Roman soldiers garrisoned at the fort of Vindolanda, located near Hadrian's Wall in northern England, were riddled with parasites that sapped their fighting fitness.

In addition to lice-infested tunics and runny noses, Rome's military might have dealt with chronic gut infections that caused diarrhea, stomach cramps, and nausea, according to a jointly performed archaeological study by researchers from Cambridge and Oxford.

"While the Romans were aware of intestinal worms, there was little their doctors could do to clear infection by these parasites or help those experiencing diarrhea, meaning symptoms could persist and worsen," says Marissa Ledger, an archaeologist at McMaster University in Canada who co-led the study while completing her PhD at Cambridge.

"These chronic infections likely weakened soldiers, reducing fitness for duty. Helminths alone can cause nausea, cramping, and diarrhea."

Related: Study Reveals British History's Most Worm-Infested People, And It's Not Who You Think

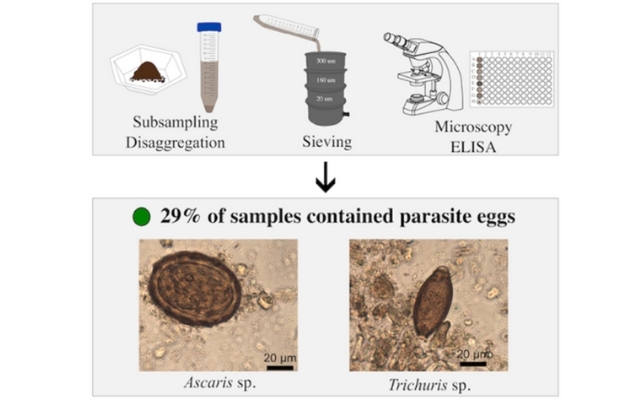

The researchers analyzed just under 60 samples of sewer drain sediments containing ancient poop and other detritus that washed away from the fort and nearby settlements, dating to the 3rd century CE. The glut of grossness originated from the fort's latrine drain, which carried waste to a stream north of the site.

Previous archaeological explorations in the area have unearthed a trove of organic materials that have been preserved in Vindolanda's waterlogged soil. These finds include more than 5,000 leather shoes, a wooden phallus, and over 1,700 thin wooden tablets inscribed with ink, which document day-to-day habits at the fort.

This daily martial life would have revolved around guarding Hadrian's Wall, just north of the fort. Established in the early 2nd century CE, the wall is a defensive fortification running east-to-west from the North Sea to the Irish Sea.

To ease occupation on this Roman-British frontier, the fort had baths, toilets, and drinking water. Regardless, the soldiers still suffered from intestinal infections, including roundworms, whipworms, and potentially Giardia, a diarrhea-causing microscopic single-celled animal.

This latter pathogen is an exciting find for researchers, if not so much for those past soldiers, because it's the first evidence of Giardia duodenalis in Roman Britain.

Despite Vindolanda's bath complex, with its previously mentioned amenities, outbreaks occurred due to poor sanitary practices. Specifically, fecal contamination in food, water, and on the soldiers' hands helped spread these parasites throughout the fort and throughout time – samples collected from a fortification constructed in 85 CE also contained roundworm and whipworm.

As a result, parasite sufferers would have become severely ill from dehydration via chronic infections that could linger for weeks, "causing dramatic fatigue and weight loss." These conditions bred other severely deleterious intestinal pathogens, setting the scene for outbreaks of Salmonella and Shigella.

Written or uncovered evidence reveals many other types of Roman-reared infections. On one occasion, 10 soldiers were deemed unfit for duty due to conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye, which can occur when eyes come into contact with poop-laden fingers.

Interestingly, the parasite profile at Vindolanda is similar to that from other Roman military sites, including those in Austria, the Netherlands, and Scotland. One reason may be the more-limited, pork-heavy diet, as described in preserved texts.

In contrast, "Urban sites, such as London and York, had a more diverse parasite range, including fish and meat tapeworms."

So, for all the modern romanticism surrounding Roman hygiene, the history is often dirtier and more fecal-infested than imagined. It's also worth noting that nearly 2,000 years ago, Vindolanda sat at Rome's northwestern frontier, and frontier settlements often faced the harshest hardships – made all the harsher when its defenders had 30-centimeter (12-inch) roundworms snaking through their guts.

This research is published in Parasitology.