associated with dementia, fatty arteries, and liver cancer – though as yet there's no clear proof of direct cause and effect.

While aspartame and similar products can reduce the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes by providing sweetness without any calories, questions remain about what level of consumption is safe.

"These findings suggest aspartame at permitted doses can compromise the function of major organs, and so it would be advisable to reassess the safety limits for humans," the researchers conclude.

The research has been published in Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy.