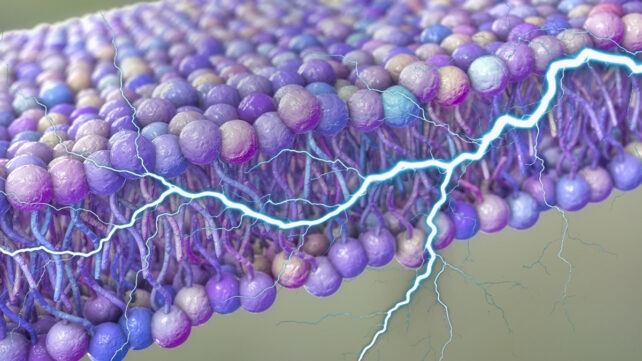

Our cells may literally ripple with electricity, acting as a hidden power supply that could help transport materials or even play a role in our body's communication.

Researchers from the University of Houston and Rutgers University in the US suggest small ripples in the fatty membranes surrounding our cells could generate enough voltage to serve as a direct source of energy for some biological processes.

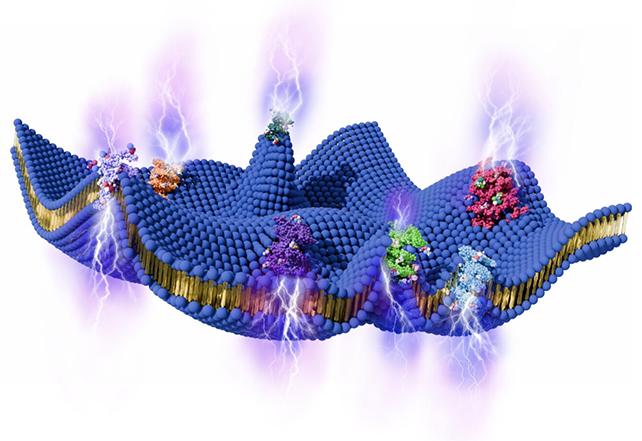

The fluctuations themselves have already been extensively studied and are known to be driven by the activity of embedded proteins and breakdown of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the primary means of transporting energy through cells.

The new study provides theoretical support for the possibility that membrane flutterings are strong enough and structured enough to create an electric charge that cells can use for some important tasks.

Related: Scientists Discover a Way to 'Recharge' Aging Human Cells

"Cells are not passive systems – they are driven by internal active processes such as protein activity and ATP consumption," write the researchers in their published paper.

"We show that these active fluctuations, when coupled with the universal electromechanical property of flexoelectricity, can generate transmembrane voltages and even drive ion transport."

Key to understanding the new model is the concept of flexoelectricity, which essentially describes the means by which a voltage can be produced between contrasting points of strain in a material.

Membranes are constantly bending as a result of heat fluctuating randomly through the cell. In theory, any voltage produced this way ought to cancel out in environments under equilibrium, making them useless as power sources.

The researchers reasoned that cells aren't in strict equilibrium, with activity inside the cell churning away to keep us alive. Whether it would be enough to turn a lipid membrane into an engine required a few detailed formulations.

As per the calculations done by the researchers, flexoelectricity could create an electrical difference between the inside and the outside of the cell: up to 90 millivolts, which is enough of a charge to get a neuron to fire.

The voltage produced could assist in the movement of ions, the charged atoms that are controlled by the flow of electricity and chemicals.

Membrane fluctuations may be enough to influence biological operations like muscle movement and sensory signals. The team estimated the charges emerge on a millisecond scale, suiting the timing of signals rippling through nerve cells.

"Our results reveal that activity can significantly amplify transmembrane voltage and polarization, suggesting a physical mechanism for energy harvesting and directed ion transport in living cells," write the researchers.

The findings could extend across groups of cells as well, helping to explain how cell membranes can be coordinated to generate larger-scale effects and tissues. Future studies can now test that this all works as expected inside the body.

These findings could have implications beyond living tissues: the researchers float the idea of using these same electricity-producing techniques to inform the design of artificial intelligence networks and synthetic materials based on nature.

"Investigating electromechanical dynamics in neuron networks may bridge molecular flexoelectricity and complex information processing, with implications for both understanding brain function and discovering bio-inspired computational materials," write the researchers.

The research has been published in PNAS Nexus.